html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-html40/loose.dtd"

Eileen Agar and Paul Nash

Nash and Agar met in Swanage in 1935. Though both were in committed relationships, they became bound by their shared profession as Surrealist artists. Albeit brief, their love affair was intensely passionate. Nash’s parting letter to Agar read:

If we break now it is not because we are tired, we break at the peak of our flight where we have climbed dizzily like birds who make love in mid-air heedless of where they soar. We have not yet fallen down our bright sky, we only could not face the threat of the storm - O my bird my dear love.

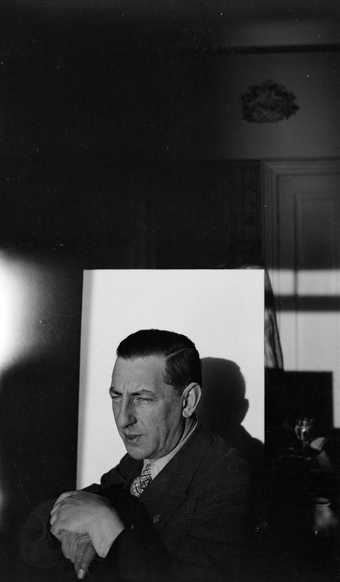

Photographer unknown

Black and white negative, Paul Nash inside New House, Rye, c1931–1934

Black and white negative

© reserved

View this item in Art & artists

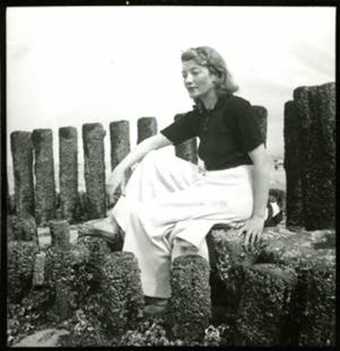

Photograph of Eileen Agar, c 1936

© Tate

Swanage offered many opportunities for the pair to explore and discover strange objects to inspire their work.

Digging like a child hunting for treasure, I unpebbled a long snakey monster with a bird’s beak. It was an old anchor chain, metamorphosed by the sea into a new creation, a snake bird.

Eileen’s ‘snakey monster’ gave birth to a number of collaborative works by the pair.

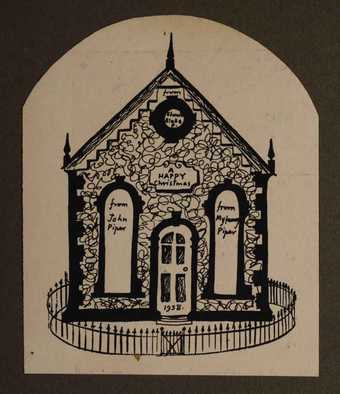

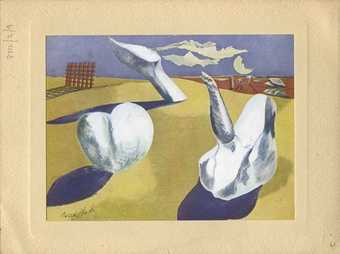

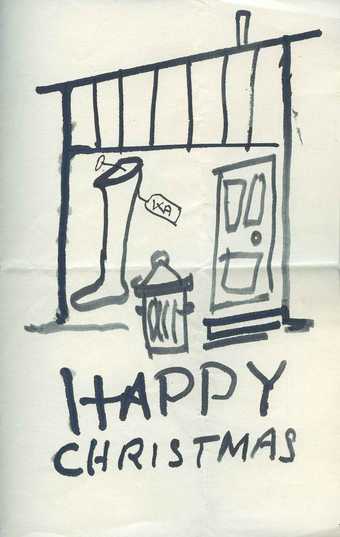

This Christmas card from Paul Nash and his wife Margaret (who knew about the affair) is potently reminiscent of the rocks and monsters of Swanage that dominated their work during this period. Explore more from Paul Nash’s archive or visit the Paul Nash exhibition at Tate Britain.

Christmas card from Paul and Margaret Nash to Eileen Agar with reproduction of ‘Nocturnal Landscape’ by Paul Nash

© Tate

Joan Moore and Kenneth Armitage

Kenneth Armitage met Joan Moore through a friend at the Slade. Although nine years his senior, they were both sculptors and held a deep mutual respect for one another which remained throughout their lives. Armitage proposed to Moore when he was serving in the war, based on the premise that he thought he was going to die and she could provide him with an anchor to normality. He didn’t die, but over six years had passed and they still had not experienced conjugal life.

So there was no real marriage at all. And I suppose in a way, although I was extremely fond of Jo, I never really felt I was married, because of that peculiar situation.

