Fig.1

Jan Siberechts 1627–c.1703

View of a House and its Estate in Belsize, Middlesex

1696

Oil paint on canvas

1080 x 1393 mm

T06996

This painting is in oil on canvas measuring1080 x 1393 mm (fig.1). The linen canvas is plain woven and it was given a thick coat of animal-glue size before being primed for painting. Examination of the tacking edges suggests that the picture was laced into a temporary loom for priming and painting, a common though not invariable practice amongst Netherlandish painters in the seventeenth century. Both the priming and the paint layer extend over onto the tacking edges and in the narrow unpainted perimeter of canvas beyond them there are regularly spaced, sharply ‘pulled’ holes where the lacing exerted its tension. When completed, the painting would have been unlaced and nailed onto a wooden strainer, which has not survived.

The double ground has a brown first coat consisting of earth colours, umbers, black, lead white, ground glass and fine sand bound in oil (figs.2–3).1 The second layer, also bound in oil, is a light tan colour formed from a mixture of lead white, yellow and red ochres, calcite, ground glass and fine sand. The presence of silica in the form of powdered quartz or sand has been found in some of Rembrandt’s grounds, and was likely known throughout the Low Countries when the artist required a hard ground that would absorb little oil from the paint. Used in very coarse qualities the sand could also provide texture, though in this instance its moderate particle size probably just gave a degree of ‘tooth’ to the painter’s brush.

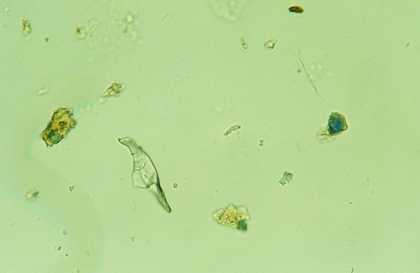

Fig.2

Cross-section from the sky, photographed at x250 magnification. From the bottom: lower layer of ground made from earth colours, umbers, black, glass and sand; upper layer of ground made of lead white, earth colours, ground glass and fine sand; off-white underpainting made from lead white, yellow ochre, black and ground glass, which can be seen as dark particles; blue made from ultramarine and lead white

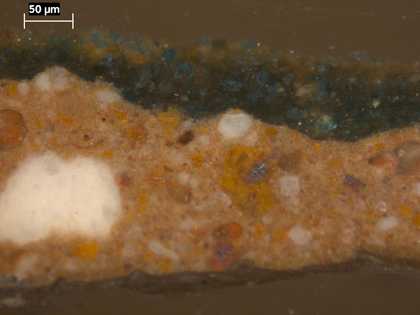

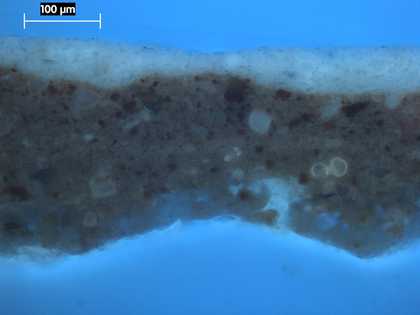

Fig.3

Cross-section from the sky, photographed at x250 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: lower layer of ground made from earth colours, umbers, black, glass and sand; upper layer of ground made of lead white, earth colours, ground glass and fine sand; off-white underpainting made from lead white, yellow ochre, black and ground glass, which can be seen as dark particles; blue made from ultramarine and lead white

The first stage in making the composition would have been the underdrawing but we do not know what sort of materials Siberechts used in this instance; no lines are visible with either microscopic or infrared examination, although this need not mean they are absent. The paint layers are very dense and an underdrawing in say brown or red would be difficult to detect against the tan ground. A number of pen and watercolour topographical drawings by Siberechts exist and, although none relates to this painting, it is possible that he might have done one of this view in preparation for the oil painting.2 That there would have been at least an elementary underdrawing on the prepared canvas is indicated by the precise way of painting this complex composition (there are no pentimenti for example), and by the method he used to create the effect of aerial perspective in the most distant hills.

The first stage of painting was the underpainting of the sky, where Siberechts blocked out the dark priming with a thick layer of off-white paint to provide a reflective ground for his blue (figs.2–3). This underlayer does not end at the horizon but lower down the composition at the base of the furthest range of hills, its light tone emphasising their hazy blue distance. This feature is found in other similar British landscapes by Siberechts, for example View of Longleat in a private collection. The off-white underpainting in the sky of Tate’s painting is composed of lead white mixed up with a large quantity of glassy particles, some pipeclay and small amounts of yellow ochre and black. The glass is easily visible in a cross section (fig.2).

