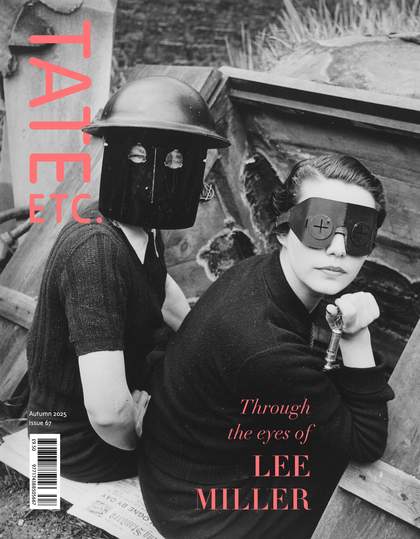

Frida Kahlo

Self-Portrait with Monkey 1938

© 2005 Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust and INBAL

Frida Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera both used to refer to her as ‘la gran ocultadora’. The expression is an odd one, meaning ‘the great hider-away’, as if she were a mystery-maker. Fifty years after her death, Kahlo is credited with having displayed in art for the first time the interior reality of a woman’s life. She is idolised for having revealed essential truths about all kinds of female experience – about disablement, rejection, miscarriage, suffering, Mexican-ness, Jewishness, homosexuality, revolution, subversion, devotion – in 200 or so coloured images, painted in oils on metal or hardboard, and occasionally canvas, the greater part of them depicting or purporting to depict the painter herself.

As a self-portraitist Kahlo fits right into the tradition of women’s painting. Her contemporaries include other practitioners of the same genre, Leonora Carrington and Leonor Fini, for example. Since the dawn of Western art, women have painted many more self-portraits than their male counterparts; indeed, a significant proportion of their rather small number are known to us only from a single surviving self-portrait of the artist as a beautiful young woman. A woman painter was a curiosity of just the kind that collectors wanted in their cabinets. Gallant patrons complimented them by asking for no other subjects from their hand but their own fair selves, and an artist such as Angelica Kauffman, to name just one, was in no position to refuse. Like Kahlo, she painted herself time and again, in a variety of costumes, sometimes as an allegorical figure, as Kahlo does. What is not clear is whether the women portrayed are faces or masks; whether the reality is not inevitably ocultada.

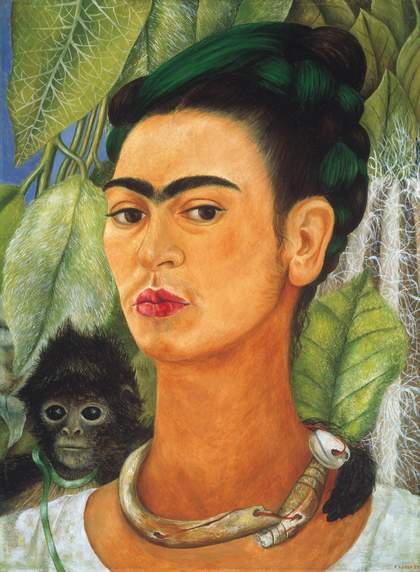

Frida Kahlo

Self-Portrait with Small Monkey 1945

© 2005 Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust and INBAL

In Kahlo’s bust-length self-portraits, the pose is almost always the same: shoulders square on to the viewer, parallel to the picture frame; head a quarter turned, usually towards the left shoulder; eyes looking back to the viewer in a direct, unwavering stare. The hairiness of the face is usually exaggerated – the eyebrows meet over the nose in the famous unibrow, and the upper lip is conspicuously furred with dark down. How closely this icon resembled the artist can be easily judged from photographs of Kahlo, of which there are many more than there are works by her hand. When she was aware of the camera she did her best to reproduce the slight head turn and the unsmiling stare of her painted image. She seldom allowed images of her face to express anything beyond her identity, in a version as stylised as a passport photo, showing the obligatory one ear. All the portraits say, in the same tone of voice: ‘I am Frida Kahlo’. This is her achievement – the lifelong performance of Frida Kahlo. In this too she remains part of the tradition of the female artist as outlandish phenomenon: Rosalba Carriera and Angelica Kauffman are just two of the ‘paintresses’ (as they were called at the time) who were obliged to entertain their patrons by playing musical instruments and singing, as well as making artworks

