Fig.1

David des Granges (1611 or 13 – ?1675)

The Saltonstall Family c.1640

Tate

T02020

Fig.2

Detail of The Saltonstall Family c.1640, showing the second wife and mother, and her baby

Fig.3

Detail of The Saltonstall Family c.1640, showing the father and the tapestry background

Fig.4

Detail of The Saltonstall Family c.1640, showing the two older children

This painting is in oil on canvas measuring 2140 x 2762 mm (figs.1–4). The support is made from three pieces of canvas stitched together as shown in the diagram below:

Fig.5

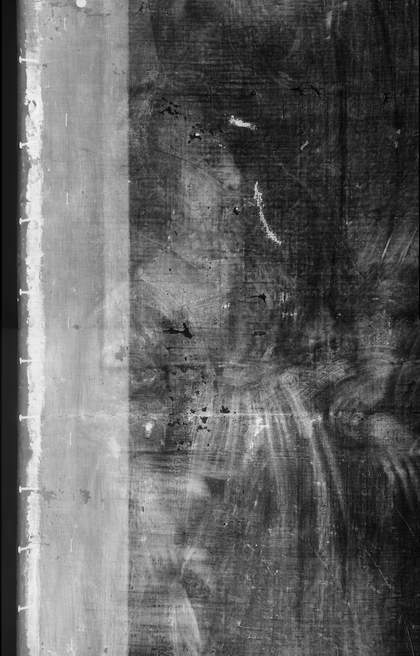

X-radiograph of the man’s head and the old losses of paint along the top edge

Fig.6

X-radiograph of the child at the left edge

Fig.7

X-radiograph of the second wife and mother with her baby

The two large pieces are plain woven and have selvedges running along the top and bottom of each piece. Both have 14 vertical threads and 16 horizontal per square centimetre (figs.5–7) and are 1080 mm wide from join to selvedge. The smallest piece, a rectangular section at the top left corner, has a coarse herringbone weave; despite the difference in weave, this piece has every appearance of being an original part of the painting, rather than a later replacement for a damaged original section. The painting’s four tacking edges are present. The paint extends beyond the turnover at the top and left edges, indicating that the painting was originally larger in those directions. At some point in its history, the painting was attached to a smaller stretcher, causing considerable loss of paint. Fig.5, an X-radiograph of the father’s head and the top edge, shows this loss of paint in a broad band parallel with the top edge: this band is continuous across the painting and a similar band of paint loss is present across the bottom edge, 50mm above the turnover. When the Tate acquired the painting in the 1970s, the painting was placed onto a larger stretcher that reinstated these areas into the picture plane.

Fig.8

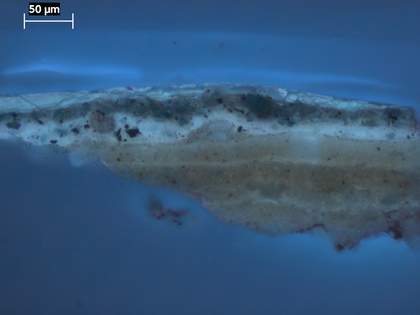

Cross-section taken from the dark green foliage of the tree in the tapestry near the top right corner, 175mm from the right turnover edge and 344mm from the top. Photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom to the top: trace of glue-size priming on the canvas, partially stained deep crimson with acid fuchsin to indicate the protein-containing size layer; chalky, off-white ground, probably applied in two coats; beige priming; thin, sketchily applied mushroom-brown paint; white and blue paint worked wet-in-wet for the sky of the tapestry; green paint of the foliage in the tapestry; natural resin varnish

Fig.9

The same cross-section as shown in fig.8, photographed in ultraviolet light at x320 magnification

Fig.10

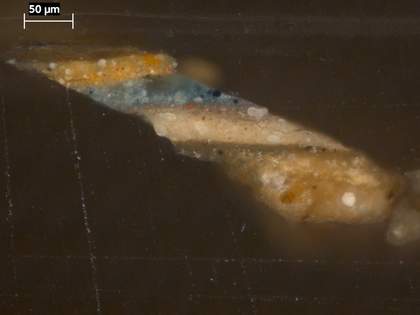

Cross-section through the yellow and blue border of the tapestry at the left edge, from the herringbone-weave piece of canvas, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom upwards: fragment of chalky, off-white ground; beige priming; thin, sketchily applied mushroom-brown paint; blue paint; yellow paint; varnish

