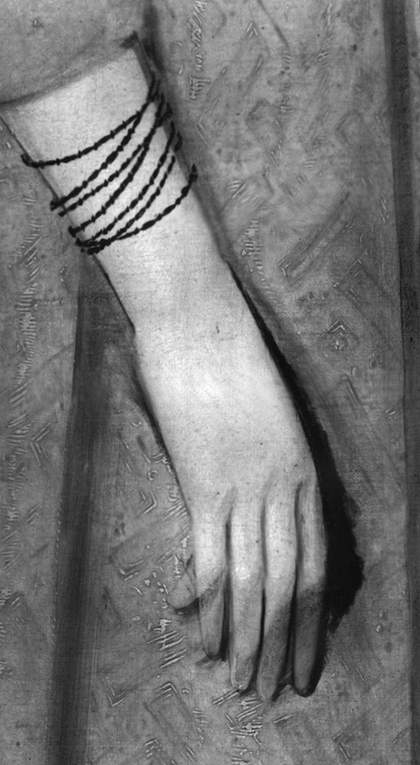

Fig.1

British School 17th Century

Portrait of Gertrude Sadler c.1620–23

Tate

T03030

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Portrait of Gertrude Sadler c.1620–23

This painting is in oil paint on a single piece of plain woven canvas measuring 2250 x 1335 mm (fig.1). The canvas is now lined with glue composition adhesive onto a stiff, open weave canvas; this appears to date from the early twentieth century. This lining canvas, which has an opaque priming on its reverse side, dominates the X-radiograph, masking the nature of original threads (fig.2). Cusping of the original canvas, however, is evident in raking light on all four edges of the painting.1 At the time of lining the painting was mounted on a larger stretcher, and the unpainted margin left visible was filled and retouched to match the original.

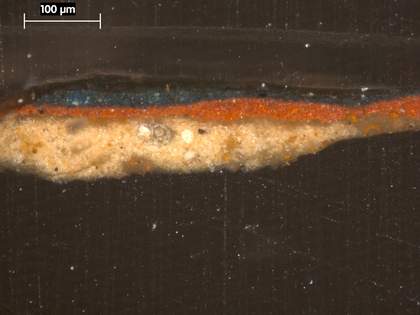

Fig.3

Cross-section taken from the unfaded area of red curtain at the left edge, 615 mm from the top edge of stretcher, photographed at x250 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: off-white ground, average thickness 100 microns, composed of marine chalk, lead white, red lead, umber, Cologne earth and bone black all bound together in oil; probably a layer of pure oil to seal the chalk rich ground; opaque red of curtain, average thickness 25 microns, composed of vermilion with black, red lake and yellow; translucent crimson glaze, average thickness 10 microns, composed of red lake with a little vermilion; varnish and dirt

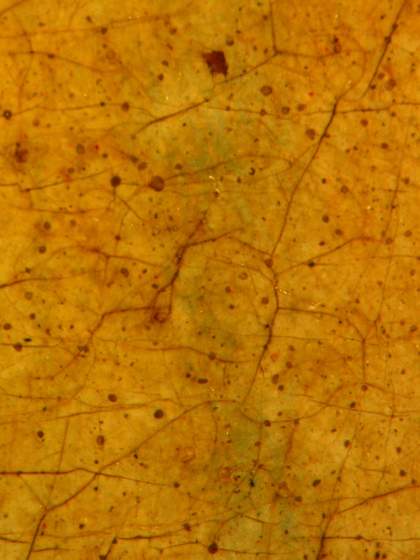

Fig.4

The same sample as in fig.3 photographed at x250 magnification in ultraviolet light

The ground is off-white and is composed of lead white, chalk and a small addition of earth colours bound together in oil (figs.3–4). Though red lead was visible in the ground layer when it was examined in dispersion with polarised light microscopy, it was not clear whether this was a deliberate addition by the artist or had developed as a later formation from the lead soap aggregates that are present in many areas of the painting. The cross-section (fig.3) suggests that the red lead has developed, since it manifests in cross-section as circular spots or rings, which represent spherical spots like the aggregates. The cross-section also shows a thin, translucent, unpigmented layer that does not fluoresce in ultraviolet light, which suggests it is a coat of oil applied to seal the chalk-rich ground.