It is no small praise to say that Kahlo was the first ever true performance artist, that the performance lasted all her life long, and that she was indefatigable in presenting it, year on year, day by day. At least as much creative energy went into dressing the part as in drawing and painting it. Fashioning herself also involved the creation of an appropriate setting with intriguing props – animals, flowers, a plaster skeleton atop her bed, a foetus in a bottle and all the other impedimenta and phantasmagoria that made up the house at Coyoacan. She also generated a text to accompany and eventually to commemorate the performance, the selective and partly mythologised account of Frida Kahlo. One is not surprised to find that Madonna is a fan, or Jean Paul Gaultier. Both are performers and both live by manipulating the same materials as Kahlo. She might be delighted that her family, to whom she left no paintings, has succeeded in registering her name as a trademark, though if she could see the shapeless cheap garments and accessories marketed on the world wide web by fridakahlo.us, she would be outraged.

A seductive parallel with the Frida Kahlo phenomenon is the career of her exact contemporary, the ‘Brazilian bombshell’ Carmen Miranda, born Maria do Carmo Miranda da Cunha in provincial Portugal in 1909. Like Kahlo, Miranda was vulgar, charming, foul-mouthed, irreverent, exuberant and tiny. While Kahlo developed a variant on Tehuacan costume, Miranda adopted and exaggerated that of the fruit vendors of Bahia. Kahlo’s pictorial language was derived from popular art forms; Miranda adapted the dance music of the favelas of Salvador. Like Kahlo, Miranda found favour in the United States; in 1940 Saks brought out a line of costume jewellery based on the heavy beads and extravagant headgear that she had made her trademark. Like Kahlo, Miranda composed poems and painted. Like Kahlo, she died young and childless after years of bitter suffering. Unlike Kahlo, she was not married to a national hero; it is generally thought that her gringo husband abused her, and that years before she died she was, like Kahlo, heavily drug-dependant. Kahlo is now being honoured by retrospective exhibitions in the world’s great art houses; in Brazil Miranda’s Bahian fashions are being revived, and EMI-Odeon Brazil has remastered and issued six hours of her music. Yet the instructive parallel is never drawn. These two remarkable women, with so much in common, remain in separate worlds.

Orlan is probably not a great fan of Frida Kahlo, yet in many ways her art practice is an elaboration on the Mexican’s precedent. From the beginning of her career in the 1960s when she photographed her body as if it were sculpture, Orlan has remained fascinated by her own image and her power to modify it, portraying herself in the guise of the Madonna and as Sainte Orlan, creating costumes by using the sheets from her own trousseau and, ultimately, by recourse to surgery. Kahlo’s biographers have been puzzled by her frequent operations, and have questioned whether they were really necessary. Orlan’s surgical performances began in 1979 when she was diagnosed as having an ectopic pregnancy necessitating an emergency procedure. By the time the artist was in the operating theatre she had arranged for a video camera to record the event, and for the tapes to be ferried as fast as they were recorded to the arts centre in Lyon, where they were immediately screened in an extraordinary updating of Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital of 1932. Kahlo painted herself in the lithotomy position and bleeding after the event; Orlan had herself portrayed in the stirrups in real time during the event. The difference is no more than one of epoch and available technology. The shock value in the different contexts is the same.

The French artist’s first operation was the precursor of the nine surgical performances that make up La Réincarnation de Sainte Orlan, in which, in much the same spirit as Kahlo exaggerated her unibrow and the dark brown fuzz on her upper lip, Orlan acquired two bumps on her forehead and the chin of the Botticelli Venus. The procedures were all photographed and recorded on video with live commentary by the artist herself, watching completely unmoved as her face was sliced open, turned inside out, scraped and remodelled. In the following days she would pose, immaculately coiffed and made up, for glamour shots of her horribly bruised face. This is very reminiscent of the woman who made a personal appearance at the opening of her one-man show in Mexico City in 1953 in her hospital bed, specially transported to the gallery for the purpose. All Kahlo’s appropriations were stylish; the names she dropped were the names to drop. Just so, when Orlan went under the knife, she had Paco Rabanne and Issey Miyake design clothes for her and the surgical staff, and poets and musicians accompanied the procedure. In Orlan’s carnal art, the events portrayed actually happen, while her predecessor insisted that she was not portraying dreams as a Surrealist might, but showing her reality.

