Hans Eworth active 1540–1573

Portrait of an Unknown Lady 1565–8

Oil paint on panel

998 x 619 mm

T03896

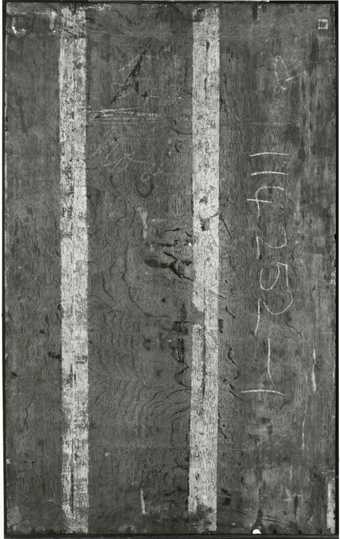

This painting is in oil paint on a wooden panel measuring 998 x 619 mm. The panel is composed of three radially cut boards of oak, which were placed side-by-side vertically and glued together at butt joints (figs.2–3). Dendrochronological examination revealed that the wood is from the Baltic area with a felling date between 1546 and the late 1550s.1 Originally the boards would have been of roughly similar width but a strip of wood about 75mm wide was removed from the outer edge of the right board some time before 1866; we have no information why.2

Fig.2

The back of the panel, photographed in black and white

Fig.3

X-radiograph of Portrait of an Unknown Lady, 1565–8

The white ground is composed of marine chalk and animal glue.3 It is around 150 microns thick. It is covered over with thin (10–20 microns), very pale grey priming, which was applied in a streaky fashion (figs.4–5). In cross-section the priming appears as a bright opaque white matrix containing yellow earth colours and finely ground opaque red and black particles. In reality, however, its thin application would have ensured a translucency that allowed the underdrawing on the white ground to remain visible to the artist.

Fig.4

Cross-section through the patterned skirt at the lower edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: chalk ground; pale grey priming; thin, streaky, mushroom coloured underpaint; opaque white patterning of skirt; semi-translucent red glaze; varnish

Fig.5

Cross-section through the patterned skirt at the lower edge, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: chalk ground; pale grey priming; ; thin, streaky, mushroom coloured underpaint; opaque white patterning of skirt; semi-translucent red glaze; varnish

Infrared reflectography (figs.6–8) reveals bold continuous outline drawing of the face with short, broken lines marking the features. There are curled dashes at the hairline and light, parallel shading lines in the face, these latter applied freehand.

The background was underpainted with thin, mushroom brown paint (figs.9–10), with a small shield-shaped reserve for a coat of arms left unpainted in the upper left. The artist went on to cover up this reserve with the dark semi-translucent paint he used for the final painting of the background and there is no evidence that any coat of arms existed before the cartouche that we can see.

Fig.9

Cross-section through the yellow inscription on the brown background, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: sliver of chalk ground with a pink stain from acid fuchsin; pale grey priming; dark, mushroom coloured underpaint; dark brown paint of background; yellow paint of inscription

Fig.10

Cross-section through the yellow inscription on the brown background, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: sliver of chalk ground with a pink stain from acid fuchsin; pale grey priming; dark, mushroom coloured underpaint; dark brown paint of background; yellow paint of inscription

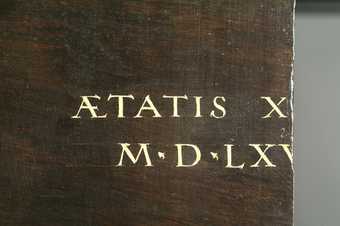

The multi-directional brushstrokes used to apply the dark background paint are visible on the surface (fig.11). Analysis with gas chromatography of the binding medium of this paint, incorporating a small fragment of the yellow inscription, suggested linseed oil for the background and either heat treated linseed oil or an egg-oil emulsion for the yellow.4 Either of the last two binding media would have helped produce paint that flowed desirably during application but stayed put once applied.

Fig.11

Detail of the background inscription, showing streakily applied dark brown paint that allows the paler underpaint to show through. Tramlines have been scored into the background paint to facilitate the painting of the inscription

For the face and flesh tones the artist worked with wet-in-wet blending techniques, using the delicate tones that characterise his work (figs.12–19). The paint is and always would have been extremely thin but with the natural tendency of oil paint to become more translucent with age, the underdrawing is now more visible than it would have been originally.

The costume, by contrast, was painted in an additive technique in which the form and its detail are built up in a multilayered system. The highlit areas of the dress were first painted opaque white, the shadowed areas pale mushroom colour (figs.4, 20).

Fig.20

Cross-section through the patterned dress, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: pale grey priming; opaque white underpaint of clothing; translucent red glaze; thin, opaque grey patterning; opaque yellow patterning

When dry, these areas were glazed with red lake, after which all the patterning was applied (figs.21–23).

An unfaded strip of paint, which has been protected from light by the frame along the bottom of the painting, shows that the pearl-studded dress was originally a much deeper shade of red (fig.21).5

Fig.21

Detail of the dress at the lower edge where it has been protected from light by the frame. Unfaded red glaze and applied patterning on top of it

Fig.22

Detail of the patterning of the dress and the cameo brooch

Fig.23

Detail of the hair and the red cap

A detail of the plumes of the hat and surrounding areas (fig.24), shows the sequence in which the different areas were painted. The elaborate, painted coat of arms in the background is a later addition.

Fig.24

Detail of the plumes on the hat. It shows that the black hat was painted first on top of the mushroom brown underpaint of the background, leaving a reserve for the plumes. The plumes were painted in white, pink and lilac-grey coloured paint, applied wet-in-wet. The jewels were put in with an additive technique before, last of all, the dark background paint was brought up to the boundary of the hat, leaving the mushroom coloured underpaint visible at its edges.

When the painting was cleaned and restored at Tate in 1985, a new oak board was cut to replace the one that was removed before 1866. The new board was painted to match the background but no attempt was made to recreate the missing inscription. It was placed into the frame so that it lies adjacent to the panel but it is not attached to it with adhesive.6

July 2003