Suzanne Lacy

The Crystal Quilt 1985–7

© The artist Photo: Gus Gustafson

Performance has always been interconnected with society more widely. Collaborative, participative and public, artists have fused comments on everyday life with political engagement, creating actions and performances that respond to and are fuelled by many of the activist movements throughout the twentieth century, as well as today.

The Beat writers and their work are a good example of this: specifically Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. Ginsberg was part of what came to be known as the Beat generation, (mainly) young men (including Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs) writing about their own lives, exploring and escaping the strictures of 1950s society through drink, drugs and sex.

Ginsberg performed Howl for the first time in 1955, at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, and it was published in a collection of Ginsberg’s works the following year. Breaking the rules of both poetry and society, the energetic visionary poem railed against the prevailing consumerist ideals of America at the time, and described the travails of his contemporaries fighting against this world, released only by destruction and madness. What made the poem most well-known, however, were its references to sex, specifically homosexuality, which sparked an obscenity case. Though eventually overturned, the publicity surrounding the case brought Howl to the attention of a global audience, increasing its ‘counter-cultural’ influence far wider than the sympathetic San Francisco Bay area. Howl and the ideas of rebellion it explored became one of the key moments in the rise of the youth activist movements of the 1960s.

Of course, politically motivated art and performance was not new in the 1950s. Before and between the first and second world wars in Europe, a number of art movements such as the Italian Futurists, had spread their political or anti-establishment ideals through various artforms, including performance. But after the Second World War, changing social mores, supported by mass media communication, and the rise of youth culture (as the Baby Boom generation became young adults) saw wide-spread protests against various parts of the political and social status quo.

The Civil Rights Movement in the US was gathering pace in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The use of non-violent protest methods and civil disobedience (based on the actions of Gandhi in India) to highlight and protest the racial segregation of public areas in the US, such as sit-ins or ‘freedom rides’ on segregated transport, set the model for protest and mass actions in public spaces.

In the mid-60s, after the nuclear Cuban Missile Crisis and the assassination of US President John F. Kennedy, anti-war protests against the Vietnam War were also in full force, with young men burning their draft cards and marches and demonstrations taking place across the US and more widely. Musicians Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, with their folk-inspired protest songs, became figureheads for the protest movements and art also took its place in protest in serious and humorous, direct and oblique ways.

Aldo Tambellini

Black, Electromedia Performance at Black Gate Theatre, New York 1967

© Courtesy Aldo Tambellini Photo: Richard Raderman

Pioneer of multimedia environments Aldo Tambellini put on collaborative performances such as 1965’s BLACK ZERO, which incorporated live performance, poetry and projection and had strong revolutionary and social change messages, commenting on the racial situation in America.

Black Zero is the cry from the oppressed creative man. There is an injustice done to man which is not forgivable.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s Bed Peace 1969 was a bed-in, a variation on the sit-in. Both protest and artistic statement against war, the pair sat in bed for world peace, and garnered a huge amount of publicity, mainly due to Lennon and Ono’s fame and the fact that the event was part of their honeymoon, but also because what they were performing articulated youth attitudes and concerns of the time.

Other artists associated with Fluxus (as Ono was) often took their actions into the street, aiming to break down the barriers between art and life, and bring the revolution to the everyday. In Prague, Milan Knížák and others in the AKTUAL group were often stopped by the police as they built environments or performed personal and participative acts in the streets of Prague, such as his Demonstration for One 1964.

Hi Red Center performed their Street Cleaning Event (Be Clean!) in Tokyo and New York, commenting on the Japanese beautification of Tokyo in preparation for the 1964 Olympic Games. The government had issued instructions to Japanese citizens to behave in a more sanitary manner during the Games, including not spitting on the street. Some passers-by thought the artists, dressed in lab coats and scrubbing at the pavements, were actually part of the Olympics planning rather than a mocking comment upon it.

A revolution in everyday life was also the core of the theoretical underpinnings of the Situationist International’s part in the May 1968 student uprising. Situationist International grew out of avant-garde artistic movements like Dada, Surrealism and Lettrism. It began as an artistic movement with a rigorous theoretical and left-wing political basis which aimed to bring about a revolutionary union of everyday life and political engagement, through play and freedom, rather than what they saw as the passive acceptance of mainstream consumer culture.