To consider Kahlo as a painter only is to confuse one part of the performance for the whole and, moreover, to find her wanting. As a maker of two-dimensional images she is, despite the vast range of motifs she includes, deliberately unsophisticated. She does not want anyone viewing her work to be sidetracked by the paint quality or seduced by the composition. The paintings function as advertisements; they are the hoardings announcing the stages in the performance. The notion of art that Kahlo acquired along with Diego Rivera was fundamentally didactic, as were the Mexican ex-voto paintings which defined the narrative strategies that she would eventually use. The Kahlo icons are arresting without being interesting from a painterly point of view. The shock effect is not derived from the treatment of the objects depicted, or from any drama or energy compressed within the composition, but is felt simply as a consequence of identifying the motifs, as it were, in a diagram. That these are drawn from a vast range of sources, mythological, anthropological, historical, metaphysical, pyschoanalytical and folkloreistical, is only to be expected. To claim that these vast realms are explored when they are simply sampled, is to go too far.

Within the pièce d’identité formula there are not-so-subtle falsifications; no human neck was ever as long as Frida Kahlo in her self-portraits. We know from photographs that her shoulders were narrow and sloping; those in the painted images are usually square and broad. By such unsubtle shifts, while making herself recognisable by the trademark eyebrows and moustache, Kahlo also makes herself monumental. She may have wanted her public to believe that she painted what came into her head ‘without any other consideration’; in fact, she did as every painter does – she produced what she wanted others to see. The formulaic reduction of her face functions in the same way as any icon: as a mnemonic, rendering it memorable. The fixed immobility of the likeness signifies eternity. Revealing though the strategy may seem, it is anything but intimate. The personal, being represented in impersonal, archetypal terms, becomes universal. This is by no means to say that Frida Kahlo was an ordinary person pretending to be extraordinary. Her devotion to this process was extraordinary. The performance was her reality.

Louise Vigée le Brun

Self-Portrait 1787

Other female self-portraitists, most of whom were obliged to earn their living producing portraits of richer people, flattered themselves in a very different way, because they needed to persuade their patrons that they could make them look glamorous and yet recognisable as them-selves. Vigée Le Brun prefigures Kahlo in that she performed the role in which she depicted herself in real life as well as on canvas. Anxious to bring her corsetted and coiffed clientele into the rosy glow of neoclassicism, she removed her own corset and donned the robe en gaulle, the high-waisted white muslin dress that was to become the uniform of the neoclassical female on both sides of the Channel. She wore her own brown hair unpowdered and uncurled, winding scarves about her head instead of decking it with jewels and feathers. The great difference between the two is that the French artist was inventing a style for a generation, whereas Kahlo’s style is reserved unto herself. Vigée Le Brun also falsified aspects of her representation; in her numerous self-portraits she always showed her mouth as tiny, her teeth no bigger than seed pearls. More importantly, the flesh tones are infinitely seductive, a sign that she could do as much for her sallowest patron.

Frida Kahlo was uninterested in portraying anyone but herself. Her portraits of other people are perfunctory. The Gelmans were important collectors of both her and Rivera’s work. When it was Rivera’s turn to paint Mrs Gelman, he permitted himself an almost laughable degree of flattery, draping her impossibly elongated figure in a clinging white evening gown obliquely across the canvas from upper-right corner to lower left. Kahlo produced a kit-cat portrait of a tizzy blonde in a fur coat, blankly full face and virtually neckless. Though she portrayed herself as unforgettable, she made Mrs Gelman entirely forgettable. So powerful was his wife’s version of her own image, that when Rivera painted her he gave himself no option but to reproduce a pallid version of it.

In her lifetime, though she had her following among style gurus in New York and Paris, Kahlo was famous principally as the exotic wife of the heroic muralist Diego Rivera. He believed that the world stood on the brink of socialist revolution; in fact, what was dawning was the age of individualism. Now it is Rivera’s social realism that seems naive, while Frida is right on the money. El Abrazo de Amor del Universo, la Tierra (México), Diego, Yo y el Señor Xolotl 1949 shows Diego as a grey-skinned bloated baby lying in Frida’s lap, like the body of Christ lying in the lap of the Virgin in a votive pietà. Sure enough, 50 years after her death Kahlo is the subject of a veritable cultus, patron saint of both lipstick and lavender feminism. It is no more than she deserved.