Fig.1

John Hayls

Portrait of a Lady and a Boy, with Pan 1655–9

Tate

T06993

Fig.2

Detail of the two putti in Portrait of a Lady and a Boy, with Pan 1655–9

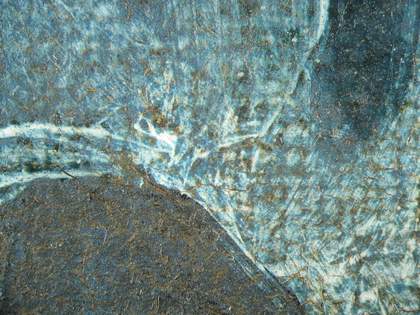

Fig.3

Detail of the sky and trees in Portrait of a Lady and a Boy, with Pan 1655–9

Fig.4

Detail of the righthand putto’s wing in Portrait of a Lady and a Boy, with Pan 1655–9

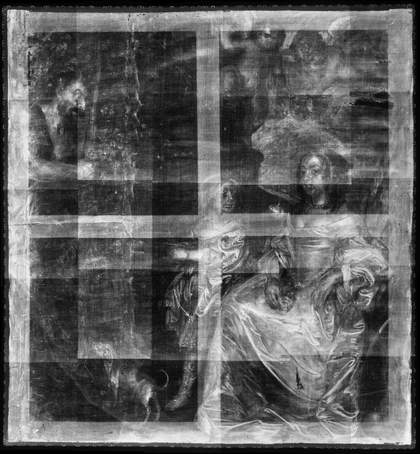

Fig.5

X-radiograph of Portrait of a Lady and a Boy, with Pan 1655–9

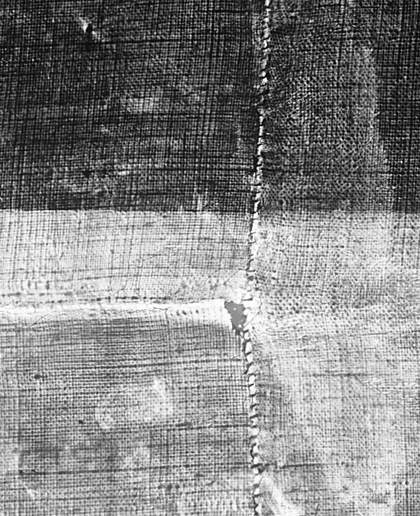

Fig.6

Detail of the X-radiograph of Portrait of a Lady and a Boy, with Pan 1655–9, showing stitched seams

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 1765 x 1645 mm (figs.1–4). The support is made up from three joined pieces of linen canvas – a large piece with an additional broad vertical strip down its left side, formed from two rectangles of canvas one above the other; these small pieces are approximately 51 cm wide. The joins were made by stitching the canvases together, the stitches clearly visible in the X-radiograph (figs.5–6). The weave count for all the canvas pieces is approximately 17 vertical by 17 horizontal threads per square centimetre. The original tacking edges are no longer extant. Cusping is present on the two vertical edges of the painting but is absent at the top and bottom, suggesting that those edges have been trimmed in the past.1 Before the painting was acquired by Tate, it had been lined with glue-paste adhesive onto a backing canvas. It was fitted with a new stretcher after acquisition to replace an older, much damaged strainer with narrow bars and cross-braces at the inner corners.

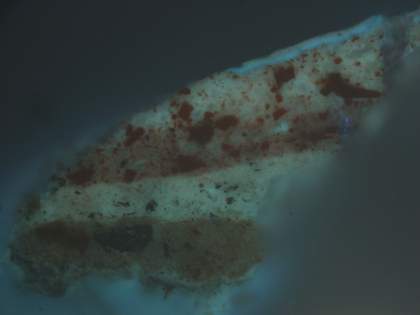

Fig.7

Cross-section through brown foliage at the right edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom upwards: red ground; warm grey priming; opaque brown paint

The ground and priming are identical on all three pieces of canvas – opaque tan coloured ground, overlaid by an opaque, warm grey priming (fig.7). Although rarely left visible in the final painting, the grey priming is just discernible in parts of the boy’s red robe and at minor points elsewhere.