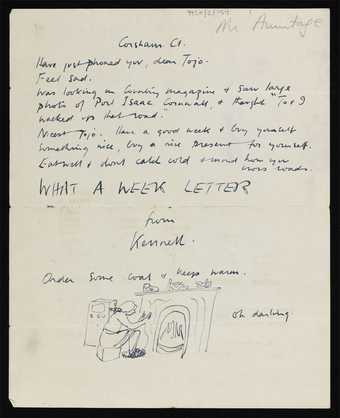

Letter from Kenneth Armitage to Joan Moore, addressed Corsham Court 1951

Ink on paper

TGA 9920/2/157

© The Kenneth Armitage Foundation

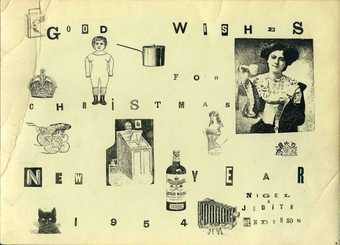

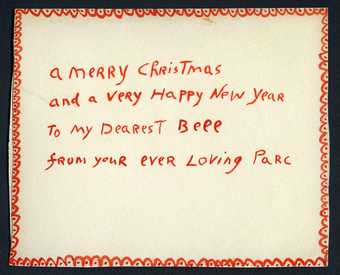

By the mid 1950s they had separated, but never divorced. Although Armitage had many relationships with other women, the two maintained a constant and affectionate correspondence. This Christmas card was sent in 1951, a year after their separation, and is one of the 299 letters from Armitage to Moore kept in the Tate Archive.

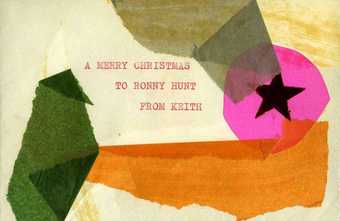

Christmas card created by Kenneth Armitage sent to Joan Moore in 1951

© The Kenneth Armitage Foundation

During a period when Moore was very sick, Armitage gravitated back to her:

Now she wasn’t well, and so I thought, all the lovely girls have gone and yet Jo is there and I do respect her enormously, and like her. I will now, for the rest of my life, be very nice to her. So I immediately did a lot, and every year I take her for a nice holiday, and I see her certainly every month… We’re great friends, and it’s very nice at my age to have someone I knew well 50 years ago.

It is clear from Armitage’s letters and his oral history by the British Library, that although their relationship was very unorthodox, Moore was in many ways his true life partner. Explore more from Kenneth Armitage’s archive.

Elizabeth Ramsden and Cecil Collins

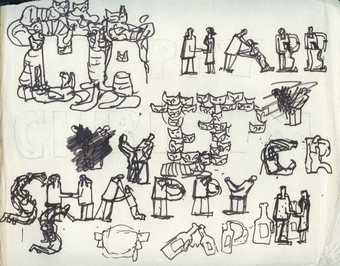

Cecil Collins met Elizabeth Ramsden while studying at the Royal College of Art. They married in 1931 and sustained a loving and supportive relationship, which is often implied through Collins’s artworks, as well as artefacts like this Christmas card. Here we see their nicknames for one another, Bell and Parc. According to a student of Collins’, Ramsden named Collins ‘Parc’, short for a loosely wrapped parcel, which according to Ramsden, was how he looked sometimes.

Christmas card from Cecil Collins to Elizabeth Collins, Cecil and his wife nicknamed each other Belland Parc respectively

© Tate

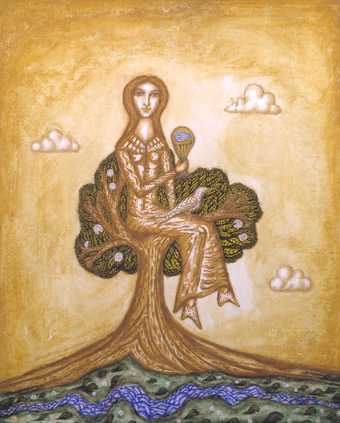

The message ‘To my Dearest Bell, from your loving Parc’ found in this Christmas note is also written on the back of his painting The Artist’s Wife Seated in a Tree. This portrait of Ramsden celebrates her femininity; the bird nesting beside her symbolises freedom, suggesting Collins’s respect for his wife’s autonomy. She often appears in his artworks in a similarly angelic form, or as the ‘anima’, representing inner life.

Cecil Collins

The Artist’s Wife Seated in a Tree (1976)

Tate

This second portrait of Ramsden and Collins, The Artist and His Wife also shows her as an equal and appears to rejoice in their marriage. The pair are seated at a table, the symbol of family meetings and ‘the exchange of foods on both physical and spiritual levels between the couple’. Judith Collins extends this metaphor to compare the table to an altar, with the ‘priests’ being Collins and his wife: a truly festive interpretation of this painting.

Cecil Collins

The Artist and his Wife (1939)

Tate

Tate Archive is the largest archive of British art in the world. For the first time, visitors can view highlights from this rich resource online alongside the Tate collection of artworks, seeing the inspiration and stories behind some of the greatest works of the past century. As part of opening up access to the Archive, Tate has also developed an online Albums feature which allows you to group together, annotate and share archive items and artworks.

Explore more from the Tate Archive.

Find out more about the Access and Archives project.

The Paul Nash exhibition is on at Tate Britain 26 October 2016 – 5 March 2017.