In 1997, when I was 19 years old, my parents, both in their sixties, embarked on their first journey to Europe to encounter Western art. In the 1980s, during the post-Reform era in China, they learnt about Rodin, Michelangelo and Picasso only from the limited supply of foreign books in the library. These books expanded their horizons beyond the Russian school of the 1950s and the limitations of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, offering them new insights that informed their own artistic practices. Inspired by what they had learnt, they diligently introduced Western artistic concepts into the country, fusing them with Chinese culture, which in turn initiated a process of self-rediscovery in mainland China at a time when artistic judgement was still very conservative. It was almost twenty years later, in the latter days of their artistic career, that they were able to experience up close the original works that they had first studied from books.

Damien Hirst

Mother and Child (Divided) (exhibition copy 2007 (original 1993))

Tate

During their trip to Europe, my parents sent me a postcard from Germany featuring Damien Hirst’s Mother and Child Divided 1993 (Tate T12751). Immersed in formaldehyde, the dissected cow on the postcard struck me as an unforgettable image. My parents remarked in passing: ‘Nowadays, Western modern art is so avant-garde that even such an image can be called art!’ Although they were unable to appreciate Hirst’s work in the same way they could Rodin’s, the unusual and shocking image stirred my imagination, since it departed so completely from my own education and personal experience of visual art. While it is true that, by 1997, China’s ‘open-door’ policy had been in place for over twenty years and that Western culture and values had long been present in the East, before the internet became widely accessible, there was a delay in the transmission of information from the West, especially of news from the art world. In the art school where I was studying at the time, we knew little of modern art history beyond the Impressionists. My generation’s conception of contemporary Western art was confined to images of European cemeteries and sculptures shown to us on slides by our professors.

In 1999, while in my third year of university, I completed my first short film, Imbalance 257. It expresses my scepticism, my rebelliousness, my burning desire for art and my ambivalence about growing up, recalling the work of Damien Hirst that prompted me to articulate my unspeakable desires and impulses. My film conveys wildness, immediacy and passion.

The Scottish philosopher David Hume once remarked that despite the unwelcoming nature of sentiments such as sadness, fear and anxiety, one gains security and confidence from imagining and exploring the potential threats and uncertainties that underlie life. At the time I was making the film, the image of Damien Hirst’s sculpture inspired me greatly, as did the work of the so-called ‘young British artists’ (YBAs), who concerned themselves with fundamental human questions about the meaning of life, the existence of God and the limits of death.

In the same year, an exhibition of contemporary Chinese art opened in Beijing called Post Sense Sensibility. This title made direct reference to the infamous Sensation exhibition of work by YBAs from the Saatchi collection that travelled from the Royal Academy in London in 1997 to the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin and the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York. The exhibition’s curator Qiu Zhije remarked that a ‘post sense sensibility’ sought to excite the mind, to be unusual, and to stir the imagination. Curiosity, therefore, is what linked this exhibition of contemporary Chinese art with the work in Sensation.

I felt that Sensation and Post Sense Sensibility shared an affinity, with the latter focusing more on the vernacular language of local contemporary art. Like the YBAs, the Chinese artists exhibiting in Post Sense Sensibility sought to disclose the violence of globalisation: the threats of a monopolised economy, totalitarian rule, rigidity of artistic practice, and materialistic culture. It was precisely these social and political conditions that allowed Chinese contemporary art to blossom at the same time as the work of young British artists.

In the period before the Post Sense Sensibility exhibition, China was a divided and politically depressed society. Workers were laid off and state enterprises underwent tremendous reforms, accentuating the divisions between the rich and the poor. This social context, although different from that which gave rise to the work of the YBAs, resonated with their situation: ‘Plagued by the extremity of loneliness, fatigue and dubiousness towards life in a materialistic culture, young people [in Britain] began to doubt the Thatcher regime, resisting mainstream culture and protesting against the idea of commerce. Trainspotting, a global movie hit, epitomises the helplessness and anxiety experienced by the British society in face of daunting social issues’ (Amy Goya, blog post from Amy’s Mumbo Jumbo, 26 November 2006).

