Fig.1

Marcus Gheeraerts II 1561 or 2‒1636

Portrait of a Woman in Red 1620

Oil paint on panel

1142 x 902 mm

T03456

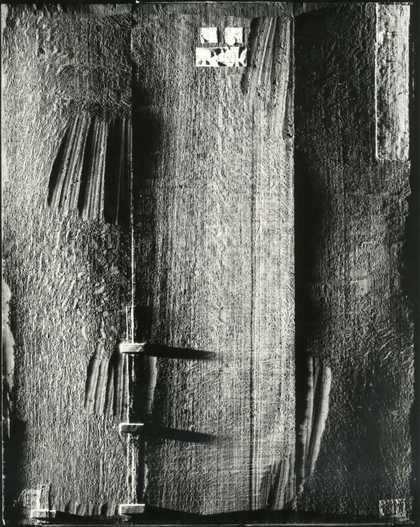

This painting is in oil paint on an oak panel measuring 1142 x 902 mm (fig.1). At its bevelled edges the panel is approximately 4 mm thick. It is composed of three roughly cut boards of Baltic oak, from left to right respectively 261, 353 and 261 mm wide; they were placed edge to edge vertically and glued together at butt joints (figs.2–3). Dendrochronology revealed that the three planks are from the same small woodland locality within the Baltic area, with the two outer planks being from the same tree.1 The probable earliest felling date of all three is 1609. The central plank bears very close similarity to a plank in a painting of the same year by the artist Cornelius Johnson (Portrait of Susanna Temple, later Lady Lister, 1620, T03250). It is possibly from the same tree, making this either a fortuitous usage of boards from one shipment from the Baltic or the employment of the same panel maker in London by these two artists.

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Portrait of a Woman in Red

Fig.3

The back of Portrait of a Woman in Red, photographed in black and white with raking light from the left

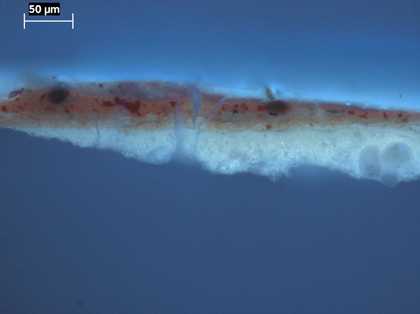

The ground is off-white, about 80 microns thick and made up of chalk mixed with a little black and brown ochre and bound together in animal glue (fig.4). Its surface is smooth and it is in good condition apart from a few old, restored losses in the lower centre of the portrait and along the lower edge. The ground laps over the top and bottom edges of the panel support, indicating that we have the full original height of the painting. It is not possible to say whether the absence of overlap on the upright sides means that the painting has been reduced in width.

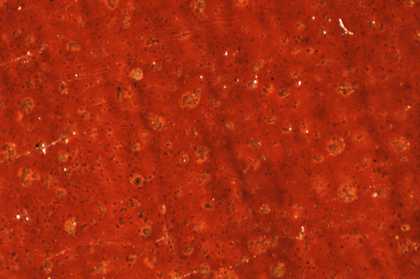

Fig.4

Cross-section through the red curtain at the top edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: white ground; salmon pink priming; semi-translucent dark red wash of paint to lay in the general shape; bright, opaque red paint; translucent crimson glaze; varnish

Fig.5

The same cross-section viewed in ultraviolet light

The priming is opaque salmon-pink colour, about 25 microns thick and composed of lead white, chalk, red ochre, yellow ochre, red lake and black mixed together in oil (figs.4–5).2 It plays an important part in the painting, providing the overall warm tone, the rosy glow in the face and the illusion of skin beneath the thin paint describing the fine linen kerchief and cuffs.

No drawing is visible in the face with any method of examination. Perhaps it exists very faintly beneath the priming, which being reddish in colour would impede infrared examination – but none of the Gheeraerts portraits at Tate display underdrawing, whatever the colour of the priming. In this respect they differ from his Portrait of the Earl of Essex at Trinity College Cambridge, whose face has an elaborate, firm linear drawing that is discernible with the unaided eye. It has been suggested that this drawing might have been traced from a template kept in stock for the many portraits that Gheeraerts produced for Essex.3

Fig.6

Detail of the face and collar

While the face was painted wet-in-wet in thin flesh-tones that allow the underlying salmon pink colour of the priming to glow through (fig.6), the curtains, chair, background and costume were built up in a system of orderly layers, a system used in all Gheeraerts’s panel paintings at Tate.4 Thin, translucent underpainting in these areas was followed when dry with bright opaque paint, decorative detail and rich translucent glazes (seen in fig.4, for example). The folds of the curtain were described with opaque tones of rich reddish orange, mixed from vermilion with some red, yellow and orange lake pigments and chalk. With time it has developed lead soap aggregates (fig.7).5 The glaze of madder on top of this opaque paint has faded except where protected from light by the rebate of the frame (fig.8). A similar system was adopted in the skirt, with a final addition of a thin, broken layer of lead white for the white linen apron (fig.9).

The dark plum coloured background was built up with successive tones produced from complex mixtures of pigments including madder lake, a yellowish brown lake, lead white, ochres, glassy particles, gypsum and ivory or bone black (figs.10–11). Finally this paint was given a glaze of rich crimson; again it has faded somewhat in areas not protected by the frame. When viewed in cross-section under ultraviolet light, all the glazes in the painting fluoresce in a way that indicates an oleo-resinous medium.

Fig.10

Cross-section through the dark, plum-coloured background at the top edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: white ground; salmon pink priming; very thin, semi-opaque white paint; brown opaque paint; very dark brown opaque paint; brown opaque paint; translucent crimson glaze of paint

Fig.11

The same cross-section viewed in ultraviolet light

The varnish is modern, probably dating from the years shortly before the painting was acquired by Tate in 1982. The painting has had no major treatment since then. Non-original canvas strips and wooden buttons help support the back of the original joins, which, from the absence of significant paint loss at the equivalent areas on the front of the painting, do not appear ever to have parted company.

May 2004