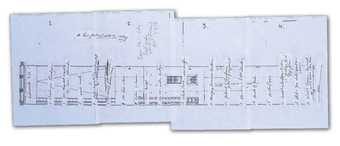

Plans for the Turbine Hall layout

Bruce Nauman is one of the most important artists of our time. Early in his career, he abandoned painting in favour of sculpture, performance, installation, film, video, photography and neon. This restless exploration of different media reflects a continual questioning and reinvention of his artistic practice. In the 1960s he was one of the pioneers of video art, making a series of groundbreaking videos in which he filmed himself in his studio performing various simple, often absurd, tasks. In subsequent videos he has often used actors to repeat a written text, with nuanced variations, so revealing the ambiguities and dead-ends of language. Sound has always been important to his artistic practice, sometimes as pure audio works, sometimes incorporated as an element in videos or large-scale architectural installations.

For Raw Materials, his sound installation for Tate Modern, Nauman has brought together 22 recordings of texts taken from earlier works that span almost 40 years of his career. Walking through the Turbine Hall, disembodied voices speak to you, or maybe just to themselves, in a variety of styles. There are stark texts like ‘OK OK OK’, which Nauman himself chants repeatedly until the phrase distorts and seems to morph into new words. Longer pieces such as ‘False Silence’ or ‘Consummate Mask of Rock’ are cryptic narratives describing psychological states that are at odds with the calm delivery of the voice. Somewhere in between is ‘Get Out of My Mind, Get Out of This Room’ in which Nauman repeats the statement as if on the edge of asphyxiation, his gasps and snarls building an atmosphere of claustrophobia and intimidation. There are statements that explore sentence construction, single words repeated over and over, stories that feed back into themselves and go nowhere. Throughout, the tone of voice, the inflection, and variations in rhythms dramatically shift meanings, from diplomatic to psychotic, pleading to bullying, anxiety to mockery.

Nauman’s interest in lexical systems shares something with the plays of Samuel Beckett or the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein. His fascination with deconstructing language and exposing its inherent ambiguities is paralleled by his approach to making art. In this work, the boundaries between sculpture, sound and language are blurred. The Turbine Hall is empty, but has paradoxically been filled with acoustic material based on the written word. It could be described as a play on the notion of ‘volume’, since as well as being a measurement of space and of sound, ‘volume’ suggests a text. It is precisely this sense of instability, where a single thing has many layers of meaning that often contradict one another, which Nauman’s work addresses.

The layering of fragments of previous works to create a new whole adds to this complexity. Some of the texts are audio components from videos or architectural installations, others are written texts from Nauman’s sculptures, prints or drawings. The diverse origins of the texts are significant, as Nauman has commented:

I think the range of material and presentations and intentions is important to the richness and density of the experience.

However, by isolating the texts and presenting them as sound recordings, Nauman admits:

Some texts are going to be reinforced, some will lose a lot compared with my original intentions, but I think that is okay. I’m just going to let that happen, however it happens. They’re out of context, so they become a whole new kind of experience … I am using these otherwise finished texts as raw material for a whole other idea … I am not as emotionally involved with the individual pieces as I would be if I were trying to re-install each one. I’m using this stuff in a kind of abstract way, or pretending it is abstract and allowing almost random associations to appear.

Rhythm has always been central to Nauman’s work. Some of the recordings include loops (‘OK OK OK’ or ‘No No No No – New Museum’) where single words are repeated over and over, with a different emphasis each time. Some of the loops are short and a pattern quickly emerges. Even background sounds that initially seem arbitrary evolve into percussive polyrhythms. Early in his career, Nauman was inspired by composer John Cage, who argued that chance occurrences and ambient sound can hold equal status with intentional composition. Other audio (‘Good Boy Bad Boy’ or ‘World Peace’) follows a pattern in which different words or phrases are conjugated like verbs, repeated in different voices to extract a variety of meanings. ‘100 Live and Die’ is a particularly musical work that creates a rhythm by attaching a word like ‘scream’ or ‘fail’ to the alternating endings ‘and live’ or ‘and die’. In each recitation the chorus of voices chanting the hundred phrases moves in and out of sync, in a way that recalls the modular music of composer Steve Reich. ‘Music plays a role in a lot of my work’, Nauman has said. ‘Even when there is no music’.

Sound responds to different spaces in particular ways and the Turbine Hall has a unique sonority. The low-level hum of generators can still be heard, a reminder of the building’s previous existence as a power station. This was influential in defining the project, as Nauman explains:

The first time I visited the Turbine Hall there was a group of Henry Moore sculptures on view. The first thought I had was to use the overhead cranes to fly them around the space… I think that what edged me toward an audio environment was the turbine drone and how it varied as I moved from place to place.

Nauman decided against placing the recordings in a thematic or chronological order. He says:

I started with the idea of using ‘Thank You Thank You’ at the entrance, but after that the arrangement was quite intuitive, and based more on the texture and intensity of the relationships than narrative structure. I do feel that the last piece in the room – ‘World Peace’ – is in an appropriate place, provides a resting place, but of course people will have to walk through the space to leave the museum proper.

In ‘World Peace’ we hear a man and woman recite a series of simple phrases around the verbs ‘talk’ and ‘listen’, such as ‘I’ll talk/ They’ll listen’ and ‘You’ll listen to us/ We’ll talk to you.’ In each instance, the statement is reversed in the following line before moving on to the next in the sequence. The title can be taken as a wry comment on global-political misunderstanding. With an economy of means, Nauman simultaneously represents the simplicity and complexity of communication.

Ben Borthwick, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern