Sandra Jean Pierre: You are listening to Tate Podcast, the Art of Persona with me, Sandra Jean Pierre. This is a series exploring the human stories behind art.

The. Art. Of.

SJP: So we’re ringing but it’s a bit locked. I think this is broken. Oh, it’s open, actually.

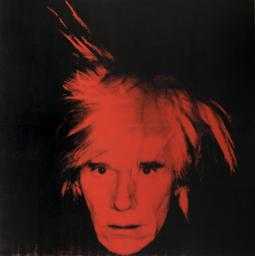

Bob Colacello: You know Andy was just Andy. He was one of a kind.

SJP: Persona can be defined as the aspect of someone’s character that is presented to or perceived by others.

BC: I mean with the press he always just gave these very cryptic, deliberately misleading answers. In one article he said he was born in Newport, Rhode Island and another it was Philadelphia and a third it was McKeesport, Pennsylvania. He never said Pittsburgh, where he was really born.

SJP: This is Bob Colacello. He was a colleague and good friend of Andy Warhol. Warhol was the leading figure of pop art but also a filmmaker, producer, magazine and ad illustrator. He reimagined what being an artist and a star could be.

BC: I think he understood that mystery keeps the press coming back, so the more you throw them off the track, the better it is in a way.

SJP: For me, Warhol’s public persona was indistinguishable from his art. Even the people close to him could not define him.

BC: He was very endearing but he was also calculated to a degree. I mean it was hard to know.

SJP: I am a music producer and researcher. I run the project Marasa which explores how sound and radio can be mediums to build new ways of listening. As someone that had to use my voice to introduce ideas, I have always been intrigued by persona.

BC: I know that Andy was factually and, you know, biographically, Andy was an outsider.

SJP: I was recently sitting outside a coffee shop watching people go by and I noticed so many different ways of performing little daily acts. I want to learn about what persona means for artists today, how it can be used in different ways, how celebratory, therapeutic, protective, and all the things in between.

Lewis G. Burton: I had done a couple of interviews where it’s been a joke between myself and the collaborator where I’ll just sit there and not say anything, you know, thinking like, oh, should we just do this today, you know, it’ll be fun.

RJU: I’ve emulated Venus and Serena Williams in the best way I can, I guess.

Holly Beasley-Garrigan: Who even am I? What is my authentic self? I don’t know.

SJP: This is The Art of Persona.

LGB: Hi.

SJP: Hi, hello.

LGB: Nice to meet you, I’m Lewis.

SJP: Nice to meet you. Nice to meet you, come in.

The first artist I met was Lewis G. Burton. Yes. Lewis is a London-based DJ, performer and activist. They co-founded LGBTQ+ performance art platform and techno rave INFERNO, which gives space to their community to express themselves and be mentored. They do not describe themselves as a drag artist but drag is just one part of their practice.

LGB: Do you want a peppermint tea or a green tea?

SJP: Peppermint would be great, thank you.

LGB: Yes. So for me you have to look back at the history of drag and what is drag. And drag, in its quintessential essence, is performativity. I think recently it’s been confused a lot with thinking of men dressing as women. Being drag is anything, so you can be in drag wearing your suit for your first job interview for a new job and you’re in drag because you’re presenting a version of yourself that you want other people to see. You can be in drag when you’re at your friend’s wedding and you’re wearing a luxurious evening gown or something and you’re performing your class and you’re performing your style and your identity to other people.

Servant of pain, queer messiah, divine almighty, celestial being, hermaphrodite

LGB: I think with drag there can be this idea of playing a character. I mean, certainly, people can be in drag playing a character but we’re all dragging up to a certain extent to show a version of ourselves or a version of what other people want to see from you to fit a certain role within society. I look back at my history as a queer person and a lot of that is from drag culture and I take inspiration from that but also drag allows me a safe space to perform the heightened version of my femininity. Because drag is so accessible now to the mainstream, they see that and people want to put you in a box as a drag queen but actually I’m just a queer person who knows my history and is paying homage to that.

SJP: Yes, I see. That makes sense.

Rosa Johan Uddoh: So I guess I’m interested particularly in characters that make up what we think of as black culture or British culture. I’m interested in how these particular characters come to be examples or symbols of particular identities.

SJP: Rosa Johan Uddoh has participated in Marasa, the project I run. I thought she would be great to talk to because she’s a disciplinary artist whose practice is all about unpacking different versions of herself. I visited her studio in Poplar.

