Fig.1

British School 17th century

Portrait of a Man c.1670

Oil paint on canvas

756 x 630 mm

N03546

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 756 x 630 mm (fig.1). The canvas is plain woven linen with a thread count of approximately 12 by 12 threads per square centimetre (fig.2). The canvas is fine and looks to be of good quality with no slubs and relatively even threads. Cusping is present on all four sides and seems slightly more pronounced at the top and bottom, perhaps indicating that the weft runs in the vertical direction.1 The unprimed tacking margins are present on all four sides.

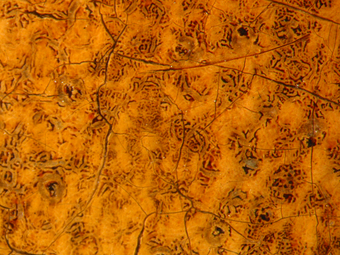

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Portrait of a Man

The ground is warm orange colour, applied thinly. It is rich in calcium carbonate (chalk) with a little lead white, black, red lead and earth colours.2 The priming, which covers the entire ground layer, is opaque pale pink colour (fig.3). Under low magnification granular lead white particles are visible in a pink matrix, along with three types of red pigment (red lead, red lake and red ochre), a black in lower concentrations and the occasional yellow and brown earth particle. Analysis with higher magnification revealed that the priming also contains chalk, probably added as an extender, and glassy particles, possibly added as a drier. The priming is of medium thickness (50 microns). Its reddish tone enriches the colour of the warm brown background and it is visible in many areas due to old abrasion of the overlying paint.

Fig.3

Cross-section from the grey stone oval, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: chalk-rich ground; opaque pink priming; opaque, greyish brown paint

The portrait is finely painted with visible brushwork but little impasto. Some barely noticeable strokes in the face become very pronounced in infra-red reflectography (figs.4 and 5). These seem to relate to underpainting rather than the final painting but cannot be said to represent underdrawing. The artist began the work by positioning the sitter’s head and collar.

Fig.4

Infra-red reflectogram of Portrait of a Man

Fig.5

Infra-red detail of face

The face was first laid down with a thin, warm reddish-brown paint, which is visible in the worn areas in the sitter’s pupils (fig.6), and then built up with more bodied paint, applied mostly wet-in-wet. Notable exceptions to this are the whites of the sitter’s eyes, which were applied in thick paint and allowed to dry before the addition of the darks of the pupil, the iris and the final, delineating red lines of the socket. Also of interest is the way the left nostril cavity was finished with three bold, opaque red strokes over the dark red glaze (fig.7).

Fig.6

Microphotograph of eye, showing reddish brown underpainting beneath the final painting of the iris and pupil

Fig.7

Microphotograph of sitter’s left nostril, showing final, bold strokes of red paint

The collar was blocked in with a mid-grey underpaint which has been left uncovered in areas to stand as shadow. The red drapery and brown background were then painted up to the grey reserve. In the robe the artist laid in the drapery with a mid-tone of thin, brushy, translucent red paint, and then added the more bodied yellowish pink highlights and dark shadows. The paint for the darkest red shadows of the drapery was mixed from red lake, red and brown earth pigments, lead white and bone black, the highlights from lead white, red lake, lead tin yellow, red and yellow earth pigments and Cologne earth. Flesh tones were made with lead white mixed with vermilion, chalk, earth pigments and bone black.

The feigned oval stone frame was painted on after the portrait was finished and can be seen to lie over drapery and the brown background colour. However, this frame motif was intended to be present from the outset, since the composition of the portrait has not been painted up to the edges of the canvas, rather it extends just a few centimetres under the inner edge of the feigned stone frame.

Fig.8

Micrograph showing hexagonally-shaped microcissing that has broken up the crimson glaze

Fig.9

Small paint losses caused by lead soap aggregates reveal the pale pink priming

The yellowish pink highlights of the red drapery are broken up with microscopic craters containing the residues of old varnish; this is a type of microcissing (fig.8). Drying cracks on a larger scale were also found in the dark brown paint of the feigned stone frame where it overlay the yellowish pink paint. Lead soap aggregates, or the tiny paint losses caused by them, occur across much of the paint surface (fig.9).3 Examination of cross-sections indicates that these aggregates originated in the ground or priming.

In 1971 the painting was cleaned and restored at Tate; the final varnish applied during the treatment is one of the earliest uses in Britain of the synthetic resin Paraloid B72. The existing lining of glue-composition and canvas was removed, after which the original canvas was stuck down with wax-resin adhesive to a rigid support to serve as a stable, lightweight support for old tears in the canvas.

July 2004