Fig.1

British School 17th Century

Portrait of Anne Wortley, later Lady Morton c.1620

Tate

T03033

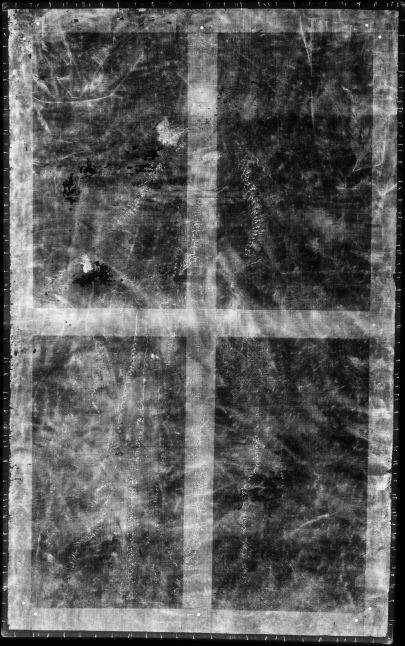

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Portrait of Anne Wortley, later Lady Morton c.1620

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 2063 x 1076 mm (fig.1). The support is a single piece of plain woven linen canvas, fairly tightly woven with 19 vertical and 16 horizontal threads per square centimetre. There is cusping on both upright edges but at the top and bottom it is only faintly indicated, suggesting that between 2 to 4 cm of the painted image may have been cut off at these edges (fig.2).1 The recent conservation history of the painting records that a double glue lining was removed in 1958 and was replaced with the present wax-resin lining. The pine stretcher is adjustable and has a vertical and a horizontal crossbar. It probably dates from the time of the double glue lining.

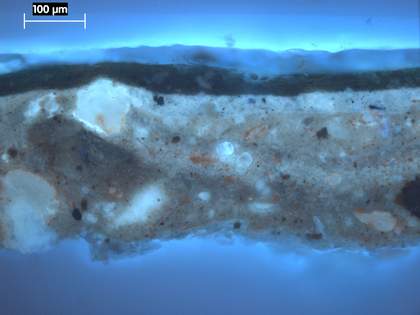

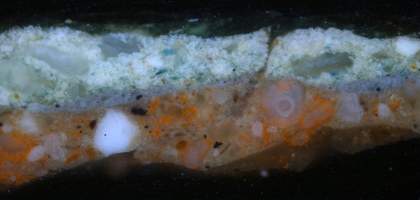

Fig.3

Cross-section through a dark green shadow of curtain, right edge, 415 mm from the top right corner, photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: traces of the size layer applied to the canvas; two coats of salmon pink ground with three lead soap aggregates in the lower layer. Two can be seen at the lower left edge of the sample, the third is pushing up through the upper layer; thin opaque grey priming; opaque dark green underpaint of curtain; translucent green glaze, average thickness 10 microns; varnish

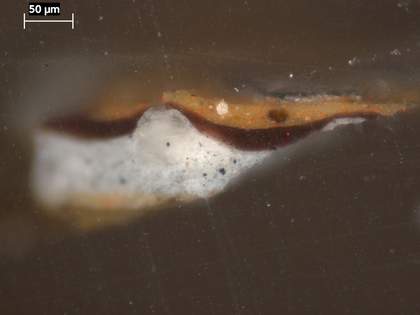

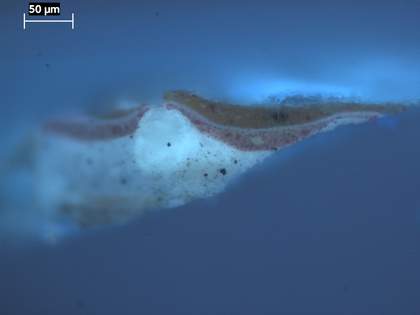

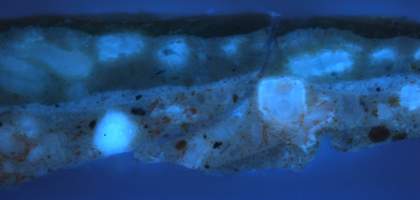

Fig.4

The same cross-section as in fig.3, photographed at x200 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.5