In 2000, a year after Post Sense Sensibility, an exhibition titled Infatuated With Injury was curated by Li Xianting. Participating artists made use of body parts (including corpses, flesh and blood) to express themselves in a collective manner. By the autumn of that same year, extremist work by a new generation of artists appeared in the Shanghai Biennale co-curated by Ai Weiwei and Feng Bo, titled Fuck Off. Li has remarked: ‘There is a premonition that a fearful thing exists in the society, an unbearable atmosphere or mood, constituting our inner uncertainties, fears, helplessness, anger and malaise. They crush our hearts and create pain in us, and it is only through artistic expression that we can give vent to these impulses’ (Li Xianting, ‘The Cult of Mutilation’, blog post, 24 March 2011).

Marc Quinn

No Visible Means of Escape IV (1996)

Tate

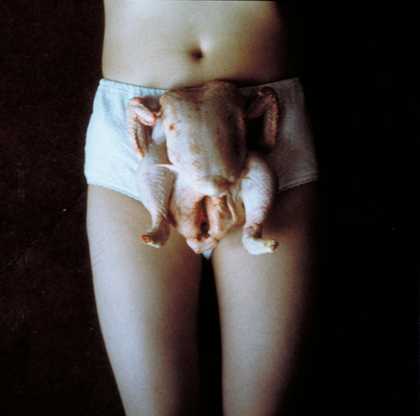

Sarah Lucas

Chicken Knickers (1997)

Tate

These artworks from mainland China can be linked to the deeper political turmoil of the period. They challenged the discrepancy in moral values between the traditions of the East and those of the West. This artistic tendency can also be understood as the Chinese equivalent of what the YBAs had been doing, only manifested in more extreme conditions. Whereas Marc Quinn chose to make a sculpture out of his own frozen blood, the Chinese artists Peng Yu and Sun Yuan pumped their blood into a dead baby’s mouth. Quinn’s sculpture No Visible Means of Escape IV 1996 (Tate T07238) presents a flayed replica of his own body suspended from the ceiling, while the controversial Chinese artist Zhu Yu dangled a severed human arm from the ceiling of a gallery in which images of him devouring infant corpses could also be seen. In response to Damien Hirst’s work Mother and Child Divided, the artist Xiao Yu made use of the corpses of rabbits, infants and birds to conjure a monstrous creature, soaked in a glass jar of chemical solution. Similarly, in my early film Chain Reaction 2000, I projected the birth of a pig head via a hideous operation, while Sarah Lucas’s photograph Chicken Knickers 1997 (Tate P78210) depicts the artist with a chicken positioned against her lower body. In an interview with a Western art magazine, the Chinese, Paris-based artist Huang Yong Ping expressed that ‘The concept of culture must be cleansed and spun over and over again’ (Philippe Piguet, ‘Huang Yong Ping, Cultural differences and négociation’, Flash Art International, no.32, July–August 1999, p.51). In other words, the West will shock the East, and the East will shock the West.

In April 2001, the Chinese Culture Ministry issued legislation to abolish violent or sexual performances and the display of artworks depicting animal abuse, self abuse, corpses, violence or pornography. As a result, the representation of violence eventually disappeared from contemporary art in China. Like the YBAs, struggling Chinese artists who had to work underground during this time would eventually get the opportunity to participate in the international art market.

In late 2006 the exhibition Aftershock – consisting of works by YBAs including Damien Hirst, Marc Quinn, Sam Taylor-Wood and Sarah Lucas – opened in China. Works by these artists have had a tremendous impact on Chinese art since the late 1990s, triggering the wild days of contemporary Chinese art. Nowadays, ‘YCAs’ (Young Chinese Artists) has become an analogous term, and the work of these artists has deservedly gained international attention.

Artists’ Perspectives provides a platform for international artists to reflect on individual works within Tate’s collection or a related theme. Their texts are published in English and in another language (or languages) of their choice, offering creative insights into Tate’s collection and art practice today for people in different parts of the world.

Chinese translation

- Chinese translation [PDF, 581KB]