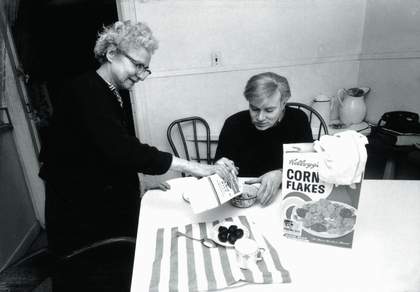

Ken Heyman

Andy Warhol at home eating Kellogg's Corn Flakes with his mother, Julia Warhola, 1966

© Ken Heyman, courtesy Woodfin Camp Associates

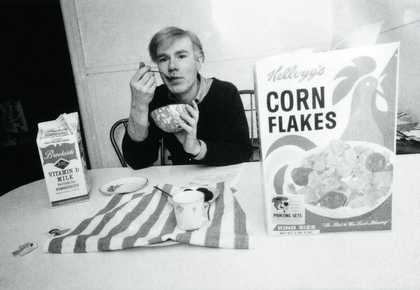

Ken Heyman

Andy Warhol at home eating Kellogg's Corn Flakes, 1966

© Ken Heyman, courtesy Woodfin Camp Associates

As is well known, Andy lived with mom for most of his life.[...] In Ric Burns’s epic Andy Warhol: A Documentary Film (2006), the art critic Dave Hickey speaks of Julia’s “secret kitchen workshop” as more crucial in Warhol’s artistic training than, say, his understanding of Duchamp. [...] Warhol, in a late interview, claimed that his mother’s home-made art, fashioned from cut-out food cans, influenced the making of his own tinned art.

Julia’s hand is unmistakable in Warhol’s early art, if only for her distinct, stylised handwriting which graces most of the artist’s books, some advertising assignments and many drawings. Titles such as “Angkor Wat, Cambodia” and “Bangkok, Thailand”, written in Julia’s familiar scrawl, appear on the drawings Andy made on his round-the-world trip in summer 1956; it would seem that, curiously enough, the artist had his mother caption and sign these travel sketches back in New York, on his return home. [...]

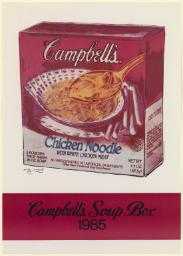

Andy Warhol

Campbell’s Soup Box 1985 (1985)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London

Paradoxically, it was by abandoning the American aristocracy of the Vanderbilts and Manhattan socialites with whom he lunched, and turning to his immigrant mother’s kitchen that Warhol found America’s most authentic images of itself - the Campbell’s Soup cans, the Coke bottles, the Daily News, the dollar bills, the Brillo boxes. Warhol stumbled across “the real America” in the pantry of a woman who never adapted to the American way of life, or mastered the English language, or altered a peasant lifestyle which revolved around daily visits to the local food store. The signature repetitiousness in his work, habitually interpreted by art critics as, say, the “machine-like alienation of modern life in our media-saturated world”, was more a reflection of the sad routine of a lonely, elderly woman who pasted stamps into books, stacked soup cans in her cupboard, or collected returnable Coke bottles. In this same light, the arrangement of 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans 1961–2 is not necessarily another incarnation of the Modernist/Minimalist grid, as it is generally read, but also a kind of calendar, marking the daily task of feeding one’s family. [...] With his oddball, foreign mother miraculously reborn through his supermarket art as the typical US housewife, Warhol too could reinvent himself as the quintessential American son.

Meanwhile, Julia Warhola, no longer asked to hand write the recipes and colophons of his pre-Pop work, and removed from her son’s daily working life, which had shifted from his home studio to The Factory, grew further away from Andy. She became more isolated, more reliant on alcohol and more invisible to those who knew him, despite roles in a couple of his more obscure films from the 1960s. When she became very frail around 1971, he sent her back to Pittsburgh, where she died about a year later. For the rest of his life Warhol claimed he suffered from guilt over those last months that they were apart.

The final, most direct, appearance of Mrs Warhol is in the remarkable posthumous portrait series Julia Warhola 1974. These are Warhol’s most intimate works. Gone are his acid colours, in favour of muddy, de Kooning-esque blurs of slate and a generally muted palette. Finger-painted (a rare technique for Warhol, though not unique around this time), they perform a gesture of touch bordering on sentimental kitsch, and suggest a brief return to the handpainted Pop style that he had so deliberately abandoned, to great success, in the early 1960s. [...] Julia Warhola stands out by contradicting almost every innovation which made the artist’s paintings revolutionary: the impersonal choice of subject matter, the machine-like handling of paint, the art-for-money ethos, the absolute focus on the present. All these essential hallmarks are tossed aside.

Andy Warhol

Sleep 1963

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

In 1963 Warhol made his second film, Sleep, in which his sleeping lover John Giorno is filmed for five hours and 21 minutes. It was, predictably, deemed unwatchable. Who could possibly endure watching someone sleep for so long? Well, a besotted lover, for one, pillow-gazing at this slumbering Adonis, or a mother admiring her children. Mrs Warhol, it is reported, watched Andy sleep, and liked to do so. Perhaps Sleep reproduces not just the mechanical gaze of the camera as it has been uniformly interpreted, but also its very opposite: an unflinching, loving gaze. [...] There is a sad, prophetic irony in Sleep. Andy Warhol died 24 years later in 1987, one early morning in a private New York City hospital with no one to watch over him – adequately, lovingly, attentively, like an angel, or a lover, or a mother.

This is an extract from Tate Etc: Issue 10, May 2007.