Fig.5

The sitter’s left hand in infrared reflectography

Fig.6

The sitter’s right hand in infrared reflectography

Thin, linear underdrawing is visible with infrared reflectography in the hands (figs.5–6). In the light of the other version of this painting now in the National Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide (see curatorial entry), it may be very significant that there appear to be two pentimenti in the sitter’s right hand (fig.6). The thumb and fingers were originally drawn in different positions. The infrared reflectogram of the head (fig.10) does not reveal any compositional changes.

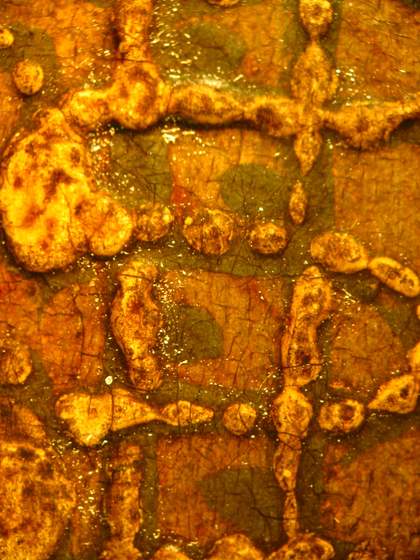

Fig.7

Cross-section taken from the apparently green carpet, 19 mm from the left and 347 mm from the bottom, photographed at x250 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: off-white ground, average thickness 70 microns; oil layer to seal the ground; opaque red paint of carpet, average thickness 20 microns, composed of vermilion, black, red lake and yellow; dark blue paint of patterning, average thickness 15 microns, composed of black, lead white, red lake and probably indigo; varnish and dirt

Fig.8

Cross-section taken from the curtain fringing at the left edge, 1020 mm from the bottom and 19 mm from the left; photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: off-white ground, average thickness 140 microns, composed of marine chalk, lead white, red lead, umber, Cologne earth and bone black; probably a layer of pure oil to seal the chalk rich ground; two shades of opaque reddish brown paint of curtain worked wet-in-wet, average thickness of each stroke 11 microns, composed of vermilion with red lake, black, yellow ochre, lead white, brown earth; dark mustard yellow paint, average thickness 40 microns; varnish layer; pale opaque orange paint (a mordant for the subsequent application of gilding), average thickness 60 microns, composed of chalk, sienna, lead white and black; discontinuous gilding, varnish and dirt

Fig.9

The same cross-section as in fig.8, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.10

Detail of the head and background curtain

Fig.11

Photomicrograph of the sitter’s left eye at x0.8 magnification. The blue pigment in the white of the eye is probably azurite

Fig.12

Photomicrograph of the sitter’s right eye at x0.8 magnification

Fig.13

Photomicrograph of the sitter’s eyebrow at x0.8 magnification

Fig.14

Photomicrograph of a blue vein in the sitter’s hand at x1.6 magnification

Fig.15

Photomicrograph of the earring hoop at x0.8 magnification

Fig.16

Photomicrograph of gilded impasto in the dress at x0.8 magnification

Fig.17

Photomicrograph of gilded impasto in the fringing on the dress, with red lake glaze over opaque red at x0.8 magnification

Fig.18

Photomicrograph of the lace at x0.8 magnification

Fig.19

Photomicrograph of brocade at x0.8 magnification

Fig.20

Photomicrograph of the fabric of the left sleeve at x0.8 magnification

The painting was executed using two techniques: wet-in-wet for the face, hair and the establishing of the folds of the curtain and costume (figs.7–9 and 11); and sequential, layered applications elsewhere, for most of the decorative details such as the fringing and the patterning on the dress done in thick impasto (figs.12–20). Most of the crimson glazes on the curtain have faded with time. The absence of fluorescence in ultraviolet light for these glazes suggests that the paint is bound in oil and that the pigment is a distinct red lake from the more durable madder. It is not clear whether the dress was originally a brighter colour. Analysis of the pigments showed only lead white, black, cologne earth, yellow-brown ochre and chalk, all stable to light, but complete loss of colour in a yellow or red lake would be difficult to observe today. The blue brocade of the dress is based on the pigment azurite, again mixed with chalk, which occurs in nearly all the colours.2

The natural resin varnish comprises several layers (figs.4 and 9) of which none need be original, and it is very yellowed and degraded. In addition to flattening forms, its strong colour conceals, for example the blue patterning in the carpet, which now appears green.

March 2020