RJU: I guess fundamentally I’m interested in how we emulate certain figures that are in popular media so people like Moira Stuart or Serena and Venus Williams, Meghan Markle, Hercule Poirot. All of these are figures that are perhaps in some ways presented as role models for people who are black or British and also what people who are not black or British think of when they think of foreigners or people from the colonies or stuff like that. So I’m quite interested in using performance to unpack these characters.

The serve, aligning the feet. On the 9th July 2016, my little sister’s birthday, Serena Williams won the Wimbledon final, gaining her 22nd Grand Slam title. The semi-final had seen a showdown between Serena…

RJU: I think performance is a very physical act so sometimes there’s things that you can reach a better understanding of things through embodying a person. There are things that your body will realise through you mimicking that person or trying to walk behind that person that you wouldn’t have been able to get to just through thinking.

Holding the ball, fingers in formation.

RJU: Being a person who’s black and a performance artist is so interesting because the sphere of performance is actually a place where, you know, compared to other fields, we do actually have a lot of, quote, unquote, role models. So all of the characters that I’m looking at I do consider performers, whether they be very subtly performing or more overtly performing. I do a lot of work based off Diana Ross and the Supremes so that’s one very recognisable type of performance which is musical but also thinking about Venus and Serena as sports performers. Because that is a sphere that black people have historically been allowed to excel in, now when you come at that with performance art, using performance art as a critical tool to unpack exactly what was going on there, unpack the power relations and see what I can now rescue for myself.

JK: My name’s JK, I’m one half of Scary Things.

DJ Bempah: My name’s DJ Bempah. I’m a half of Scary Things. DJ for NTS Radio 67.

SJP: While working as a radio producer at NTS Radio, I came across Scary Things. It’s a one-stop-shop that you can go to to find out everything that is going on in the underground and mainstream UK and American rap scenes. I met with them to learn more about personas in the UK Drill scene. I wanted to know if younger rappers were emulating older rappers’ personas when they started their careers and if, once they got more experience, they could just be themselves.

JK: That just comes down to the lack of scene that we have. It’s because the only things that the younger ones can actually look up to is the past five years, I would probably say, because that’s when money properly started getting made in the scene. So it’s like they’re going to have to emulate the way those guys did it.

DJB: It’s like this is actually the first time we’re actually seeing any of this happen in the UK scene.

JK: You know what I’m saying, forever.

DJB: There was never a UK scene anyway for like the urban scene. There was So Solid Crew and Dizzee Rascal and a couple of guys.

SJP: What is Scary Things?

JK: Scary Things is where to come to because you never know what’s going to happen in Scary Things, you know, change is scary, we are the change so, you know, stick with us.

SJP: Okay.

JK: We’ll take you through. We’ll take you through.

SJP: Have you been shocked in the past by the difference between the persona of an artist on stage and through a video clip and when you actually meet him?

JK: Oh, yes, definitely and that’s, kind of, where Scary Things started. It’s just like that like where you see a guy’s music and you see him with a mask and he’s talking this and talking that, what the media might represent him as and it’s like you actually meet him and it’s like, oh, I thought you were a scary guy.

DJB: Exactly.

JK: So, yes, we always see the differences. We always see people come in and you’re not the type of person you are.

DJB: Exactly.

JK: You might be some boisterous character and you’re really quiet on the mic.

Hey, there, are you 16 to 25? Want £5 tickets to Tate exhibitions, free events, creative opportunities and special discounts? Join Tate Collective.

Holly Beasley-Garrigan: Is everyone here? Is anyone here? Hello?

Audience: Hi.

HBG: Yes, okay, so how many people are like on the front row? Is it like full because I don’t know if I want to come out unless it’s…?

Yes, it’s pretty full.

Oh, good, alright, so could somebody on the left…

Part of the backdrop, I guess, of the show is a childhood duvet cover which is, kind of, a knock off Groovy Chick duvet cover that’s quite recognisable if you grew up in the ’90s.

Lauren. Lauren, yes. Lauren, how tall are you?

Then hung next to that is a dress which is my old prom dress from when I was 16 and then an image projected on an overhead projector onto the dress which is a picture of my face when I was a teenager and I look really different to how I look now. It was part of me trying to reconnect with an old version of myself, almost like a ghost of me.