Fig.8

Infrared reflectogram of Portrait of a Lady and a Boy, with Pan 1655–9. It revealed the existence of two putti in the upper right corner and a musical instrument (a theorbo) in the lower right corner

Fig.9

Cross-section through the mustard coloured foreground at the lower left corner, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom upwards: red ground; warm grey priming; thin yellowish brown opaque underpaint; opaque mustard yellow paint

No underdrawing is apparent in normal viewing conditions nor with infrared reflectography (fig.8). Fig.9, a cross-section taken from the mustard coloured foreground at the lower left corner, suggests that the general composition was sketched in with thin yellowish-brown paint, which was left to dry before the final painting commenced.

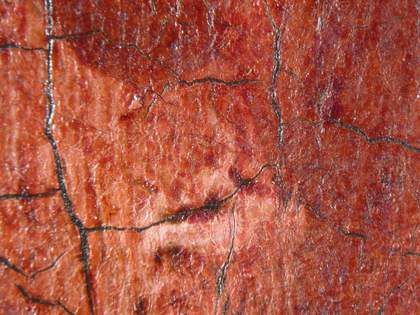

Fig.10

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the boy’s red robe

Fig.11

Cross-section through the boy’s red tunic near the site of fig. 9, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom upwards: opaque tan coloured ground; opaque grey priming; red paint of tunic (two tones of red worked wet-in-wet); two coats of varnish

Fig.12

The same cross-section as in fig. 10, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.13

Photomicrograph x8 magnification of the lady’s blue dress

Fig.14

Photomicrograph x10 magnification of a pearl in the lady’s necklace

Fig.15

Photomicrograph at x12 magnification of the highlight on the pearl in fig.14

The composition was built up using a traditional technique of the type evident in the work of foreign-born painters such as Peter Lely (1616–1680) and Gilbert Soest (c.1605–1681). The majority of the paint layers are opaque and there is relatively little impasto. The paint is well bound in oil and was applied with stiff brushes that describe the contours of the figures and drapery in a bold and lively fashion. Brightly coloured areas such as the boy’s red robe and the lady’s blue dress were painted in opaque undermodelling finished with translucent and semi-translucent glazes (figs.10–13). The faces were begun with thin pink paint, barely covering the canvas weave, and then worked up with additional thin and blended brushstrokes, finishing with slightly impasted highlights. Details such as the lady’s pearls were painted wet-in-wet with inspired brushwork (figs.14–15).

In general, the paint used by Hayls in this picture is very pure – there is very limited use of inert extenders or fillers and the pigments observed are of a high quality with generally large particle size and rich colour. The use of costly pigments such as natural ultramarine is also notable. As was usual in this period, the colours were produced from complex mixtures of pigments, as follows: the blue sky contains smalt, ultramarine, lead white, chalk and charcoal black; green foliage contains azurite with ultramarine plus lead-tin yellow, yellow lake, yellow and brown earth colours, lead white, Cologne earth, charcoal black and a little verdigris; the boy’s blue robe contains azurite, lead white with smaller amounts of iron earth pigments and smalt; the boy’s red skirt contains vermilion and lead white and is glazed with rose madder lake on an aluminium base mixed with gypsum and bone black; the yellow embroidery on the boy’s skirt contains lead white, lead-tin yellow, pipeclay and an aluminium-based yellow lake.2

Fig.16

The painting on arrival at Tate, before conservation treatment

Fig.17

The painting during varnish removal (a block of varnish remains at the left side) and removal of part of the overpainted sky, revealing the faces of the putti

When the painting was acquired by Tate, it had a dense blue sky with no putti visible and no musical instrument (a theorbo) in the right corner (fig.16). The infrared reflectogram (fig.8) revealed the putti and the theorbo. Chemical analysis of the blue sky paint before varnish removal showed the pigment phthalocyanine blue, which was not available before 1935. This and all the other modern repainted areas were removed during varnish removal (fig.17) to reveal the original composition.

July 2021