Mayo (Antoine Malliarakis) Coups de bâtons 1937 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (Düsseldorf, Germany) © DACS, 2022

Surrealism is a movement. Through their art, Surrealists wanted to channel the unconscious as a means to unlock the power of the imagination. Its powerful art continues to offer a new direction for exploration – from its beginnings in Paris in 1924 to today.

1. It was a transnational movement

Through the work of many interested individuals and groups, Surrealism found homes in many places. It went beyond national boundaries in its scope and impact and is seen in our Surrealism Beyond Borders exhibition as a transnational movement. Major artists from around the world were inspired and united by Surrealism – from Buenos Aires, Cairo, Lisbon, Mexico City, Prague, Seoul, and Tokyo. Different uses for Surrealism also took root at different points in history, from the 1920s to the 1970s. From Surrealists from Belgrade working in the 1920s, Shanghai in the 1930s, Santiago de Chile in the 1940s and Chicago in the 1970s.

2. Surrealism was a community

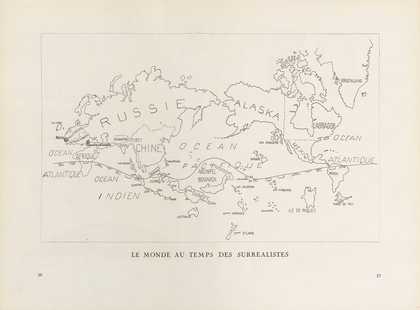

Le monde au temps des surréalistes” (The World in the Time of the Surrealists), from Variétés (Brussels), special Surrealist number, June 1929 Tate Library

What made Surrealism a ‘movement’ was the sense of a supportive community between like-minded artists and writers. They were united by certain shared ideals – making collective artworks, publishing manifestos and journals – their creative friendships, as well as their political and moral beliefs. Manifestos, in particular, were used to make public statements and often signed by those from many different locations. For example, an anti-colonial text of 1932 included contributors from Paris and Martinique, while the Arab Surrealist Manifesto was published by Chicago Surrealists in 1975.

3. Surrealism stood for freedom

Ramses Younan Untitled 1939 Sheikh Hassan M. A. Al-Thani © Estate of Ramses Younan

The Surrealism movement was sparked from a revolutionary idea in Paris around 1924. And while it has generated many familiar works – from Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone to René Magritte’s Time Transfixed – it has also been used by artists around the world as a serious weapon in the struggle for political, social, and personal freedom.

And from student, civil rights and anti-war protests to the decolonisation movement, Surrealism has served as this valuable tool. The movement found a place in political protests against Colonialism, Racism, Stalinism and Nazism, and the Vietnam War, for example. Léopold Senghor, poet, first president of Senegal and cofounder of the Black consciousness movement Négritude explained in 1960:

We accepted Surrealism as a means, but not as an end, as an ally, and not as a master.

4. Surrealism was about more than works of art

Surrealist imagery is probably the most recognisable element of the movement, though various visual arts, from exhibitions and journals of poetic, often humorous poetry and prose were also created to unite and exchange ideas. Sigmund Freud’s widely translated book The Interpretation of Dreams was a vital work for many artists’ approaches to Surrealism. Freud legitimised the importance of dreams and the unconscious as valid extensions of human emotion and desires, and his exposure and openness of the complex ideas around sexuality and violence provided a theoretical basis for much of Surrealism.

5.There are lots of women Surrealists

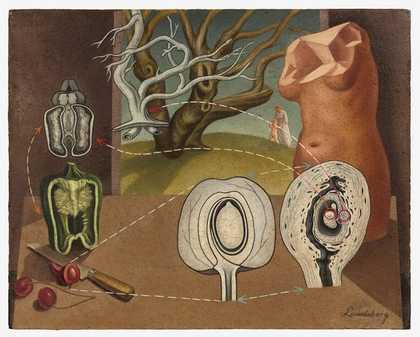

Helen Lundeberg Plant and Animal Analogies 1933–34 The Buck Collection at the UCI Institute and Museum for California Art (California, US) © The Feitelson/Lundeberg Art Foundation.

A host of intriguing women were associated with the Surrealist movement, including Eva Sulzer, Joyce Mansour, Cecilia Porras, Leonora Carrington to Suzanne Césaire and Meret Oppenheim. These artists and writers both championed Surrealist ideas and pushed against them to create work in which they could explore and counterbalance traditional narratives about gender, sexuality, desire, and repression. Joyce Mansour’s Cris (Cries, 1953) is one example:

May my desires be fulfilled on the fertile soil

Of your body without shame.