The advent of the Internet, new technologies, social platforms and grass-roots media has heralded a significant shift in collecting, disseminating and sharing information. Citizen journalism can be considered as the offspring of this evolution - an alternative form of news gathering and reporting, taking place outside of the traditional media structures and which can involve anyone. We live in the age of image consumption and data absorption. Everyday, a fresh wave of information reaches our computers and phone screens, but not only are we the recipients of this constant flow, we are now the creators. The liberalisation of information allows anyone to share and spread their personal experience of an event, in real time. This new form of reporting takes place ahead of or outside traditional media structures and can function as a firewall - holding media accountable for any inaccuracies or lack of news coverage.

The birth of citizen journalism is often attributed to South Korea where the first platform of amateur generated information, OhMyNews, was created. The principle was simple; anyone can take part in the process of creating information - as the notion of participatory journalism (another term for citizen journalism) implies. From reader to participant, citizens have now changed their status as a mere recipients of information, to providers. It is not necessarily something new, however. When Abraham Zapruder took his amateur film-camera and decided to go and record John F. Kennedy’s rally in Dallas, he inadvertently captured images of his assassination, which could be considered a proto-form of citizen journalism - as what really defines it is its inexpert nature. Zapruder supplied his film to the Secret Service to assist in their investigation. Whilst is was not the only film of the event, it was the most complete.

Film still from Abraham Zapruder's home-movie camera footage of President John F. Kennedy's assassination in Dallas, November 22, 1963

© The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

Participatory reporting allows storytelling. Personal experiences of an event reinforce their impact, with each testimony offering a new dimension. We can also argue that it resituates the individual within history and the way it is constructed. We have a tendency to think of history as a natural course of events that we automatically hold in our collective memory as ‘fact’ - but it is very much an artefact. History is about selecting and defining events, much like journalism does.

By engaging in the process of creating information, disseminating and consuming it, we could also argue that the era of information has promoted citizens to not only reporters but also as neophyte historians - making a moment matter.

Still from video footage of Ian Tomlinson immediately before being struck by police as he made his way home through the G20 protest in Central London, April 2009

© Ian Tomlinson Family Campaign

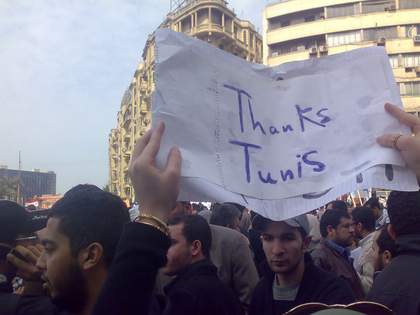

There are countless examples of this. The amateur video footage of Ian Tomlinson’s death during G20 demonstrations in London in 2009 brought a whole new explanation of the incident to light and a week later the true account of what actually happened was made public for the world to see, vastly contradicting the Metropolitan police claims of a natural death. A year later, in December 2010, when the death by immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia went viral on the internet, not only did it weave a new event into the net of history, it changed history’s course when it became the trigger element of a whole revolution, lighting the touchpaper for unrest and uprising. Angry and frustrated citizens in other regions of the Middle East watched things unfolding on social media, and Syria and Egypt would soon to follow suit.

Protesters in Tahrir Square Cairo 2011

© Ramy Raoof - via Flickr

Beginning in 2010, the Arab Spring displayed a new level of citizen engagement in reporting news, gathering live front-line footage and imagery, the monitoring of mainsteam media (over which there are often strict controls) and government authorities. Following the results of presidential elections in 2009, The Iranian Green Movement presented a new face of Iran to the world. In international media, Iran had been depicted as a deeply theocratic and extremist country. But when people around the world saw the Iranian youth discontent and collective unrest, a new image was formed, in stark contrast to the one that had prevailed for decades. More recently, the reports of police violence in Baltimore have triggered massive protests, and eye witness accounts have become a powerful watchdog challenging sovereign powers.

