Friendship

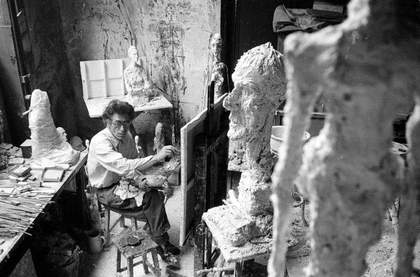

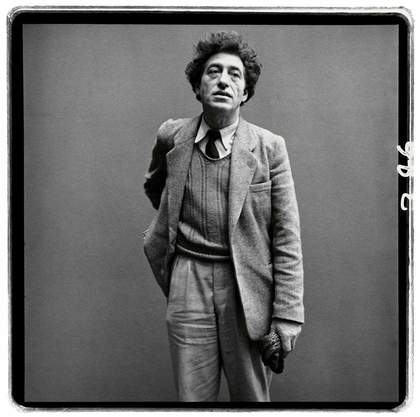

Giacometti and Samuel Beckett in Giacometti’s studio 1961

Photo: Georges Pierre. Courtesy Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris

‘Giacometti dead,’ wrote novelist, playwright Samuel Beckett in January 1966, ‘Yes, take me off to the Père Lachaise [cemetery] jumping all the red lights’. Alberto Giacometti’s premature death from heart disease provoked feelings of deep loss in the Irish writer. The precise moment of Giacometti and Beckett’s original meeting remains uncertain, but it is likely the two were introduced by mutual artistic acquaintances in Paris in the late autumn of 1937.

Their friendship however was not immediate. Beckett was prone to long, sometimes awkward, silences. Whereas Giacometti was notoriously extroverted and talkative. Their bond developed gradually, as a result of their shared artistic concerns and preoccupations.

Interestingly, the period in which they maintained the most frequent contact, spanning loosely from 1945 – 1960, is also the time in which both artists produced many of their most celebrated works.

Describing Giacometti’s approach to his work during this period, Beckett stated:

He was not obsessed but possessed […] I suggested that it might be more fruitful to concentrate on the problem itself rather than struggle constantly to achieve a solution […] But Giacometti was determined to continue with his struggle, trying to progress even if it was only by so much as an inch, or a centimetre, or a millimetre.

Style

Alberto Giacometti, sculptor, Paris, March 6 1958

Photographs by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation

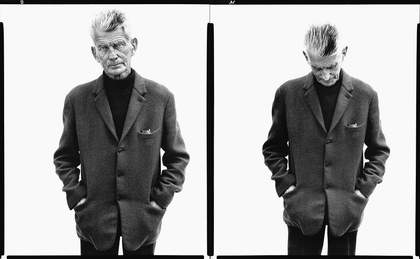

Despite both artists being described as scruffy or frugal, our growing access to archival imagery reveals both figures’ attention to personal style. Giacometti and Beckett favoured neat tailored clothing with simple clean lines made of good quality fabrics. They avoided pattern, often wearing tweed or fine wool suits with a fitted shirt, a skinny tie and a slim wool sweater underneath. Portraits made by some of the most important photographers of the twentieth century including Richard Avedon, Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Sabine Weiss, illustrate their emerging status as style icons.

Beckett and Giacometti’s common interest in style and fashion was part of a much broader engagement they shared with design, architecture and cinema. Giacometti’s fascination with the forms of ancient Egyptian architecture is well documented, as is the fact that he produced functional design objects such as lamps and vases in the 1930s.

Samuel Beckett, Writer, Paris, April 13 1979

Photographs by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Beckett similarly had other artistic pursuits beyond the purely literary realm, making a film entitled Film in 1965 and a series of television works beginning with Eh Joe in 1966, in which architecture and design play a central role. References to clothing and style frequently recur in Beckett’s work. In his play Endgame 1957, for instance, Nagg (one of two characters trapped in a dustbin) re-counts a favourite anecdote of Beckett’s in which a customer berates his tailor for taking so long to deliver his suit. ‘God made the world in six days’ complains the customer. To which the tailor humorously responds, ‘Yes sir, but look at the world and look at your trousers’.

Paris

Giacometti in his favourite coffee shop, seen from outside through the window c. 1950 Photograph by Ernst Scheidegger © 2017 Stiftung Ernst Scheidegger-Archiv, Zurich

At the time of Giacometti and Beckett’s first meeting, Beckett was living at a modest artists’ hotel in Paris called Hôtel Libéria. Located down a narrow alleyway, Giacometti’s studio (and home) was a mere twenty-minute walk from Beckett’s accommodation. The two would meet late at night, when they had finished work, in one of the Parisian cafés, such as Café Flore, Le Dôme or La Coupole, to drink and socialise. The cafés were the central hub of French cultural and intellectual life during the period, and other notable artists and thinkers, such as philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Genet, as well as painters Jean-Paul Riopelle, Joan Mitchell and Bram van Velde also visited these establishments.

