Fig.1

Marcus Gheeraerts II 1561 or 2‒1636

Portrait of a Man in Classical Dress, possibly Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke

c.1610

Oil paint on panel

556 x 446 mm

T03466

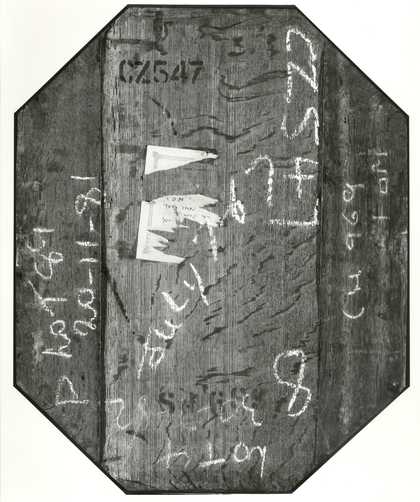

Fig.2

X-radiograph of the whole painting

This painting is in oil paint on an oak panel measuring 556 x 446 mm (fig.1). The panel is made up of three vertical boards, butt-joined with glue and cut on a diagonal at each corner to form an octagon (fig.2). The central board contains the head and measures 252 mm in width; it is flanked on the left by a board measuring 95 mm wide and on the right by one 97 mm wide.

Fig.3

The back of the painting, photographed in black-and-white

The back of the central board displays horizontal saw-marks, whereas the two outer are planed more smoothly (fig.3). Dendrochronology showed that the central board originated in the eastern Baltic region, and indicated an earliest possible felling date of 1597, giving a conjectural usage date of 1597 to 1629.1 The board’s width is close to the typical for the eastern Baltic, suggesting it has not been significantly thinned. No results were possible for the narrower outer boards.

The white ground is thick and is composed of chalk in animal glue (fig.4). Its surface is smooth, with faint vertical and diagonal striations made by nicks in the blade used to scrape it down. There is oil-based priming all over the white ground. It is semi-translucent, brownish grey oil paint and it was applied streakily in broad, largely horizontal brushstrokes, which are clearly visible in the x-radiograph (fig.2). Streaky primings like this are found commonly in the work of painters associated with the city of Antwerp, as we know Gheeraerts would have been via his father, Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder (fl. c.1520/1–1586), who trained there.

Fig.4

Cross-section through the blue background near the sitter’s right shoulder, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: white chalk ground; brownish grey priming; opaque pale grey underpaint; red paint of the bow on the sitter’s shoulder; two coats of blue azurite for the background

Filling up the vertical and diagonal striations in the white ground, the priming appears as the dark streaks beneath the flesh-tones in the neck in the infrared photograph (fig.5). It has another function in helping create the pearly appearance of the skin via an optical phenomenon known as the ‘turbid medium effect’. The explanation, practically speaking, is that if you pass a thin, light coloured layer of paint over a dark area, this dark area will cause the overlying colour to appear cooler, bluer and slightly pearly in tone. It has to do with the scattering of the different wavelengths of light as they pass through a turbid medium, which in this instance is the thin, light toned flesh paint.2

Fig.5

Infrared reflectograph of the whole painting

Dark linear underdrawing is visible with infrared in the hair but if it is present in the face it is no longer apparent (figs.6–9).

The first step in painting appears to have been the application of a bright, opaque, pale bluish grey underpaint to the area designated for the blue background, leaving a reserve for the head and shoulders but not the bunched cape on the sitter’s right shoulder (fig.4). The x-radiograph shows that this grey underpaint extends to the sides of the panel at points roughly level with the sitter’s cheekbones, suggesting perhaps that the full oval border had not yet been planned. The area now covered by the dark oval surround appears to have been laid in with opaque tawny yellow paint (fig.10).

Fig.10

Cross-section through the black oval surround, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: white chalk ground; brownish grey priming; opaque pale grey underpaint; opaque dark yellow underpaint; black paint

With the exception of the face, which was done largely wet-in-wet on the streaky priming, the visible paint layers were generally applied in sequential layers. This was standard practice for Gheeraerts when working on panel, though not when using canvas. The opaque vermilion paint of the cape was glazed with crimson lake, which has faded somewhat with time (fig.11).

Fig.11

Detail of the bow on the sitter’s red cape

Fig.12

Detail of the hair and the background

The azurite background was applied thickly and has undergone noticeable darkening from its original bright blue. It appears to have been applied in two layers, each applied wet-in-wet: the first is medium rich and was put in before the hair, which extends over it; the second application is thicker and contains more brilliant, better quality azurite. It stops short of the hair (fig.12).

The painting was cleaned and restored at Tate in 1983.

May 2004