Detail of the curtain in raking light from the right, showing the lead soap aggregates as tiny lumps in the paint

There is a double ground made up of two layers of opaque, salmon-pink paint, composed of lead white, red lead, chalk and a range of red and yellowish-brown ochres (figs.3–4). The canvas had first been prepared with size. The ground has developed lead soap aggregates, that is: tiny rounded aggregates about the scale of granulated sugar, which migrate through the layers overlying them. They are present throughout the painting and are formed by chemical reactions between lead-containing pigments, and the oil binder (fig.5).2

Fig.6

Cross-section through orange painted embroidery in the skirt, 145 mm from the right edge, 480 mm from the bottom edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: size layer; thin sliver of salmon pink ground; grey priming with a lead soap aggregate on the right, pushing up into the next layer; red glaze paint; in ultraviolet light (fig.7) there appears to be an isolating varnish at this point; orange paint of embroidery

Fig.7

The same cross-section as in fig.6, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.8

Infrared reflectogram of Portrait of Anne Wortley, later Lady Morton c.1620

When the salmon-pink ground-layers were dry, a thin, opaque priming of pale, bluish grey was applied. This is composed of lead white, chalk, black, cologne earth and glassy particles. Cross-sections show lead soap aggregates in this layer too (figs.6–7).

No underdrawing is visible with any form of examination (fig.8).

Fig.9

Detail of the head

Paint mixtures for the flesh tones were blended softly wet-in-wet (fig.9). Mixtures contain lead white tinted with vermilion, red lake, azurite and black. The softy outlined shadows defining the features are warm and brownish; the half-shadows around the eyes and mouth are bluish, the tone made by mixing azurite into the basic flesh tone.3 Large flecks of bright red (vermilion) are visible in the flesh tone at the deepest folds in the sitter’s right hand, and the same red was mixed into the flesh tone to create pink shadows around the nails.

Fig.10

Detail of the skirt and left hand

Fig.11

Detail of the lace handkerchief

Fig.12

Detail of the pearls

For the dress the artist mixed three tones of the plum colour on his palette – red lake with black for the middle and darkest tones, red lake with white lead and a bit of black for the highlights. Working quickly, he or she applied these three tones directly to the grey priming, blending them roughly into one another to create the folds and the sense of a shiny surface. The grey priming was deliberately left visible in many places. This brushwork is quite different from the soft blending of the face and probably indicates that the painting is the product of a large studio with many different hands working on one portrait. When all this work was dry, the embroidery was put on with opaque yellow and orange paint, applied freehand rather than through a stencil (figs.10–12). The yellow is lead-tin yellow but the orange is a mixture of lead white, vermilion and a range of yellowish earth and lake pigments.

Fig.13

Cross-section through a highlight of green curtain, 570 mm from top right corner, photographed at x250 magnification. From the bottom of the sample upwards: double salmon pink ground; grey priming; pale green underpaint of curtain, 40–100 microns thick; translucent green glaze, 15–30 microns thick; varnish

Fig.14

The same cross-section as in fig.13, photographed at x250 magnification in ultraviolet light

The curtains were underpainted in three opaque green tones to establish the folds. The opaque greens are mixed from verdigris, lead white, cologne earth and black. These areas were glazed when dry with bright translucent green verdigris, applied evenly. The glaze is thick; the binding medium may be a thickened oil but appears not to contain resin, as it does not fluorescence in ultraviolet light (figs.13–14). For the straw matting, strokes of opaque lead-tin yellow were applied directly to the grey priming, which was left visible around each stroke of paint.

The varnish is a modern synthetic resin.

March 2020