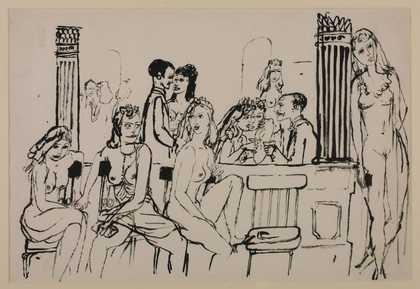

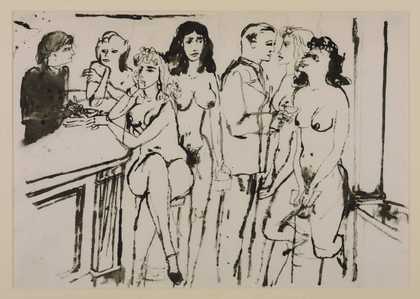

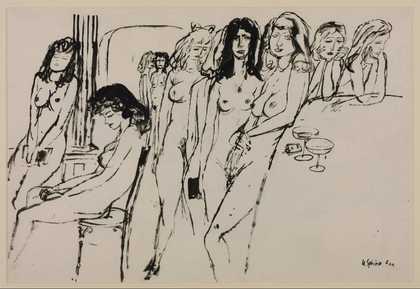

The pair would often leave the cafés in the early hours of the morning to embark on long walks around the city together. During their nocturnal rambles they frequently discussed each other’s work, although Giacometti is believed to have dominated these conversations with his anxieties concerning his artworks. Beckett and Giacometti’s nights routinely concluded with a visit to a brothel – the favourite being the legendary Sphinx located behind Montparnasse train station.

Walking at night in Paris was not without its perils. On 12 January 1938, Beckett was near fatally stabbed in his lung by a pimp on the Avenue Général Leclerc. On 11 October of the same year, Giacometti was knocked down by a vehicle operated by a drunken American heiress, while he stood at the Place des Pyramides. Leaving Giacometti unconscious on the pavement with a crushed foot, the woman swiftly crashed her car straight into a nearby shop window. The sculptor retained a limp for the rest of his life and Beckett had trouble breathing as a result of these unfortunate late night encounters.

In 1945, the two artists returned to Paris after the Second World War (Giacometti spent the war years in Geneva while Beckett fled to rural southern France and joined the Resistance movement), and their relationship drew closer. Beckett now lived in an apartment on the Rue des Favourites, remaining deliberately close to the cafés and Giacometti’s studio.

Work

Boris Lipnitzki Samuel Beckett, Jean-Marie Serreau and Alberto Giacometti assisting at a rehearsal of Waiting for Godot, Théâtre de l'Odéon, Paris 1961

Courtesy Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris

The lone, skinny plaster tree designed by Giacometti for Beckett’s 1961 re-staging of Waiting for Godot is the most recognisable outcome of their collaborations and an iconic theatrical set of the twentieth century.

Roger Pic Waiting for Godot, Théâtre de l'Odéon, Paris 1961. Courtesy Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris.

In the original 1953 production of Godot at the Théâtre de Babylone (a converted shop), Giacometti sat in the audience. The director Roger Blin had reportedly jerry-rigged a flimsy tree together for the production, using twisted wire coat hangers wrapped in tissue paper anchored to a piece of rubber foam. It is not hard to imagine that Giacometti might not have been impressed with Blin's shambolic attempts at scenography. When Beckett invited Giacometti to create an entirely new vision for his work in 1961, the artist readily accepted.

In an interview with art critic Reinhold Hohl, Giacometti described the process of constructing the stage set in his studio with Beckett:

We experimented all night long with that plaster tree, making it bigger, making it smaller, making its branches finer. It never seemed right to us. And each of us said to the other, maybe.

So what then became of the iconic tree produced by Giacometti and Beckett in 1961? Reportedly the work was destroyed in the May 1968 Paris riots when students occupied the Odéon Théâtre during the protests. The question of the tree’s symbolic presence and its contribution to the mythologies surrounding these two modernist figures is the subject of an artwork by Irish artist Gerard Byrne entitled Construction IV from existing photographs (after Giacometti) 2006.

Giacometti and Samuel Beckett in Giacometti’s studio 1961

Photo: Georges Pierre. Courtesy Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris

Gerard Byrne Construction IV from existing photographs (After Giacometti) 2006 © Gerard Byrne; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Giacometti died in 1966, while Beckett lived until 1989. Throughout their careers, both artists drew freely from a broad range of mediums including design, architecture, cinema and literature. This experimental approach to working has inspired many artists, such as Gerard Byrne, Bruce Nauman, Miroslaw Balka and Doris Salcedo, to name a few.

Dr Judith Wilkinson is a curator and art writer based in London. She is the author of Samuel Beckett: Artist and Curator (Bloomsbury 2018). Join her on a tour of the exhibition as she sheds further light on Giacometti and Beckett’s relationship.

Works by Alberto Giacometti © Alberto Giacometti estate / ACS+DACS in the UK