1968 saw a move to violent protest, perhaps reacting to the sense that non-violence began to feel powerless, especially after the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy and the coverage of shocking events taking place in the Vietnam War. Across Europe, from Poland to Prague to Paris, young people, academics, artists and writers were organising, marching, occupying buildings and often engaging in violent clashes with the police. While in Poland protests were about censorship, and the Prague Spring (ended by Soviet tanks rolling in to the city) intended to reform the political situation in Czechoslovakia, the protests in Paris, London and New York focused on revolt against authority and consumerist culture.

French students were exposed to and took on anti-establishment Situationist ideas such as Guy Debord’s 1967 Society of the Spectacle, which argued (the Marxist idea) that consumer society had reduced everything from direct experiences to mere appearances, and that the avant-garde and mainstream life should be brought together. Students in Paris went on strike, leading to confrontations with the French police and street battles in the Latin Quarter, and then a general strike across universities and industry. Painted graffiti appeared around Paris, including slogans such as ‘Le patron a besoin de toi, tu n’as pas besoin de lui’ (The boss needs you, you don’t need him) ‘Je suis marxiste tendance Groucho’ (I am a Marxist, of the Groucho tendency) and famously, ‘Sous les paves, la plage!’ (Under the pavement, the beach!).

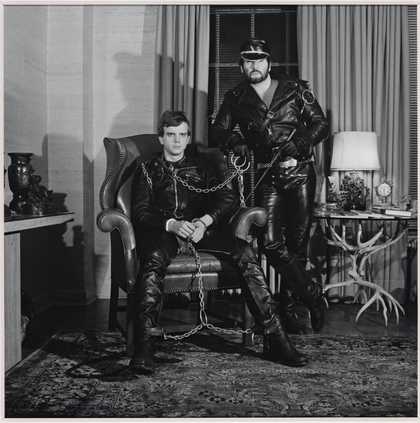

In 1969, a police raid on a New York bar, the Stonewall Inn, sparked several nights of violent resistance to the routine police harrassment of the gay community. This fight back marked the beginning of agitation for civil rights for those identiying as LGBT and what came to be known as gay pride, a huge cultural shift for a time when few were willing to be openly identified as gay. In the 1960s and the years that followed, artists and film-makers like Andy Warhol, Jack Smith, Robert Mapplethorpe and Catherine Opie, spaces like Dixon Place or Women’s One World Cafe and musicians such as Iggy Pop and David Bowie continued to break down these barriers. Later, artists also began commenting on fear, preconceptions, misapprehensions and stigma around HIV/AIDS.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter (1979)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

David Wojnarowicz’s text work Untitled (One day this kid…) 1990 dealt directly with the persecution of gay men through a telling of the future of a young boy. Part of the campaigning body ACT-UP (the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power), in his Silence = Death film from the same year Wojnarowicz sewed up his mouth, creating a shocking and compelling image to protest against the inadequacy of AIDS research and treatment.

Others were thrust into campaigning by the treatment of their work by the media. Body artist and performer Ron Athey’s 1994 Four Scenes In a Harsh Life included a section where Athey cut into the back of fellow performer Darryl Carlton (Divinity Fudge), and then pressed absorbent paper towels against the wound, creating a print. The towels were then pinned to a clothesline pulley that was wound out over the audience. Though Carlton was not HIV positive, a media storm was generated about the erroneous idea that Athey (HIV-positive himself) was exposing the audience to HIV-positive blood. The furore around the work forced Athey to defend the public funding of art that might deal with issues that troubled mainstream society. This was despite the fact that Athey was not publicly-funded, though the Walker Art Center (where the work was performed) had been.

The other equality and civil rights movement on the rise was feminism. The introduction of the contraceptive pill ushered in a new wave of sexual freedom for both women and men, and gave women safe control and choice about becoming pregnant. Marriage and family was no longer the only goal (or option) for women, and more and more women were educated to university level. Women protested in mass marches throughout the 1970s, on social issues such as equal pay, the objectification of women in beauty pageants, against war, and for nuclear disarmament. Particularly in the US, female artists, traditionally underrepresented in the male-dominated art world began to use performance, and often their bodies, to make work that directly engaged with the roles of women in society and social issues in general. As feminist artist and educator Judy Chicago put it:

Performance can be fuelled by rage in a way that painting and sculpture cannot.

