Fig.1

Cornelius Johnson 1593–1661

Portrait of Susanna Temple, later Lady Lister

1620

Oil paint on panel

678 x 515 mm

T03250

The painting is in oil on an oak panel measuring 678 x 316 mm (fig.1). The panel is composed of three vertical boards glued together at butt joins (fig.2). At 310mm wide, the central board is substantially larger than the two outer boards: the right is 142 mm wide and the left, 62 mm. All three boards taper down to a slightly lesser width at the bottom. The panel has been thinned and fitted with a pine cradle at some point in the past; as a consequence information about its original thickness has been lost.1 The cradle was modified in 1981 to reduce the tension it exerted on the panel, which was creating a washboard effect. Since this treatment the panel appears stable. The X-radiograph shows two old, repaired splits and several minor checks along the top edge. There is some evidence of past woodworm attack. The X-radiograph also showed horizontal incisions on the face of the panel, almost at 90 degrees to the wood grain, which are probably the marks of a tool. The presence of paint and ground on the edges of the panel confirms that its dimensions are original.

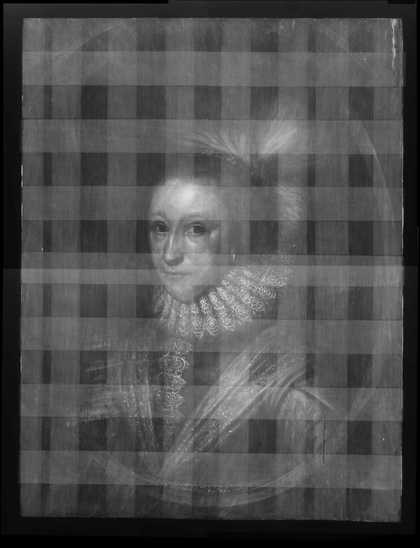

Fig.2

X-radiograph of the whole painting. The rectilinear lattice is the image of the cradle.

Dendrochronology in 2004 determined that the wood is of Baltic origin, with an earliest possible felling date of 1609 for the central board.2 The width of this board is similar to other eastern Baltic boards found in sixteenth and seventeenth century panels. It was noted that there is a very strong match between the wood of this painting and that of Marcus Gheeraerts II’s Woman in Red also of 1620 (T03456). This indication that both artists were using boards derived from trees located within the same relatively small area of woodland suggests they were using a common panel maker.

Fig.3

Cross-section through the feigned oval frame at the bottom of the picture, photographed at x 320 magnification. From bottom to top: white ground; grey priming; paint of feigned oval frame; synthetic resin varnish

Fig.4

Detail at x8 magnification of decoration in the headdress. The near vertical streaks are the marks of the blade that was used to smooth the ground layer. The grey, nearly horizontal streaks running underneath the red and yellow detailing are in the priming layer.

The ground is white, composed of chalk with traces of bone black, bound together in animal glue. It was applied thickly (110–190 microns) to fill the grain and give an even surface. The ground is covered over with a coat of oil bound, grey priming which was applied thinly (10–15 microns) and in a streaky fashion (figs.3–4). It contains lead white with black and fine opaque red particles. The streakiness is visible in the X-radiograph as long strokes angled at about 45 degrees in the area of the trompe l’oeil frame and variously through the sitter’s costume (fig.2).

Most of the composition was executed wet-in-wet with thin, opaque colours, followed by subsequent glazing and the picking out of details. The background and figure were painted before the feigned oval surrounding them; a reserve was left for this feature during the painting of the figure. In general the paint was applied thinly and smoothly, although when it is viewed closely the brushwork is animated and expressive (figs.5–9).

The paint is thicker and more bodied in the feathers and the mid-tone green of the costume decoration (fig.10). Impasto is confined to the detailing on the lace and jewels (figs.11–13). Originally the black costume was red. Examination through the microscope reveals that it was finished, as glazes of lake lie over the opaque body colour (fig.14). In the X-radiograph bows and other brushwork can be seen, which relate to this earlier design. The change to black was done by the artist rather than by a later hand; the paint of the trompe l’oeil frame extends over the edges of both the black and the underlying red costumes. It is possible that this change was made in relation to the death of Queen Anne in 1619.

Sampling of pigments was limited to the edges of the painting or to the few old damages within the composition. The opaque dun colour of the trompe l’oeil border contains lead white, chalk, verdigris, black, vermilion, glassy particles and probably a yellow lake. The green sash contains similar minus the vermilion. The flesh tones appear to be lead white with vermilion, red lake and black, plus azurite in the lightest cool tones. This blue pigment also appears mixed with lead white for the whites of the eyes (figs.15–16).

Fig.15

Detail at x8 magnification of the sitter’s right eye

Fig.16

Detail at x20 magnification of the blue pigment in the eyeball of the sitter’s right eye

Fig.17

Inscription, lower right corner

Several layers of old, natural resin varnish were removed in 1981 and the painting was revarnished in a modern synthetic resin.

2005