Gustav Metzger

Recreation of First Public Demonstration of Auto-Destructive Art (1960, remade 2004, 2015)

Tate

The term was created by Gustav Metzger shortly after the end of WWII, during an era of political unrest known as The Cold War. The invention of nuclear weapons and their use by the U.S against Japan in 1945, left a deep impression on the whole world. In reaction against this the anti-war group The Committee of 100 (supposedly named by Metzger himself) was formed in 1960 and Metzger began making paintings using acid as a form of creative protest.

Metzger first mentioned Auto-destructive art in his article Machine, Auto-creative and Auto-destructive Art in the summer 1962 issue of the journal Ark. However he had been practising this form for a few years, creating his first acid paintings in 1959 as another means to protest against nuclear warfare. These works were created by spraying acid onto sheets of nylon, which produced rapidly changing shapes in the dissolving nylon making the work both auto-creative and auto-destructive:

The important thing about burning a hole in that sheet, was that it opened up a new view across the Thames of St Paul’s cathedral. Auto-destructive art was never merely destructive. Destroy a canvas and you create shapes. (Metzger quoted by Stuart Jeffries, The Guardian, 2012)

Auto-destructive art was inherently political; also carrying anti-capitalist and anti-consumerist messages. It addressed society’s unhealthy fascination with destruction, as well as the negative impact of machinery on our existence.

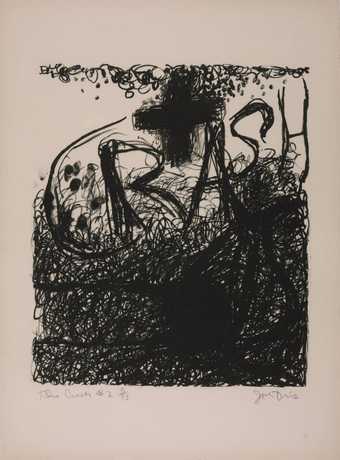

In 1966 Metzger and others organised the Destruction in Art Symposium in London. This was followed by another in New York in 1968. The symposium was accompanied by public demonstration of auto-destructive art including the burning of Skoob Towers by John Latham. These were towers of books (skoob is books in reverse) and Latham’s intention was to demonstrate directly his view that Western culture was burned out.

In 1960 the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely made the first of his self-destructive machine sculptures, Hommage à New York, which battered itself to pieces in the Sculpture Garden of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The Manifestos

Metzger released two manifesto’s clarifying the term. The key principles are as follows:

Time – The work must, within the course of 20 years, return to its original state of nothingness.

Self-completion – Metzger emphasised the importance of the process continuing once the artist sets it off, avoiding any sense of ownership over the development of the piece.

Participation – This movement is centred around public participation. Although the artist can set off the process, it must happen in a public space. It is not to be consumed privately for a select group.