VALIE EXPORT

Action Pants: Genital Panic (1969)

Tate

VALIE EXPORT’s TAP and TOUCH CINEMA 1968 took the traditional view of the woman’s body as something to be looked at, specifically in the world of film and cinema, and made that voyeurism public. Carrying a box attached to her bare torso, participants were invited to put their hands through the curtain covering the opening and touch her body. EXPORT called this the first genuine women’s film, as the woman controlled the display of the female body. EXPORT’s notion of ‘expanded cinema’ was that the live body activated the projected film. Forcing those interacting with her body to meet her gaze, she challenged the dehumanisation of woman as object in film as well as taboos around sexuality and physical experience. Her work Action Pants: Genital Panic 1968 took a similar theme as she walked through the rows of an art house cinema in Munich wearing crotchless trousers, her genitalia level with the seated spectators’ faces, again forcing the public viewer to engage with the live female body rather than images on the screen.

Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll 1975 also confronted viewers with female genitalia, though with a different meaning. Standing naked on a table, Schneeman read from a scroll slowly unrolled as she pulled it from her vagina. The text was a conversation setting ideas traditionally associated with women, such as intuition and bodily processes, against notions of order and rationality, seen as male. For Schneeman, the body was a source of knowledge and experience and the vagina particularly as a site of sexual power.

I thought of the vagina in many ways – physically, conceptually: as a sculptural form, an architectural referent, the source of sacred knowledge, ecstacy, birth passage, transformation.

Female artists also focused on their lived experience, making public those parts of a woman’s life that had been seen as taking place behind closed doors. Judy Chicago taught on the germinal feminist programme at the California Institute of the Arts, along with painter Miriam Schapiro. Rejecting both her maiden and married names, she changed her name to Judy Chicago in 1971, signalling her move into a feminist art practice and a rejection of male domination. The influential installation Womanhouse 1972 took place throughout a house in Los Angeles, and showed the work of 26 students as well as Chicago and Shapiro, including Chicago’s Menstruation Bathroom (a bathroom with a bin overflowing with bloody tampons) and a series of performances exploring the lives, activities and roles of women. Chicago’s most well-known work, The Dinner Party 1974–9 came from previous works such as her Great Ladies series and her realisation of the erasure of female achievements throughout history. The Dinner Party is a triangular open table set with 39 places, each commemorating an important female historical figure or goddess, resting on a tiled floor inscribed with the names of 999 other important women. The Dinner Party was exhibited in 16 venues in six countries on three continents to a viewing audience of over one million people, making it an important touchpoint in the history of feminist art.

Mary Kelly’s Post-partum Document 1973–9 presented the scenes and ephemera of the first six years of her son’s life as important documents. Susan Hiller also methodically documented her pregnancy in 10 months 1977–9, photographing her expanding belly. Though these works were broadly dismissed or disregarded by the mainstream art world at the time, they have been understood since as an important move in the representation of women and women’s life, by women, in art.

Others were participative in their approach. Suzanne Lacy’s Crystal Quilt 1985–7 was a three year public artwork, exploring how the media portrayed ageing and what the role for older people in public was. It culminated in a performance on Mother’s Day in 1987, when 430 women aged over 60 from Minneapolis gathered together and shared their views on growing older in a live TV broadcast. Staged on a series of tables laid out in a setting designed by the painter Miriam Schapiro, the women’s hands laid on the coloured tablecloths changed at prescribed intervals to echo the shapes of quilt blocks (the quilt being an emblem of the traditional sharing of North American female experience). The final performance was broadcast live on a public television network.

In 1985, MoMA in New York showed an exhibition entitled An International Survey of Painting and Sculpture, purporting to showcase the most important contemporary art. Many noticed that of the 169 artists included only 13 were women and all where white. Though women protested outside with placards, a few noticed that this was not a one-off, and that in fact, women and artists from minority ethnic groups were still poorly represented in major art institutions. The Guerilla Girls (a group of anonymous female artists) started pasting up posters around SoHo that pointed out these poor numbers, aiming to embarrass the various groups of the art world: artists, dealers, collectors, critics. Since then, the Guerilla Girls’ activism has continued to appropriate the visual language of advertising to create witty and ironic posters and prints as well as forums, protests and actions, where they wear their trademark gorilla masks to conceal their identity.