That picture sums up the estate in the ’90s. That is what every girl looked like.

SJP: Holly Beasley-Garrigan is a performance maker, performer and movement director with a background crossing theatre, dance, music and light art.

HBG: Yes, it’s just a bit of me that I try to forget about.

SJP: Last year, I went to see her show Opal Fruits. During a full hour she’s alone on stage. Opal Fruits is about working class women and the trouble with ’90s nostalgia.

HBG: Then what else?

Reebok classics.

Yes, Reebok classics…

HBG: It weaves stories from four generations of women growing up on the same council estate in south London.

…and the gold…that’s where you’d get it from.

What phone was it?

A 3210.

That’s right.

What music were you listening to?

Garage. Garage. Garage.

HBG: So I, sort of, approached it initially with a layer of removal, I think and I just thought that I’d wear some stupid outfits and play some silly music and reminisce about the ’90s and this council estate where I grew up. It wouldn’t particularly be that person though I think because at the time, I was quite removed from it as a person. I feel like I’d suppressed that part of my identity so much at the time and then through making it, it became super, super, super personal.

SJP: So I’m wondering if sometimes you adopt a different persona when you’re on stage or do you just like allow all your vulnerabilities to show?

HBG: I think it’s impossible to be your authentic self on stage.

SJP: Okay.

HBG: It’s this weird thing, I think, being a performer, isn’t it? It’s you’re, sort of, going round and round in circles of, I can only ever be me, that’s all I can ever be but this version of me is a, kind of, performed version of me. I’m quite interested in this idea of playing yourself on stage and finding those different versions of yourself. I enjoy that. It’s fun for me. It’s, kind of, a bit mischievous.

SJP: A similar question applies to rappers in the music scene. What is the personal and what is the performed? How do you know when to stop blurring the lines?

DJB: The whole drill persona that everyone puts on anywhere, it’s like not everyone does live that horrid gritty life, like the pain and rappers rap about. Some will say, yeah, I slept the cold nights on the kitchen floor but they really weren’t sleeping those cold nights on the kitchen floor.

SJP: Yes, of course.

DJB: You have to say that so everyone feels like, oh, yeah, so the man that slept on the kitchen floor feels like, he feels my pain. I get it. I feel like he’s relatable. So people put on all types of personas. That’s what helps a lot of guys when they put a mask on because you can be whoever you want to be.

JK: You could be the biggest killer, you could be the biggest lady-man, you could be the biggest pusher man, you could be anything.

DJB: You could be anything. Anything.

JK: Anything.

DJB: It’s one of those ones where you get found out because you didn’t live that life then obviously people aren’t going to like that because you’ll feel lied to at the end of the day because don’t talk like you lived my pain and you haven’t lived my pain. Real life experiences, bro. This isn’t pop where there’s like four, five writers on your track. I need to see your name and no-one else. I need to know that, yeah, you wrote this and like, come, you can’t go to a party and spit someone else’s rhymes.

JK: It’s true.

DJB: What’s that?

JK: It’s true.

DJB: Like what?

JK: Even the first rap song ever made… The first rap song that was actually commercially successful, that’s one of the lines in there, you don’t ever let another rapper steal your rhymes, you know what I’m saying.

DJB: No way.

JK: So if like the mask, kind of, excludes you from having to own up to any of said things you’re rapping.

DJB: Yes.

LGB: When I moved to London I came here and I was dressing very extremely, wearing over-the-top makeup and big outfits and huge platforms and I jumped into the deep end of being able to explore what my queerness should be like. Also at the same time because I’d not really dealt with those feelings of shame and guilt and these traumas that come with repressing yourself for so long and really not learning to like the person that I was, it was a journey of me experimenting with my identity and performing almost as a way of self-therapy to come to terms with who I was and really learn to like the person I was and now love the person that I am. So I spent a lot of my early practice being extra ugly because this is how I felt on the inside. It was me being like this is how you’re making me feel so I’m going to show you how you make me feel. It was a really good exercise for me to learn to see real beauty within that ugliness.

