Fig.1

British School 17th or 18th century

Portrait of George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury 1600–1799

Tate

T03032

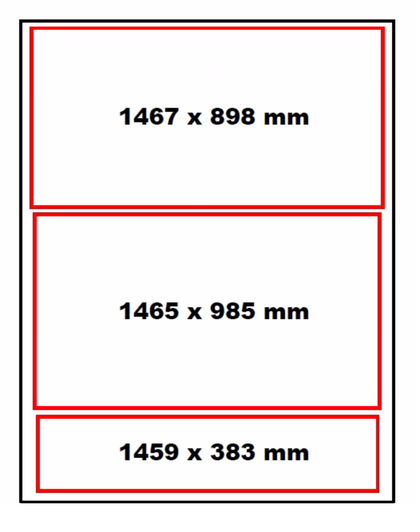

Fig.2

Schematic diagram of the three pieces of canvas making up the support

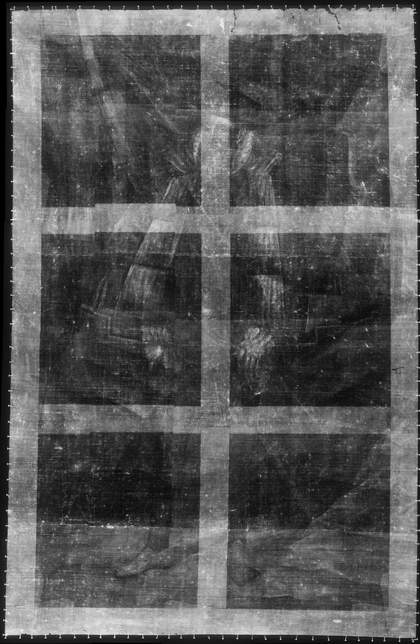

Fig.3

X-radiograph of Portrait of George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury 1600–1799

Fig.4

Infrared photograph of the inscription at the left edge

Fig.5

Detail in infrared of the inscription

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 2264 x 1465 mm (fig.1). The canvas support is composed of three pieces of plain woven, linen canvas, joined together by seams, as shown diagrammatically (fig.2). The three pieces of canvas, though all fine in texture, have different weave counts: the top piece has 16 vertical x 17 horizontal threads per square centimetre; the middle piece has 17 x 17; and the bottom piece has 14 x 18. Although the tacking edges have been removed, there is evidence of cusping along the top, bottom and left edges, but none at the right hand side (fig.3).1 Infrared reflectography reveals that the lettering of the inscription continues at the left edge (figs.4–5). Where the inscription now reads ‘ER: OF SHREWSBWRY’ it used to read ‘RLE: OF SHREWSBWRY’, suggesting the missing letters ‘EA’ of ‘earle’. Estimating from the size of the lettering, this would mean the painting has lost about 5cm on this side. We do not know how much might have been lost from the right side, but given that the figure would need to be fairly centrally placed within the rectangle, probably not very much. The painting has been lined with glue composition and canvas and is attached to a stretcher from a similar date, probably the early twentieth century.

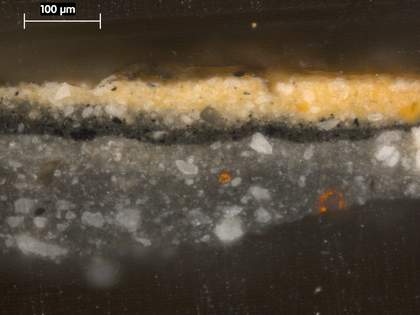

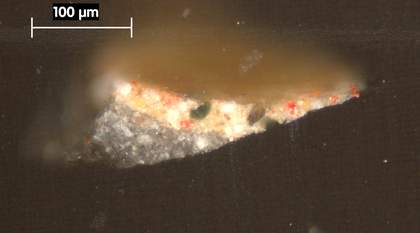

Fig.6

Cross-section through yellow decoration on a shadowed area of the green curtain at the left edge, 121 mm from the top edge, photographed at x250 magnification. From the bottom of sample upwards: dark grey ground, average thickness 100 microns; lighter grey ground, average thickness 50 microns; dark grey background paint, average thickness 20 microns; lighter grey scumble; yellow highlight; trace of green glaze

