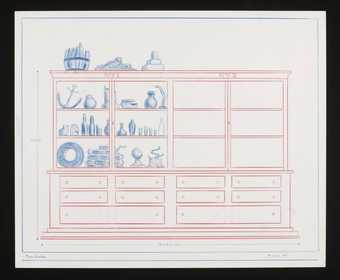

An artists’ archive usually consists of documentation and ‘secondary material’. This includes material traditionally created alongside an artwork, which might include photographs, audiovisual material and sketches. It also includes practical records such as letters, financial papers or exhibition material. This material can be physical or born-digital.

Documentation has become very important for art practices such as performance, land art and conceptual art. This is because many of these works cannot be re-performed and re-staged. For artists making time-bound work, archival material has often come to represent the artwork within museum collections.

Tate holds two archival collections. Tate Archive contains material relating to the history of British art by artists, arts organisations, and prominent art world figures. Tate’s Public Records Collection contains the archival records of Tate’s own history. These can be accessed via the Reading Rooms at Tate.

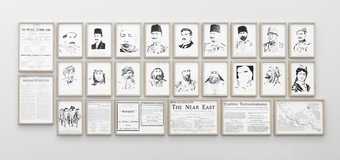

There are also artists who explore both the appearance and the workings of archives through their art. In 2001, Jeremy Deller orchestrated the reenactment of the clashes between police and striking miners in Orgreave in 1984. The Battle of Orgreave Archive (An Injury to One is an Injury to All) is an installation comprising objects, videos and archival material related to the events being re-enacted and the research that grounded it. Deller made use of different types of archival records, including the memories of those that had been involved in the violent clashes. In this way the work questions the power of the archive, and who gets to write history.

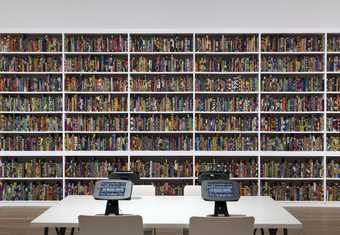

Other artists are creating archives as part of the artwork. These archives grow as the work is displayed. An example of this is Yinka Shonibare’s The British Library. This artwork is an installation of books covered in colourful ‘Dutch wax print’ fabric. The spines feature the names of first- or second-generation immigrants to Britain, who have made significant contributions to British culture and history. Each time the artwork is exhibited, visitors are invited to input their own experiences and stories of immigration into an accompanying website. Their responses are then archived and will provide a unique insight into changing perceptions and experiences of immigration over time.

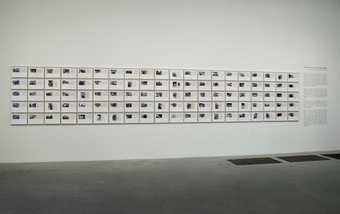

There also exists a form of artistic practice that speaks to the archive’s societal shift from passive guardian to active agent in holding collective memories. These works build on the power of the archive and create counter-narratives within these structures. We see this in the work of John Akomfrah and the Black Audio Film Collective, Susan Hiller’s J Street Project and From the Freud Museum and Atlas Group’s My Neck is Thinner than a Hair: Engines. Other works, like Richard Bell’s Embassy, actively build an archive into the work each time it is activated.