I’m from an old mining village on the outskirts of Newcastle. It’s very working class there and very traditional and almost a bit conservative in their values when it comes to gender norms so it was very difficult for me. I would only go home for very short bursts of time and there was a very clear separation between my old self and the person that the people around me, my loved ones, my family, my friends, expected from me and actually the person that I am. I’m older now. I’ve had very nice chats with my family and I can dress the way I want to dress. I still obviously tone it down a tiny bit but not that much that it’s hurting or affecting me. I get to still be myself, can still wear some fabulous dresses. It was really nice, actually, last year I had a gig in Newcastle for the first time and my mam got to see me in all of my regalia. She told me I looked beautiful and it was a very nice moment for me.

SJP: It seems like they have found therapeutic benefits to playing with their personas to performance. Could it be about self-discovery?

RJU: I guess I’m just interested in all of these characters and how they have an effect on self-formation. For me, I guess almost it’s a, kind of, therapy to understand why I see myself in a certain way, why I’ve taken certain paths through putting myself literally in their shoes, trying to learn from them but also trying to undo this very immediate visceral pull that I feel to identify with them.

SJP: Okay, I see.

RJU: I feel like that’s so automatic. It’s almost like an infatuation with certain people who represent you. Especially as a black woman, it’s quite rare that you’ll find someone who you really identify with in the public eye so when you do it’s often almost like a love relationship.

SJP: Yes, specifically when it’s like BBC News, the TV and you see that figure every single day at the same time.

RJU: Exactly, exactly, exactly.

SJP: Working towards self-esteem is essential even more when the way we present ourselves to the world can differ from how we are perceived by others because of class, race or gender.

RJU: Higher education was really, really difficult actually, drama school particularly. I think I was pretty much the only person in my class who hadn’t been to private school. I changed my accent while I was there just through going to voice classes and being told to speak a certain way and where to place your tongue in your mouth and what sounds are good and what sounds are bad. It was really difficult to be different in that environment and to not really have anyone else around who really understood what that was like. I think that changed me quite a lot that I’m still just now, really, sort of trying to reconcile with, I think.

I cannot eat these eggs. They are totally different sizes.

RJU: Poirot might be like a strange character to include in the line-up of other characters that I look at but, for me, he’s very important because he’s one of the first representations of an outsider on TV that I saw. He’s a refugee. Everyone is very xenophobic towards him. He dabbles in respectability politics. He wants to be liked. He wants to obey the very British upper class conventions of the aristocracy that he hangs out with and he’s also hugely popular. So I made that work because I was interested in him as a representation of a foreigner but also, in a way, as a token and someone who I feel that you can see is perhaps suffering a little bit or there’s a tension within their personality as a result of their tokenisation. They’re the only person in the room that, kind of, they’re only brought in for a specific purpose and then spat out again, the specific purpose being to solve the crime.

This is just a recurring theme in my work. I’m interested in what the consequences on the persona of the person are if you are a token. I think it has mental health implications. You see Poirot… In any of David Suchet’s performances of Poirot, you can see this…it’s often referred to as OCD tendency of him trying to make sure everything’s in its right place, being very, very self-conscious of himself. I can really identify with that kind of anxiety that I feel when I’m in white spaces as someone who is tokenised often, myself.

HBG: This part of me that… Yes, talking about being ashamed of your background, it’s like a huge admission, I think, actually. There’s absolutely nothing to be ashamed of coming from a low economic background, growing up in poverty but I’d been taught in lots of subtle and complex ways through education and going into the performing arts and the arts in general that it was something that I should suppress about myself. There’s a trend now for working class work I think so there’s something that I find difficult about capitalising on that identity for sure. I think that obviously those stories really deserve to be told. I really believe that but I guess, yes, there’s a question of who’s really benefiting from those stories which is interesting, I think. I don’t really know if I have any of the answers but, yes, I think it is ethically difficult because you want it to be doing good and not just contributing to the fetishisation of working class people which happens a lot, I think. Yes, I don’t want to just contribute to tokenism as well.

Tonight.

Hello, David Duckenfield. I’m Rebecca Jones.

Tonight.

I’m Joanna Gosling.

Tonight.

I’m Elizabeth I with Naga Munchetty.

Tonight.

One of these women with messy handwriting.

Tonight.

I’ll be bringing you all the latest this morning.

