Jane Burton

The Kiss by Auguste Rodin is one of the most popular works in Tate’s collection, and today you’d hardly consider it shocking or provocative.

But it hasn’t always been this way. When it was first shown in this country in 1914, its erotic subject matter caused a scandal. It had to be covered with a tarpaulin and hidden away in a stable block.

The story behind the creation of The Kiss and how it came to enter Tate’s collection is a fascinating one.

Rodin was one of the pre-eminent sculptors of the modern era. He challenged the academic traditions of late nineteenth-century art and took sculpture in a new direction.

In 1880, at the age of 40, Rodin was commissioned to make a monumental bronze doorway for a new museum in Paris. He called them The Gates of Hell. Rodin’s inspiration was Dante’s Inferno, characters from which Rodin modelled as reliefs on the doors.

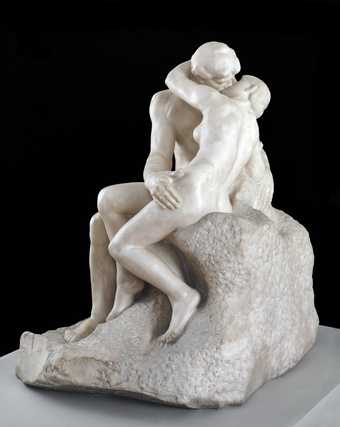

They included the tragic lovers Paolo and Francesca who later became the couple in The Kiss. Paolo was the brother of Francesca’s husband, and Dante tells how their love was first kindled when they sat together and read the story of Lancelot and Guinevere. But in their moment of passion they were discovered by Francesca’s husband, and murdered. If you look at The Kiss, you can just make out in Paolo’s hand the book they were reading, before they succumbed to their passion.

Rodin eventually decided to detach the figures and make them into an independent sculpture. There are some wonderful early studies for The Kiss, including a small almost abstract, terracotta model in which he rehearses the pose as if trying to distil the very essence of forbidden passion.

The Tate’s Kiss is one of three larger than life-size marble sculptures Rodin produced on the subject. The first was commissioned by the French government in 1888. Ten years later, when Rodin finally finished the sculpture, it went on show in Paris, where it was considered a great success.

One person who fell in love with The Kiss in Paris was British artist William Rothenstein. He persuaded a collector friend of his to commission the version that we find today in the Tate.

Rothenstein’s friend was the eccentric American collector Edward Perry Warren. Warren lived in Lewes House in Sussex with his lover John Marshall and together they entertained a brotherhood of artists, dealers and scholars.

Warren saw Rodin as the modern inheritor of the classical Greek tradition. This may explain a rather unorthodox letter to Rodin in which he asks that in his version of The Kiss, the man’s genitals be clearly sculpted in the Greek tradition, rather than modestly hidden.

Warren paid Rodin 20,000 French francs for the sculpture, a large sum at the time, but when The Kiss finally arrived here in 1904, it was put into the stables. It isn’t known whether this was because it was too big for the house, or simply because it failed to live up to Warren’s expectations.

In 1914 Warren lent it to Lewes Town Council for display in the Town Hall. But its amorous subject matter scandalised local residents. Shortly afterwards, soldiers were billeted in the Town Hall at the start of the war, and it was hastily draped in a tarpaulin, lest it overexcite the troops.

After Warren’s death in 1928 The Kiss was put up for auction but failed to reach its asking price.

In 1952, the Tate launched a public appeal to buy the sculpture for the nation, for the bargain price of £7,500. ‘A kiss that’s worth £7,500’ said the French cartoonist in Dimanche. ‘That’s expensive for a kiss – Yes, but it lasts a long time’.

Over the years other artists have paid homage to The Kiss. In this etching Marcel Duchamp outlines the lovers, but in typically subversive spirit. A slight change to the position of the man’s hand suggests a far more intimate caress.

More recently British artist Cornelia Parker tied it up in string, an act of bondage that perhaps captures the spirit of Rodin’s original – both its erotic power and the pain of love.