The technique used thereafter is consistent throughout the picture; the colours, which are mostly opaque, were mixed up on the palette and applied wet in wet with no preparatory underpainting. Large areas were blocked in before tonal or figurative details were added on top (figs.4–5) and in each element of the picture dark tones were put on before light. Glazes are present here and there in the trees but as local patches rather than large passages. The tan ground is hardly ever left visible as a tonal element in the composition nor does it contribute much through reflective powers to the intensity of the colours in this painting. For this quality the artist has relied on the type and mixtures of pigments. It is worth examining this feature in some detail, as the choice and mixtures of pigments illustrate much about the sophisticated training a continental artist such as Siberechts would have received and also, indirectly, about the status of the person who commissioned and paid for this painting. The sky is composed of lead white with very good quality ultramarine and a small number of colourless glassy particles (fig.2). For the bluish green foliage in the far distance beyond the grove of trees surrounding the house, he mixed what appears to be a less intensely coloured (and therefore less expensive) ultramarine with green earth, yellow ochre, sienna, black, lead white, pipeclay and glassy particles. All the dark greens found in the trees over the rest of the picture have instead of ultramarine the mineral pigment azurite, mixed with varying quantities of green earth (two types appear to have been chosen, one bluish green, the other yellowish green), yellow and red ochres and siennas, black and glassy particles. For semi-translucent top glazes he added brown pink and for the lighter, yellowish green strokes in the trees he mixed in large quantities of the bright opaque pigment, lead tin yellow. The creamy-yellow clouds, brushed wet-in-wet into the blue sky, are mixtures of lead white, lead tin yellow and glass. A consistent feature throughout these mixtures is the large size of the particles, especially the green earth, azurite, lead tin yellow, black and red ochre (figs.4–7).

The first point to note about the paint mixtures is the high quality of the pigments. Ultramarine and azurite are both minerals of comparatively high tinting strength and very high cost, especially ultramarine. During this period opaque greens used in oil painting were very often made from optical mixtures, as, apart from verdigris, there was no single green pigment that could combine the required tinting strength with the ability to resist fading from exposure to light. Verdigris, though it has proved stable in many paintings, was known to be fugitive in some circumstances and troublesome when mixed with certain other pigments.3 Green earth is very stable but it is not a strong colour when used in oil. Of the blues available to vary and intensify it, Siberechts chose the brightest, the most durable and the most expensive. Their very different hues (ultramarine is the bluest of blues whereas azurite has a greenish cast) ensured a variety of tones, a factor he exploited in a subtle way when using ultramarine for the most distant greens. Receding orthogonals may be the principal device for the perspective of the house and its gardens but the ultimate sense of space and great distance comes from this use of a cool blue for the sky, hills and foliage in the wide expanses beyond.

Siberechts had become a master in the powerful Guild of St. Luke at Antwerp by 1648. In order to qualify for this he would have had to undergo several years of training in the studio of an established painter. We do not know which one it was but this mastery over pigments – their comparative hues, tinting strengths, durability and optimum particle size – was one of the benefits to be drawn from the years spent serving a master. The use of ground glass in paint is a characteristic of some artists trained in the Netherlandish, Italian and Spanish traditions.4 It has been found in some of Rembrandt’s browns5 and most notably in the ‘tonal’ landscapes of Jan van Goyen and Salomon van Ruisdael.6 Gheeraert’s Captain Thomas Lee (Tate T03028) contains it, as do areas in a set of portraits by the Dutch sixteenth-century painter, Cornelis Ketel.7 In some instances the glass may actually be pale or discoloured smalt, a glassy blue pigment. In this painting, however, it appears to be simply glass; there is no blue colouration in it and none of the samples showed the presence of the metallic elements associated with smalt. In terms of the reasons for use there would have been two advantages in choosing either one – glass or pale smalt. As a bulking agent they would thicken the paint without obscuring the bright (and expensive) pigments and, being rich in lead or cobalt, they would act as a siccative in mixtures containing colours that dried slowly in oil, green earth for example. This is the reason given for its use in the manuals of painting. Marshall Smith, in his book The Art of Painting, which was first published in 1692, says ‘For your Powder-Glass, take the Whitest Glass, beat it very fine in a Morter, and grind it in water to an Impalpable powder; being thoroughly dry, it will dry all Colours without drying Oyle, and not in the least Tinge the purest Colours, as White, Ultramarine, etc.’8 In this painting, however, its presence in such mixtures as lead white with lead tin yellow, both excellent driers, suggests that its use as a bulking agent was equally important.

Siberechts, then, was a soundly trained technician who, with this painting, was fortunate in finding a patron who could afford the best. Partly as a consequence, it is in very good condition. There has been no fading and it looks as if the recent lining (done sometime before the painting was acquired by the Tate in 1995) is the first it has had. The original varnish, long since removed and replaced with newer, would probably have been mastic in an organic solvent.

July 2016