British School 16th Century

A Young Lady Aged 21, Possibly Helena Snakenborg, Later Marchioness of Northampton

1569

Oil paint on panel

632 x 482 mm

T00400

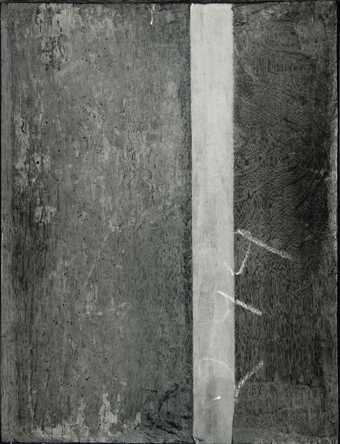

This painting is in oil paint on a wooden panel measuring 632 x 482 mm (fig.1). The panel made up of two boards of oak placed vertically and glued together at a butt joint, which runs just to the right of the sitter’s head (fig.2). X-radiography faintly reveals that two wooden dowels, each 6 or 7 mm diameter, were inserted into the boards at the joint to keep them in position until the glue had dried. The spacing of the dowels suggests that the panel may have been one of several cut from two, much longer planks that had been joined together beforehand. A much later strip of canvas is glued to the back of the joint to reinforce it (fig.3). The marks of the adze used to smooth the front surface of the planks are visible in raking light (fig.4). The X-radiograph also shows a triangular shape just above the sitter’s ear; it is probably an original insert into the wood to replace an imperfection such as a knot. The top and bottom edges of the joined panel are rough and splintery. This appears to be an original feature since the paint continues over some of the splintered texture. The back of the panel is bevelled unevenly on all edges.

The two boards are radially cut, though with some irregularity in the grain. Dendrochronological examination revealed that they are made of heartwood of eastern Baltic oak with sequences respectively between 1338–1533 and 1339–1543.1 The earliest felling date is probably 1551. The left plank was noted as being of typical width for eastern Baltic boards of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This suggests that the plank has not been trimmed significantly, thus giving weight to the hypothesised felling date. An incised ‘X’ mark on the back of the wider plank may be a cargo mark relating to the transit of the planks across the sea to England.

Fig.5

Cross-section through the red shadow in the costume below the sitter’s left hand, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: white chalk and glue ground, stained dark at the top from oil in the overlying priming; grey priming; opaque pink paint; white paint of embroidered decoration; thick, semi-translucent red glaze

Fig.6

The same cross-section photographed in ultraviolet light

The ground is white, about 20 to 150 microns thick (figs.5–6). Chalk was identified as the major component, bound in a glue medium. It thins out towards each edge, particularly the upper and lower where the wood is roughly cut. The ground layer is covered with a thin, pale grey, oil bound priming. It is 10 to 30 microns thick and is composed of lead white and chalk, with fine black, brown and opaque red particles to tint it. The streaky texture of the priming is apparent in the X-radiograph, running diagonally from left to right. It can also be seen in infrared reflectography (fig.7).

Fig.7

Infrared reflectograph of the hands, showing the streaky priming and the bold underdrawing

Infrared reflectography also reveals bold black underdrawing in the hands. A cross-section showed that this underdrawing was applied on top of the grey priming in brushed paint or ink. Surface stereomicroscopy revealed similar underdrawing in parts of the costume. In areas such as the hair and the folds of the sleeves, the dark paint or ink may have been applied as a wash rather than linearly. No underdrawing was visible in the face with any method of investigation. This may be explained by the density of the overlying paint layer or the use of a medium invisible in infrared.

Fig.8

Detail of the sitter’s right eye

Fig.9

Detail of the sitter’s left eye

Fig.10

Detail of the ruff, photographed at x8 magnification

Cross-sections and surface microscopy show that most of the painting was done wet-in-wet, with glazing, fine features and decorative details applied on top (figs.8–10). The palette includes lead white, black, vermilion, red lake, azurite, smalt, lead tin yellow and earth colours, all of which have a fine particle size.2 Chalk was found in many of the paint samples and its addition would have given the artist a more bodied paint without reducing the intensity of the colours. Along with a preference for bright colours and sharp contours, this artist was clearly interested in the surface texture of his painting.

For the face the artist took flesh tones mixed on the palette from lead white, vermilion, red lake, black and a yellow sienna earth and worked them together on the prepared panel with lively though small-scale brushwork (figs.11–12). While this paint was still wet, the artist took a fine brush and painted in the fine brownish lines of the eyebrows along with some sgrafitto work to depict the texture (figs.13–14). For the blue veins of the face he mixed azurite into a flesh tone and again worked into the wet paint on the panel (fig.15). Smalt and possibly azurite were mixed with lead white for the whites of the eyes. An interesting subtlety in the use of pigments can be seen at high magnification in the hands: here the blue veins were done with smalt rather than azurite; the latter pigment was expensive.

Fig.15

Wet-in-wet application of azurite into flesh paint for the veins in the temple, photographed at x12 magnification

The fabric of the sleeves was painted with white and grey tones wet-in-wet, using the turbid medium effect to denote the folds in the shadows by applying a thin scumble of grey paint over the black underdrawing (fig.16).3 The artist built up the white highlights in thick paint, which holds the texture of the brush. The green floral design was applied over the modelled fabric. The leaves appear to have been laid in with a transparent brown paint, or possibly a copper green that has become discoloured (fig.17).

Fig.16

Detail of the sleeve, photographed at x8 magnification

Fig.17

Green brushwork in blouse, photographed at x10 magnification

They were then built up with thick green tones composed of azurite, blue verditer, yellow lake, chalk, smalt, sienna and black. It is possible that the blue verditer (artificial azurite) was included as a cheap extender of the more expensive mineral pigment. Some of the leaves appear to have been at least partially glazed with translucent green paint containing yellow lake, a copper green and black. In many areas this green has faded or become brown. Orpiment was identified in the green feather in the sitter’s hat, mixed with azurite and lead tin yellow.

Fig.18

Detail of the red costume, photographed at x10 magnification

The red dress was constructed wet-in-wet with tones mixed from lead white, vermilion, red lake, chalk, gypsum and black. When dry these areas were glazed with translucent red lake mixed with chalk (fig.18). This red lake glaze has faded very slightly except where protected from light by the rebate of the frame. Paint to depict the embroidery was applied thickly on top of the glazed areas (fig.19). The colours were mixed from lead tin yellow, vermilion and lead white, and were applied sequentially one on top of the other.

Fig.19

Embroidery on the bodice, photographed at x10 magnification

A similar sequential build-up is visible in the sitter’s jewellery, where red lake, azurite and black were used alternately to denote rubies, sapphires, enamel work and diamonds. The pearls were all depicted in grey tones followed by white and yellow impastoed highlights (fig.20).

Fig.20

Pearls on the jewel hanging from the ribbon around her neck, photographed at x10 magnification

The grey ribbon holding the jewel around the sitter’s neck is composed of smalt, possibly with a very small addition of azurite visible in the bluest highlights. The smalt has degraded, leaving the paint looking pale grey and brown in areas where it should have been blue. In addition to the loss of colour, the thick application of this paint has created a pronounced pattern of drying cracks in the paint, which has picked up dirt. By contrast, the greyish blue shadow cast by the ribbon does not appear to have discoloured and seems to be an optical blue made from black and white.

The background that we can see is not original, apart from the inscriptions. Microscopic examination reveals that the original black background has suffered very bad abrasion. The repainting appears to date from shortly before the painting’s acquisition by Tate in 1961.

May 2005