Elusive graffiti artist and shoe designer INSA has been commissioned to produce a response to the recent Chris Ofili's 2010 exhibition at Tate Britain.

TateShots had a look around his London studio to see what he would come up with.

Insa:

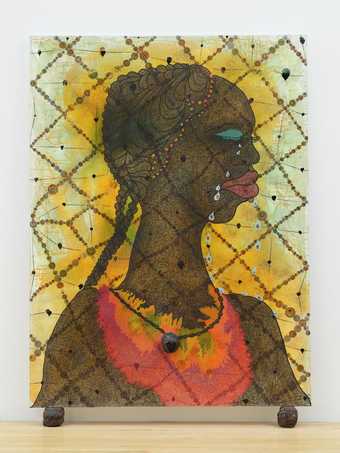

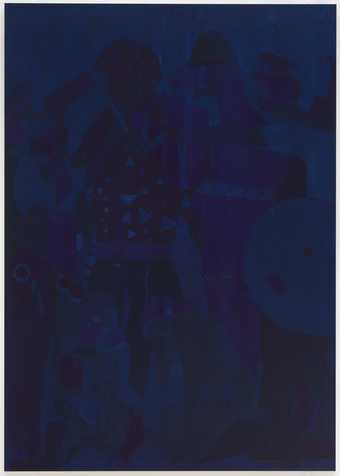

Yeah, I go by the name of Insa. I’m an artist. I used to be a free painter. This is my studio, and I’m currently working on a bit of work for a response to Chris Ofili’s Tate Retrospective. I’m building a light box. It’s going to have a rotating disc in it that gives this kind of kaleidoscopic light beams coming out.

The image of Dali that I’ve used is so iconic, it’s an old…colour from the early Nineties, of this figure, of this woman, in the crazy, smallest bikini you’ve ever seen, holding a big shotgun. I think to any pre-pubescent boy at the time, it became such a lodged image. You go on to think, who is she? Who is this woman? And you find out that it’s actually [inaudible 00:01:18] wife. She is the ultimate symbol, do you know what I mean, the ultimate trophy wife. It’s like, out of all hip or the kind of bullshit misogyny in Hip Hop, she’s the most iconic image. So to kind of juxtapose her with the worship of Mary – I like the idea, as I don’t have a figure to celebrate, I like the idea of putting her in the work as a beacon of the aspiration I meant to aspire to.

So it stands about six foot tall, has kind of a horrible goldy, gold frame. Tacky is not a very nice word, it’s too simple, but yeah, it’s got to have a certain charm.

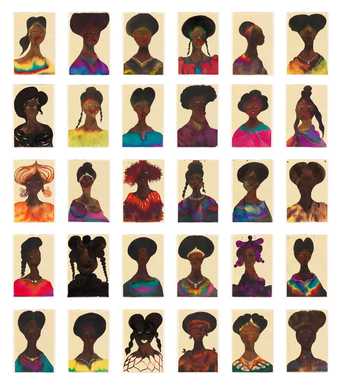

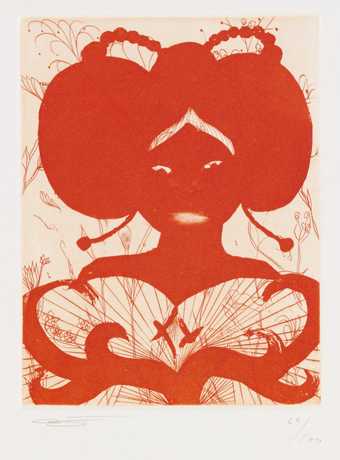

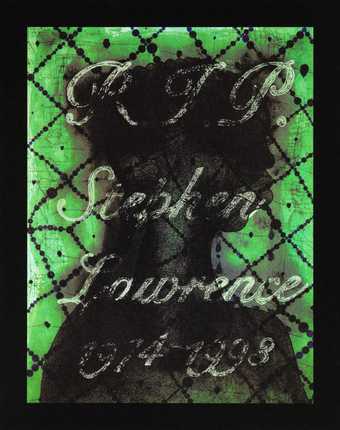

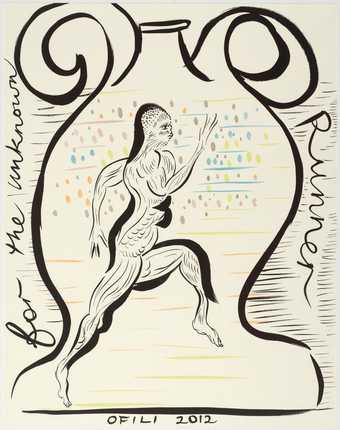

Yeah, I was really keen. I’ve been an admirer of Chris Ofili’s work for a long time since I first heard about him. Most people first heard about him back in the mid-Nineties. I think if I was to explain why I like his work, I think it’s very accessible, and I think I find a lot of fine art a bit pretentious and a bit exclusive, and not inviting for people to enjoy. But Chris Ofili’s work isn’t that. I think the use of humour in his work is really accessible, really enjoyable. And as well, it’s a combination of his fun that he’s had, but then also the kind of… he has still got beautiful paintings. I think there are different levels on which you can appreciate it.

I guess a lot of my work is very… uses a lot of objectified products or objectified women in the place of products, or what role this sexual objectification has in our consumer life.

I don’t want to show my face in this film because I have always worked under a kind of anonymity, removing myself from the work and allowing the work to represent itself. I want people to enjoy my work at whatever level they want to. Why I don’t like doing too many interviews, because I don’t want to dictate what people are meant to enjoy about my work. If it’s some kids, they are like, ‘Oh, I like Big Bums and Trainers,’ and that’s the level they’re going to get to enjoy the work. I mean, if they are enjoying it, I don’t want to dictate, ‘Well, actually, I’m critiquing your appreciation of acid trends.’

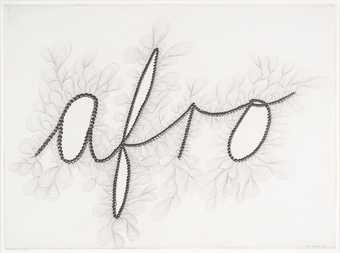

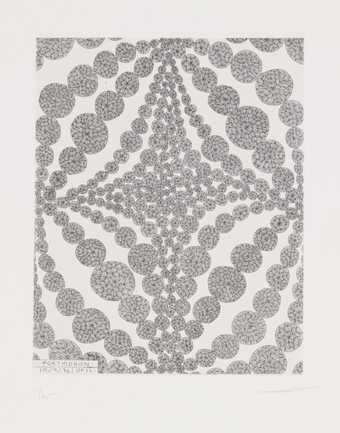

As well as doing the light box piece, I also, just because I do things with lots of high heels, and a lot of people that know my work, know Insa Heels as well. And I thought that a very obvious kind of, visually obvious response, would be me designing a pair of heels inspired by Chris’s work. So I’m building a pair of platform heels and using elephant dung as the actual basis of the platform. It’s ‘Anything goes, when it comes to ‘hoes’, with a silent S. So it’s, anything goes when it comes to shoes. This is a lyric from the Big Daddy Kane song, ‘Pimpin aint easy’. And one of Chris’s pieces is Pimpin aint easy, obviously referencing Big Daddy Kane, so I wanted to kind of paint the lyric before that, and I also quite like the idea that for Anything Goes about the shoes, even a pair of heels made of shit is still a desirable item.