There is some simplicity in which there is profound wisdom. Such is the art of Bernd and Hilla Becher. For more than 40 years they have been making pictures in a systematic and unerring manner. From the beginning, their work has been scorned by curators of photography for being ‘inartistic’. It makes no difference to the Bechers; they have never looked to art photographers for inspiration.

Years later, and the Bechers have become the guiding light behind the so-called objective school of photography, and their students are achieving prominent positions which were previously unimaginable for photographers in the art world, but there is still much muttering of dissent from the photographic community. How can such matter-of-fact photography be art? The answer lies in one simple verb: look. For looking is the heart of the Bechers’ work, and is the reason why they use photography as their medium, for one definition of photography is a long look.

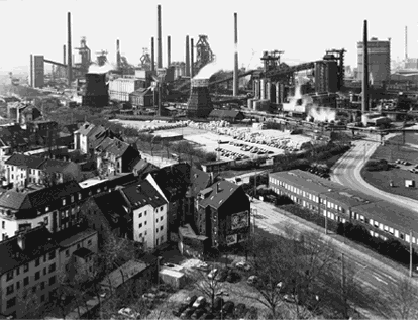

Bernd Becher was born in 1931 in the Ruhr valley, into a family that worked in the region’s steel and mining industries. His home town, Siegen, sprawled around a blast furnace and, from childhood onwards, he was fascinated with industrial structures.

In his youth, he found a photograph of an ironworks in a gazette of local businesses. Taken by a commercial photographer, and humbly reproduced on poor-quality paper, Grube Eisernhardter Tiefbau is the kind of picture that many people would find unremarkable. But for Bernd, this straightforward, workmanlike photograph of the foundry was wonderful. Some years later, by which time he had studied illustration at art college, Bernd returned to draw the ironworks but, before he could finish, the demolition of the site had begun. This was in 1957, a time when many of the foundries around Siegen were being decommissioned. In order to have a reference of the structure before it was gone, he took a series of photographs with a 35mm camera. His intention was to finish the drawings in his studio, but he found that the photographs offered a much more vivid depiction of the subject than he could achieve by hand.

Abandoning his drawing, Bernd tried to make a collage from the photographs, but he soon rejected this idea. Although the images were full of visual information about the structures, individually they held only a partial record. His next step was to splice the photographic prints together to make a composite picture. It was an advance on the collages, but it was still an imperfect solution.

Then he met Hilla Wobeser, his future wife. She not only shared his interest in the industrial landscape, but was also a technically accomplished photographer. They began a creative partnership that has taken them on a lifetime’s journey across the industrialised world. Together, they have recorded a magnificent history of the fast-disappearing modern archaeology of the West’s industrialisation. But they have contributed so much more – through their example and their work they have restored photography to its rightful place as great art. This is neither an idle boast about them, nor an exaggerated claim made purely for the merits of the medium. By using photography to look long and hard – neither minimising some appearances, nor maximising others – they have shown how a calm, clear and unconditional view of life is so very wonderful.

Hilla was born in Potsdam in 1934. Her mother had been a photographer and taught Hilla the basic skills. After leaving school, Hilla became the apprentice of Walter Eichgrun, whose family had been, for three generations, photographers to the Prussian court at Sans Souci. Deeply traditional, Eichgrun taught her the fundamental techniques of his conservative approach to photography. He practised what Hilla calls ‘direct, descriptive photography… clear, clean images – with a complete tonal range, with appropriate depths – devoted to the subject’. This was the application of photography that Bernd sought for his pictures of industrial structures, one of the properties of the medium he had seen in the earlier picture of the ironworks.

Bernd and Hilla met at the Troost advertising agency in 1957, where he was working to support himself as a student at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. The next year, Hilla enrolled at the Academy to study photography. There was no photography course, but some of the teachers were interested, so Hilla was given responsibility for ordering the necessary equipment. Resources were scarce, but it gave the Bechers the means to use the appropriate camera and darkroom facilities.

They immediately moved up from a Rolleiflex to a plate camera. It was, in essence, the same equipment as Walter Eichgrun had used and, apart from a few innovative modifications, the same type of camera that the great landscape photographers of the 19th century had employed. Bernd and Hilla followed exactly the same approach, too. This was not in order to emphasise a tradition, or to reflect on the past; it was simply to use a camera to take the clearest pictures possible. This quality was largely discarded when art photographers thought that their pictures needed effects – soft focus, high contrast and so on – for the resulting image to be defined as art. It was a movement that produced decades of ridiculous photographs and almost succeeded in downgrading the simplest and the most studious use of a camera.

Just as the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) used a camera obscura to trace the lines of ‘normal’ perspective, so did the pioneering photographers of the 19th century discover, by eliminating optical distortions and capturing detail, how to create realistic photographs. Among the finest of these was the American Carleton Watkins (1829– 1916).