Fig.11

The same cross-section as shown in fig.10, photographed in ultraviolet light at x320 magnification

Fig.12

Detail at x8 magnification of the mushroom brown underpaint in the sky of the tapestry, as shown in cross-section in figs.8–11

Fig.13

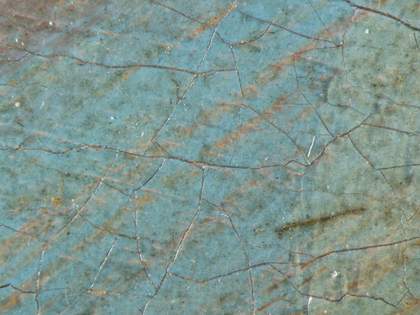

Detail at x8 magnification of the carpet in reflected light, showing the streaky texture of the underlying priming

The ground is composed of a dull off-white, chalk-rich layer bound in oil and seemingly applied in two coats (figs.8–11). The priming on top of the ground is opaque pale beige (fig.12); it was applied with a streaky texture, as shown in fig.13. The ground and priming have suffered a great deal of cracking and loss due to poor adhesion to the support, particularly along the edges described above.

Fig.14

Detail from infrared reflectogram of the faces of the two wives and the baby, showing brushed underdrawing

Fig.15

Detail from infrared reflectogram of the two children in the left of the composition, showing brushed underdrawing

Fig.16

Detail from infrared reflectogram of the father’s head, showing brushed underdrawing and a change to the angle of the hat brim

Fig.17

Detail from infrared reflectogram of the father’s left arm and hand, showing brushed underdrawing

Fig.18

Dark drawing line visible beneath the boy’s left cuff, photographed at x8 magnification

Infrared reflectography together with close examination of the paint surface reveal linear black underdrawing applied broadly with a brush (figs.14–18).

Fig.19

Cross-section taken from the red fringe of the bed. Photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom upwards: chalky, off-white ground, probably applied in two coats; beige priming; opaque dark red of bed hanging; opaque orangey red of fringing; varnish

Fig.20

The same cross-section as in fig.16, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.21

Photomicrograph at x32 magnification of a tiny paint loss in the red bed hanging, with darker red underpainting visible in a thin line at the left edge of the paint loss

Fig.22

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the little girl’s dress, showing white decorative patterning applied on top of opaque red paint, which would have been dry when the white was applied

Two basic techniques of painting are discernible in the painting; additive work and wet-in-wet painting. Cross-sections from and surface microscopy of the costumes, carpet, tapestry and drapery reveal an additive technique with a general lay-in of plain colour overlaid when dry with folds and decorative details. For example, the red bed hangings were first painted dark red, after which lighter, brighter reds were applied on top for the folds (figs.19–21). Similarly the little girl’s red dress was laid in with two shades of opaque red paint, followed when dry with white and pink opaque decorative detail (fig.22). It is not entirely clear whether translucent red glazes would have been applied in addition to the opaque reds. If there were, they are not now present for certain either in close examination of the paint surface or in cross-section. On the other hand, there is translucent red lake pigment present in addition to opaque vermilion in the opaque red paint; this would have given a depth of tone to the brighter red vermilion pigment.

Fig.23

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the father’s left eye

Fig.24

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the father’s right eye

Fig.25

Microphotograph at x8 magnification of the little girl’s right eye

Fig.26

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the second wife’s pearls

The faces and flesh tones of all the figures were done in a wet-in-wet technique (figs.22–26). Pigments apart from those mentioned are lead white, indigo, smalt, azurite, yellow ochre and other earth pigments including umber, black and orpiment.1 They were used together selectively in mixtures to form the colours we see in the painting.

Fig.27

Microphotograph at x16 magnification of the father’s black hat, showing very small-scale drying cracking

Apart from the old paint losses and cracking described above, the painting is in good condition. A few black areas have developed very small systems of drying cracks, perhaps indicating the use of siccatives in the oil (fig.27).

March 2021