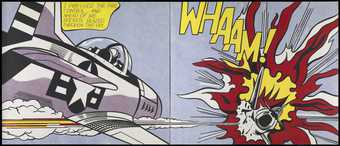

RJU: Just four months, actually, after the most famous Brixton riots. So at the time when a lot of people in the UK wouldn’t…a woman, a black woman wouldn’t have been welcome in a lot of their homes, Moira Stuart appears on their televisions, the face of the nation. So these screen prints here are, kind of, in browns and pinks, so playing a bit with the colours of a colonial map and through screen printing as well because I was interested in the idea of the edition. Obviously Andy Warhol uses that a lot, talking about ideas of mass media and how a person’s presence can become ubiquitous in society. I was also interested in making all of these actually original works using screen prints which all look like they could be editions but actually you realise there’s all of this original labour that’s gone into my creation of each of these individual images but also Moira Stuart’s performance. I just wanted to explore Moira Stuart’s image, revisit that as an image which like reoccurred in our childhood. They’re called Good Evening.

SJP: Okay, nice.

Persona is also about what you define as authentic.

LGB: Because everything’s performative there is a part of it that is playing with character but then what’s authentic and what’s not authentic is down to you and your own truth and your own experiences. For me, personally, I’m not playing a character. I’m making my performance work from the past like nine years or so I feel like now I’m at a place where I’ve found peace within myself and within my practice because I don’t need to explore any further my identity because I’m very sure of who I am. I feel like everything’s authentic and I know who I am and I know what I want. I know what I want to say. I know how I want to look. I know how I want to present myself to the world and be true to myself.

HBG: There were lots of people in the audience who I didn’t realise because I didn’t know anyone else like me because we, kind of, just blend in. I met a lot of people who came to see the show and realised that by looking at them you wouldn’t know where they came from because they’ve assimilated just like I’ve assimilated. Yes, they were affected by the themes in it themselves because they could see themselves in it. Even like my old drama teacher, yes, she was like, oh, I had to pretend to be something else in order to get ahead in teaching. Yes, it’s nice to know that it wasn’t just me.

SJP: Yes. Having the freedom to play and experiment with our persona can be an amazing way to learn about ourselves. We are free to decide where the performance starts, where it stops and if it has any limits. Our persona can also be a mask, a mode of survival or a way of protecting ourselves and our art against the prejudice of society. Persona seems to have as many iterations as Warhol has sides to his artistic image. Bob Colacello remembers him as so often being the outsider on the edge but he also managed to bring people together across all walks of life in a way which hadn’t been done before.

He was all at once the voyeur, the performance artist, the party-goer, the church-goer, the introvert and the extravert. What was authentic and what was cultivated will no doubt continue to divide opinion but it’s also why it continues to fascinate people. As society changes it shows new light onto Warhol and leads to a more nuanced understanding of him and his artwork but, of course, there will always remain a certain mystery which I imagine is what he would want.

Make sure you listen out for next month’s episode, the Art of Comedy hosted by Raven Smith. To explore more about the Art of Persona, visit the Andy Warhol exhibition at Tate Modern from 12th March to 6th September 2020. The exhibition is in partnership with Bank of America, with additional support from the Andy Warhol Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate patrons and Tate members. It is organised by Tate Modern Museum, Ludwig, Cologne in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto and Dallas Museum of Art. Curated by Gregor Muir and Fiontan Moran at Tate Modern and Yilmaz Dziewior and Stephan Diederich, curator, collection of 20th century art, Museum Ludwig, Cologne. The Art of Persona is a Tate Modern production presented by me Sandra Jean Pierre and co-produced with Hannah Dean. With music by Keel Her, Sleep Eaters, Black Manila, Scary Things and sound design for Opal Fruits by Ed Eldridge. Special thanks to Snaketown Records.

The.

Art.

Of.

End of transcript

What role does a persona play in the lives we lead and the art we make? We speak to artists, performers and DJs who use a form of persona in their work.

Experimenting with our persona can be a way to learn about ourselves and the world. But do we always know where the performance starts and when it stops?

The podcast is presented by Sandra Jean Pierre. Featuring artist Rosa Johan Uddoh, performer and activist Lewis G Burton, Scary Things hosts DJ Bempah & JK, choreographer and performer Holly Beasley Garrigan and magazine editor Bob Colacello.

The Art of Persona is a Falling Tree production for Tate, produced by Hannah Dean and Sandra Jean Pierre. With additional music by Sleep Eaters, Keel Her and Black Manila. Special thanks for Snaketown Records.

Find out more about Andy Warhol in our curator's tour and explore the exhibition room-by-room.

Want to listen to more of our podcasts? Subscribe on Acast, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or Spotify.