Watkins’ first landscape commission – a photographic record of a quicksilver mine used as evidence to settle a land claim – required clarity and a sense of objectivity. It was a ‘record photograph’. The detail Watkins achieved with his landscapes was fundamental to their marvel, but it was his sense of composition and wonder that elevated them to high art. However, none of this would have been possible had he not been able to create pictures that had no distortion and were brimming with information.

The photograph of the ironworks at Eisern that inspired Bernd was a record picture, too. Record photographers are the unsung heroes of the history of photography. They are the anonymous commercial photographers who were commissioned to record both great and everyday industrial and civic projects, from the construction of canals to the blooming of floral clocks. Most industries would maintain a photographic record of their operations, partly as a technical archive and partly for commemorative or promotional purposes.

When Bernd began photographing around Siegen, he came across the record-picture archives of a number of steelworks. These formed the photographic references for his work. While many would perceive this type of photograph as 19th-century in style, the Bechers, quite rightly, regarded it as a timeless and perfectly practical use of the medium. It also held a significant philosophical implication.

The Bechers’ purpose has always been to make the clearest possible photographs of industrial structures. They are not interested in making euphemistic, socio-romantic pictures glorifying industry, nor doom-laden spectacles showing its costs and dangers. Equally, they have nothing in common with photographers who seek to make pleasing modernist abstractions, treating the structures as decorative shapes divorced from their function.

The Bechers’ goal is to create photographs that are concentrated on the structures themselves and not qualified by subjective interpretations. To them, these structures are the ‘architecture of engineers’ and their pictures should be seen as the photography of engineers – that is, record pictures.

So, in 1959, the Bechers drove around the Ruhr in a van photographing blast furnaces, winding towers, gas tanks, cooling towers, water towers, lime kilns and framework houses. They would use ladders and scaffolding to achieve clear vantage points from which to make their pictures. Like technical drawings, these would feature front and side elevations.

At that time colour film was not a practical consideration; black-and-white was the only viable choice. Photographing on overcast days, when the effects of shadows are negligible, gives their pictures great clarity. The Bechers endeavour to use similar lighting conditions, so all of their prints have roughly the same range of black, grey and white tones. This allows the photographs to be compared with one another without extraneous differences – dramatic skies or deep shadows – distracting from the subject matter. It also means that each individual picture is as faithful and accurate a record of the structure as possible.

The Bechers are fascinated by the idiosyncratic appearance of each structure. The mass-produced, design-conscious assemblies devised by architects with an eye on appearance do not appeal as much as those with a mindfulness of function. What interests the Bechers are constructions made by engineers whose plans are pragmatic, where function dictates the form, rather than, as is increasingly the case, the other way round. In the words of Bernd: ‘There is a form of architecture that consists in essence of apparatus, that has nothing to do with design, and nothing to do with architecture either. They are engineering constructions with their own aesthetic.’

Their fascination is rooted in an understanding of the structures. The Bechers are the first to acknowledge the primarily functional role of the constructions, that their existence is justified solely by their industrial performance, and that once this has been superseded the structures will be modified or demolished. They liken the way a blast furnace develops over time, as furnaces and pipework are added, to the organic but apparently chaotic growth of a medieval city. This purpose-led rationale is what attracts them. They refer to some of the structures as ‘nomadic architecture’. Once they photographed a blast furnace that was being dismantled by Chinese workers in Luxembourg, who then had to reassemble it in China.

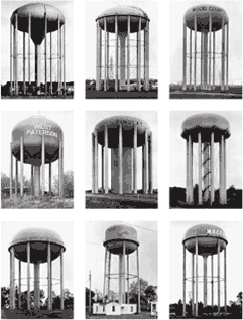

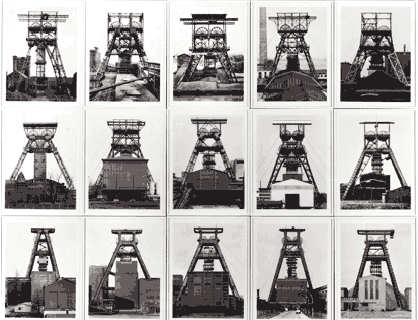

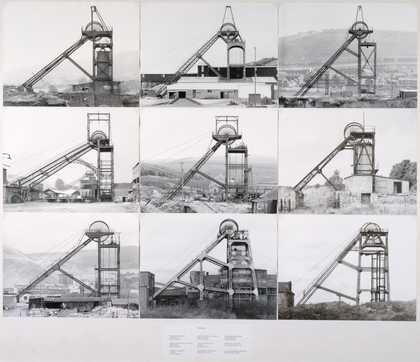

By placing photographs of similar subjects alongside each other, the individual differences emerge, making the fine details in each picture more noticeable, more distinct. Drawing on this, they began exhibiting the pictures as typologies; by the early 1960s they showed their work only in typological groups. Typically, a piece of work would comprise four small prints of, for example, water towers, adjacent to a larger print of one of the four. They would not supply prints of individual pictures; the typology was the work. Later, their typologies contained prints of equal size, measuring 30 cm by 40 cm. It could be three rows of five prints, a grid of nine or, in one case, 28 blast furnaces in three rows; a symphony of industrial structures.