The ground is thick (average 150 microns) and dark opaque grey in colour, which was mixed from bone black, lead white, sienna and other earth pigments, ground glass, pipeclay and oil. Red particles seen in cross-section are probably red lead, related to degradation of the ground in the form of lead-soap aggregates, which have produced a granular texture throughout the composition. This dark grey is covered over with a thinner coat (average 35 microns) of slightly lighter opaque grey. The similarity of composition of both combined with the smudgy interface seen in some of the cross-sections, suggest that this should be classed as a double ground rather than a ground and a priming (fig.6).

Fig.7

Microphotograph of the nostril at x8 magnification

Fig.8

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the sitter’s right eye

No underdrawing is visible, except during examination with low magnification of the nose and ear, which reveals delineation of the features in red paint followed by thicker black painted definition (figs.7–8). No evidence of pouncing or other direct copying techniques were found.

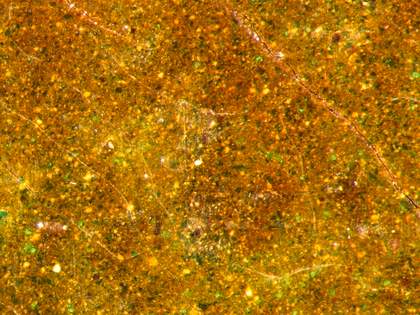

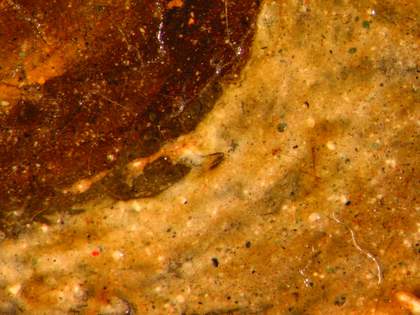

Fig.9

Photomicrograph of the green curtain at x2 magnification

The artist made no attempt to use the colour of the ground in the final composition. Even when painting the grey background, grey paint was applied over the grey ground, as in fig.6. The artist’s palette consists of lead white, a fine bone black, yellow ochre, verdigris, indigo, vermilion, sienna and cologne earth.2 In the highlights of the curtain the olive green dead colouring is a mixture of strongly coloured verdigris, indigo, fine yellow ochre and lead white.3 This appears to have been worked wet-in-wet and was glazed over with verdigris, now discoloured brown (this layer showed no fluorescence in ultraviolet light) (fig.9). It is interesting to note that elemental analysis showed zinc to be present alongside copper in the green curtain, indicating that verdigris made from brass sheeting rather than copper metal may have been utilised.

Fig.10

Cross-section through the face, photographed at x10 magnification, showing green pigment mixed into the flesh tone

Fig.11

Photomicrograph of the eye at x1.6 magnification, showing green pigment mixed into the white

The flesh paints were also found to contain green pigment; this was not positively identified in sampling but is probably green earth (fig.10). The same green is present in the mixture for the white of the eye (fig.11). The absence of lead-tin yellow in any of the decorative highlights may also be significant when considering the date of this painting. Lead-tin yellow is said to have fallen out of use at the end of the seventeenth century.

Chalk was found consistently in all of the paint samples and was probably used as an extender to give bulk to the paint. Likewise, pipeclay and glass were found as additives in many of the paint samples. Glass may have been added to the paint by the artist to aid drying but it is likely that these also acted as bulking agents. Significant amounts of chalk and pipeclay were found in the analysis of the impasto of the decoration for the yellow costume.

Lead soap aggregates are obviously present, as protrusions through the paint surface in almost every paint passage; in the costume (black and grey/white), background and curtain as well as the flesh paint. This suggests that the aggregates are being formed in the ground layer, which was confirmed by their presence in several cross-sections. They confer a transparent appearance on this layer. Despite their widespread occurrence the aggregates are relatively small in scale and not especially disruptive to the overall appearance of the painting. They may contribute to the rather low contrast between the sitter’s black cape and the dark curtain behind him.

March 2020