Welcome to our studio.

This is the area where we build things out of toothpicks and peanuts. You can see this is our collection, here on the left.

And the right is dedicated to Dodo eggs and drums, both of which are involved in current projects that we’re working on. That’s a dodo.

I can demonstrate how this works. The dodo was the first creature to be made extinct by human activity. This is a member of the Pussy Riot group that we photographed last summer in Moscow, using a new form of surveillance camera that doesn’t really create a photograph, but a kind of three-dimensional rendering of the human head.

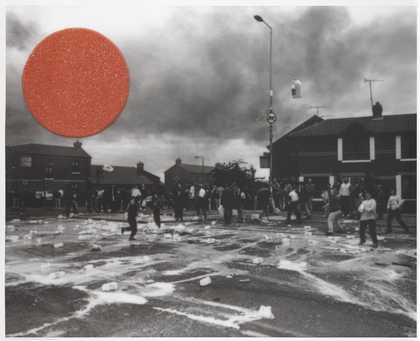

Adam and I started working in a very traditional documentary mode, taking portraits of people in the sort of places that photographers like to go to, you know, like psychiatric hospitals and war zones and prisons, and these kinds of places. And there came a point, in that process, where we, sort of, lost faith in the photographic engagement, and we reached a, sort of, crisis with the medium and started to make work that was much more referential, in a way, about photography.

Increasingly our practice has become about us acting as these kinds of hidden counter-insurgents to try and enter into a system of power.

The show at Tate at the moment is a really interesting premise, because it’s about the history of war and its relationship to photography, and that’s a theme that’s... that’s an enduring theme of our practice.

[Parade ground voices in background]

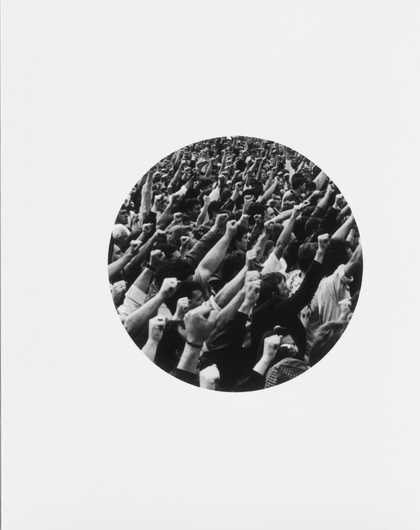

We decided to make an insurgent into the show with a performance involving 18 young military cadets aged 14 to 18, and these cadets are very inexperienced. They are just learning how to march, they are learning how to drum and play other instruments. They represent, for us, an example of a young person being pushed through the mechanism of the military.

[Drumming]

The drum roll is designed to create anticipation in that you imagine in the circus the drum roll, brrmm-shhh, and you know, a tiger jumps through the hoop. We’ve tried to extend it indefinitely, so it actually undoes its purpose. They all participate in keeping this drum roll going for a period of an hour. And the history of the drum in the military is a really interesting one. In the beginning they used to have a really young boy, up to the age of seven, marching in front of the troops in the old days when troops would just march in a line and be mowed down. And there was a so-called etiquette that the drummer boy would be spared if possible.

[Drumming]

Ten per cent of those 18 cadets will go on to see military conflict, and I think just the idea of seeing that body and looking at it as a piece of work, and just thinking about that body facing such, kind of, violence, somehow that will be the horror of it.

[Orders being shouted]

We are actually more interested in the outside world, the real world, than we are interested in the art world, and I think that’s a really important dictum that we try and follow.

[Drumming]