The Bechers’ pictures do not have to be viewed in typologies in order to make sense, as they have validity as individual images. The typology has been developed for two reasons. First, by amassing such a detailed survey of industrial structures they are revealing sets and subsets, much like 19th-century zoologists did. With water towers, for example, there are round steel ones with conical tops, like hats, and semi-circular ones. Others are circular with sloping roofs, or without roofs, or on steel derricks, or brick towers, and so on. The more fine the differences, the better they are illustrated by the typology.

Second, the typology used by the Bechers emphasises the rewards of close scrutiny, and it is this that makes each and every one of their pictures fascinating. By presenting 15 water towers in a grid, the first effect is an imposing mass of industrial structures. You must stand back in order to take them all in as a group, but to look closer at an individual picture it is necessary to draw nearer.

Up close, only one tower is visible at a time. Isolated in pristine, black-and-white definition, this everyday object is revealed as an ‘anonymous sculpture’, an unostentatious but fabulous creation by mankind. To compare it with the others is to stand back again, and from here the impulse is to step up and examine another. Just as the beauty of the individual structure (for that is what they are) is there to see, so together as a typology they are a thrilling spectacle.

Apart from presenting them as typologies, the Bechers produced a series of monographs covering a range of industrial structures. In these finely printed books, the pictures are published one to a page. They are like portraits and the devotional aspect of their work becomes apparent. Photography, like film, has two specific properties. The first is that the photograph will record far more than the eye could see at the time of exposure. It traps details so finely on the negative that it would take the naked eye a long time to uncover the same amount of information. As with a view from a window, one can look and look and look, always seeing more.

Secondly, and more subtly, a photograph reflects the way the photographer engages with the subject. Take a picture of something you hate and it shows. Likewise, take a picture of something you find wonderful, and a sense of this wonder will be apparent. This is the double-edged sword of photography – and the reason why it should be treated with respect. Much like a lie detector, if you try to make a photograph to deliberately solicit a certain response then the manipulation, however subtle, will be transparent.

There is a wisdom and honour in the Bechers’ work which frees them from imposing a conditional reading upon the viewer. The wisdom is the methodology they recognise in the ‘neutral’ depiction of record photography. The honour stems from a principle about not imposing their ideas on other people.

Hilla and Bernd both grew up under Adolf Hitler. They saw how he corrupted German art to promote his propaganda. This was particularly pertinent to photography, and it remained tainted after the war; witness the grim examples of Leni Riefensthal’s glorifying images of Nazis and the pseudo-scientific eugenic portrait studies that were published to defend anti-semitism and supremacism. This is why the legacy of August Sander (1876–1964), whose neutral approach to portraiture was damned by the Nazis, is so precious in Germany. It is also why the Bechers’ continuing example is extremely important.

Between 1976 and 1996, Bernd was the professor of photography at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. During this period, his teachings inspired a generation of German artists who were part of the objective school, whose luminaries include Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky, Candida Hoffer, Thomas Ruff and Axel Hütte. All of their highly successful careers have been founded on work that faithfully follows the principles that the Bechers adopted.

Because photography has, for so long, been used for commercial reasons, notably in advertising, people are accustomed to absorbing manipulative images, and have come to expect – or even rely on – a conditional presentation. Take away this interpretative control and the viewer is left free, which is unnerving if one is not used to it. This is why some regard the Bechers’ photographs as ‘cold’. There is no editorial, no soundtrack, no suggestions nor judgments. You are left to your own devices.

Of course, their motivations are not invisible, nor their presence unfelt. What does it mean when something ‘rings true’? How is it that one can sense the sincerity in another’s words? Perhaps this lies in the realm of intuition, not explanation. To analyse art is not necessarily to experience it. Sometimes, by focusing on a deliberation of it, one limits the engagement to a cerebral encounter. In the West particularly, we use explanations to try to control the unknown, to make uncertainties certain. Maybe there is a wisdom we have that is not learnt but is within us. Far better to look rather than puzzle, and to open one’s senses to what is there.

Here lies the wonder in the Bechers’ photographs. They are like rounding a hill and seeing a view spread out before you. In Cwmcynon Colliery, Mountain Ash, South Wales, 1966, a minehead stands above lines of terraced houses in the village. The giant pair of wheels on top of the single-tier steel headframe is an engineer’s structure. A device to do a job, not to win design awards. You could not dream up such structures, neither could you invent, say, your grandparents’ kitchen. These things arise from the conditions in which they are used.

They are the lines on the face of the world. The photographs are portraits of our history. And when the structures have been demolished and grassed over, as though they were never there, the pictures remain.

Industrial Landscapes by Bernd and Hilla Becher is published this month by MIT Press and Schirmer/Mosel Verlag at 40. For further information on books by Bernd and Hilla Becher, visit www.schirmer-mosel.de. The Erasmus Prize, worth €210,000, is awarded annually for outstanding contribution to European culture and society. An exhibition of the Bechers’ work to mark the award is at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam from 14 September to 1 December 2002.