Hong Kong students clashing with police during the 2014 protests

© @hongkongprotester

But if citizen reporting has reshaped collective action and mobilisation, it can also be a new space of control and governmental interference. When citizen reporting flourished in Hong-Kong during the last year’s pro-democracy demonstrations, the Chinese government intimidated bloggers by threatening them with a 3-year sentence. In Istanbul, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government has increased censorship of the internet and went as far as temporarily blocking access to certain social platforms such as Twitter and YouTube used by the Turkish youth to critique and denounce politicians and gather for protests. In Iran, smart filtering systems allow the authorities to control some online content while in other places; citizen journalism has remained a way to hijack censorship protocols in conventional media. In Syria for example, citizen reporters have become the only source of information on the frontline, which journalists can no longer access.

History has shown the capacity of governments to control the production and distribution of information. Artists have long been entrusted to illustrate historically signifcant moments, though of course many were commissioned by victors with a story to preserve. War artists throughout history have been officially sanctioned by governments to faithfully record conflict and battle, but what do we know about the elements that were omitted? Can reporting ever be truly impartial? Citizen journalists are certainly not devoid of an agenda. How, then, can being both participant and reporter allow journalistic objectivity and neutrality?

Jeremy Deller

The Battle of Orgreave 2001

Colour video

Still frame

Photo: Martin Jenkinson © Artangel

The limits of citizen journalism lie in its innate freedoms; some essential yardsticks of traditional journalism can be neglected in favour of real-time reporting. The verification of facts and sources and the objectivity of a report don’t necessarily come in to play with hastily gathered material. Official news agencies and press outlets are increasingly relying on ordinary people on the ground most of whom can buy and operate a smartphone cheaply and with ease, but with this scenario comes challenges. These limitations also affect the free interpretation of images, but this is certainly no different in the mainstream media. Someone has made the call over how to frame, compose, caption, and distribute. When looking at a painting of a great historical battle, a viewer can perhaps visually differentiate the two camps involved in the conflict, as those differences were carefully rendered by the artist’s hand to aid the composition, such as in John Singleton Copley’s The Death of Major Peirson (1783). The lines become more blurred when fighting begins amongst neighbours who have live side-by-side in a community torn apart by differing political allegiances. More often than not in these live, raw images, we identify the warring factions as military and civilian. Uniform vs t-shirt and jeans. Authority vs man on the street.

John Singleton Copley

The Death of Major Peirson (1782–4)

Tate

But things are less obvious today. Without accountability of sources, images can be adopted and reused according to a specific agenda. Another problem rises to the surface: How can we track a source? How can we credit amateur generated imagery? Many sources get lost in the viral flow of clicks and shares and some apps such as Tagg.ly are trying to reinstate image attribution. This will become more vital the more legitimate this method of news gathering becomes. Citizenside, the French organisation set up to monitor, protect and verify material, also seeks to protect the sources – though in many cases people would rather remain anonymous if their safety is at risk, or a reprimand inevitable. It is open to anybody, and is now partnering with Getty Images and AFP, so that your iPhone snap may now make headlines.

The enthusiasm that citizen reporting arouses can also become a serious issue. This sudden engagement in public matters and current affairs sometimes blurs the lines between the role of simple reporter and a righter of wrongs. After the bombings during the Boston marathon, a manhunt was led by a small group who subverted their initial role as bystanders and established themselves as vigilantes on a hunt for the perpetrators of the bombings - which resulted in the false accusations against missing student Sunil Triparthi, who through the lens of social media was wrongly identified as a prime suspect in the attacks. If citizen journalism has emphasised the creation of a new counter-power, it can be argued there is a responsibility to self-regulate - to restrain the role to that of eye-witness, and not to descend into a simplified form of collective justice.

Through participatory journalism, the individual gains a new position in the course of an event, media, history and in the political sphere. By taking responsibility and power over information, citizen journalists question the centralisation of information. In America, six corporations control 90% of the media. In the UK, 70% of the national media market is owned by three major companies. It is now important for the potential and limitations of this new type of journalism to be highlighted and acknowledged. It has induced a renewal of media structures and places individuals at the centre of information gathering and history making, whether as a passive witness or a savvy auteur, citizens are making - and breaking - their own news.