Since its inception in the mid-nineteenth century, photography has been in an almost constant state of flux. The relentless technological innovation of the twentieth century has propelled photography through a series of transformations that have significantly reshaped the field. Of these many changes, that which has taken place in recent years is arguably the most profound of the medium’s history; Photography has now become an overwhelmingly digital pursuit, not only in terms of the devices which are used to take photographs, but also in the digital form of photographic images and the way they are distributed online. At the time this article was being written, over 30 billion photos had been shared on Instagram and approximately 300 million photographs are uploaded to Facebook each day. The Internet has become photography’s preferred, if not only playing field.

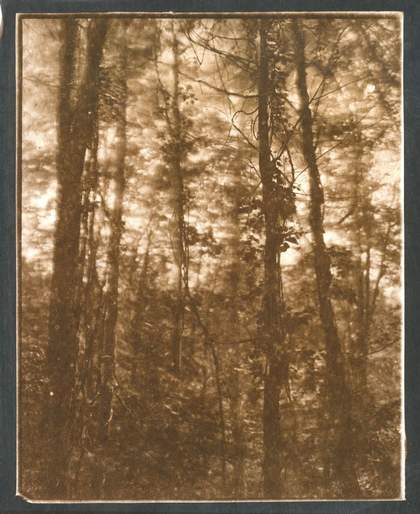

Koichiro Kurita, The Window Side, Montville, ME, 2013

8x10" salt print from Talbottype negative

Courtesy of the artist and sepiaEYE

Despite, or perhaps because of this, some photographers are bucking the trend by going back to the beginnings of the medium. In recent years, a shift toward early photographic techniques has occurred. These techniques are often labeled as ‘alternative’ photographic processes, with many focusing on the processes developed by William Henry Fox Talbot, notably the calotype and the salted paper print. While this community is largely made up of amateurs who focus on the mechanics of the process, for some contemporary artists, Fox Talbot’s legacy has informed not only their photographic practice, but also the philosophy and ideas behind their work.

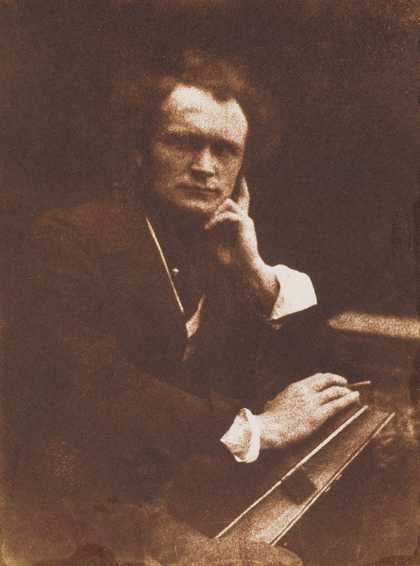

Born in Japan in 1943, Koichiro Kurita has been based in the United States since 1993. Though he began his career as a commercial photographer, he discovered his true photographic calling thanks to one of Fox Talbot’s contemporaries: Henry David Thoreau. His encounter with Thoreau’s book Walden led Kurita to turn his photographic practice towards nature. A master of the platinum palladium print, Kurita also makes use of the salted print in his practice. In the Beyond Spheres project, Kurita posed the question, ‘What if Thoreau had been a photographer?’ using Fox Talbot’s paper negative calotype process to produce salt or albumen prints.

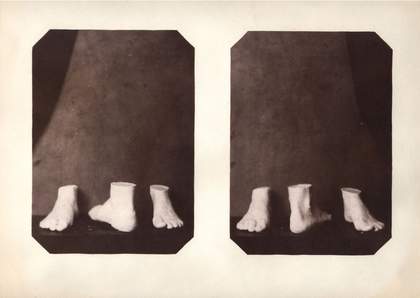

Dan Estabrook

Six Feet, 2010

Salt print, 14 x 11"

Kurita’s printing work reflects a concern shared by those artists working with these early photographic processes: a need to work with their hands and a recognition of the importance of a photograph as an object. The American artist Dan Estabrook is one of the foremost users of the salted paper print process today. For Estabrook, ‘Every handmade photograph is like a drawing or painting, or even a sculpture. It is an object first and foremost, with weight and form, not just a window into another world or another time.’

Mark Osterman & France Scully Osterman West Field Tree, 2010, from the Light at Lacock series

Digital pigment print from photogenic drawing negative

France Scully Osterman Pablo, 2002, from the Sleep series

Waxed salt print from collodion negative

The husband and wife duo Mark Osterman and France Scully Osterman, have made use of Fox Talbot’s early photogenic drawing technique as well as salt paper printing. For their collaboration The Light at Lacock they combined photogenic drawing with digital technology, scanning and inverting their negatives to produce prints. Reflecting upon the disappearance of the negative in the digital age, Scully notes that “new technology is both unsettling and full of promise. Digital photography doesn’t require a negative and the positive pictures are printed in pigments, which are more permanent than silver based photography. It’s a substantial step forward in the evolution of images made with light and one might expect that the early inventors of photography would have loved it.” Their practice illustrates how digital techniques can be successfully combined with early processes in order to develop new photographic approaches.

Danielle Ezzo

Two Women. Kindred Systems, 2012

Salted paper print, 20 x 16″

For some younger artists who belong to a generation of digital natives, the use of these early photographic techniques can be seen as a radical gesture. Born in 1984, Danielle Ezzo is an American photographer who has worked with many early photographic processes including cyanotypes, gum bichromate prints and salted paper prints. For her series Kindred Systems, Ezzo combines salt prints with drawings, a recognition of the early link between the two disciplines and am homage of sorts to Fox Talbot’s failed drawings with the camera lucida. As she explains: ‘I try to find ways to insert my hand into whatever process I’m working with. It’s especially interesting to me in conjunction with photography because you do not expect to see the artist’s hand in such a direct way. By drawing directly onto the negatives, I was breaking the expectation of the role of both the artist and the photograph.’

Matthew Brandt

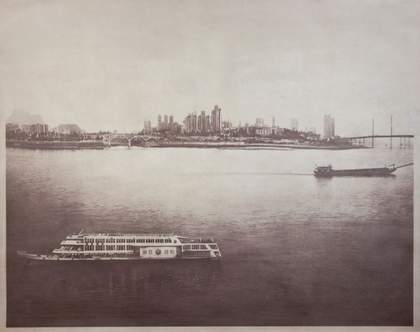

Two Ships Passing, China, 2011

Salted paper print with Xianjiang River water

42 x 52 1/2"

Matthew Brandt (born in 1982) has used the salted paper print in order to connect the photograph to its subject in a very direct way. While experimenting with the process, Brandt realized that he could use the salt present in most materials. In Lakes and Reservoirs, he used samples collected from the bodies of water he was photographing to soak his prints, thereby truly making his subject a part of the finished work. Brandt also experimented with this technique in his Portraits series, where the sitter’s bodily fluids became an active part of the chemical process.

Many of these artists experiment with early photographic techniques in an attempt to search for answers to photography’s current existential crisis. According to Estabrook, ‘Now that we can clearly say that all the daily and vernacular uses of photography are digital - our snapshots, our vacation photos, our school pictures, our advertising, our pornography - then that means chemical photography is finally at the place that painting may have been when photography was invented: free to abandon its usefulness to concentrate on being art.’ Whether driven by nostalgia, a desire to explore photographic history, or simply by a thirst for the material in the age of the virtual, the salted paper print continues to thrive in the digital age.

Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840 - 1860 runs until 7June 2015. Book tickets here.