Fig.1

?British School, 16th Century

Portrait of a Gentleman, probably of the West Family

1545–60

Oil paint on panel

1333 x 784 mm

N04252

This painting is in oil paint on an oak panel measuring 1333 x 784 mm (fig.1). The panel is composed of three boards, placed vertically and glued together at butt joins (fig.2). The X-radiograph shows that the boards were kept in position until the glue dried with wooden dowels inserted into the inner edges (fig.3).

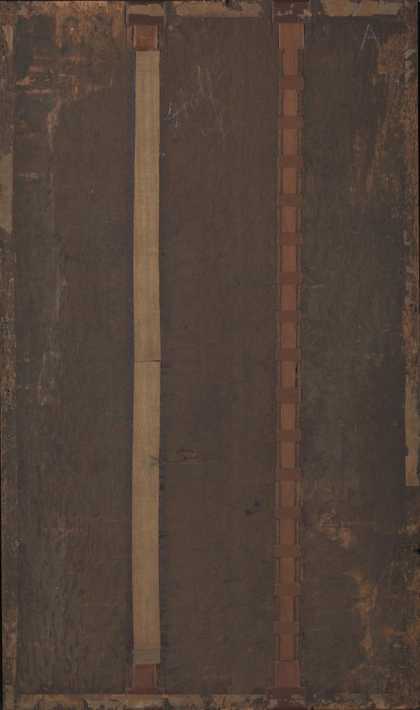

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Portrait of a Gentleman, probably of the West Family

Fig.3

Detail of the X-radiograph, showing the horizontal dowel in the join between two boards, near the top right corner

Dendrochronological examination revealed that the three boards are from the same tree that grew in the Baltic region.1 The youngest heartwood ring was formed in 1510 or 1511 and the probable earliest felling date is 1519, although from 1523 to 1529 is more plausible. The wood may have been used for painting between 1519 and 1546. On the back of the panel is an incised mark, thought to be a cargo mark made for the transit of the wood across the Baltic Sea to England (figs.4–5).

Fig.4

The back of the panel, photographed in black-and-white. It shows later reinforcement of the joins with fabric, inset wooden strips and wooden buttons. The incised mark is near the lower left corner.

Fig.5

Detail of the incised mark on the back of the panel

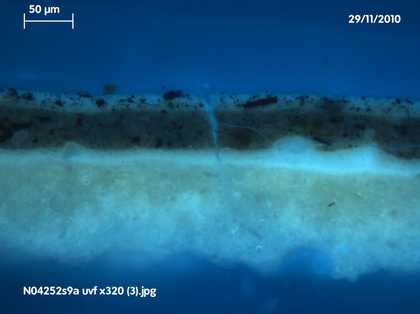

The ground is off-white and is made of marine chalk bound in glue and possibly casein, although the latter material may have been introduced as a consolidant later in the painting’s history.2 Identification of nano-fossils in the chalk revealed that it dates from the earliest Santonian-late Coniacian period.3 Deposits of chalk from this period are found around London and also in the North Downs, the Chilterns and Hertfordshire. They occur also in France, to the south and west of Calais. The ground is covered with white, oil bound priming (figs.6–7).

Fig.6

Cross-section through the background at the top edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: off-white ground; white priming; brown underpaint of background; grey paint of background; varnish

Fig.7

Cross-section through the background at the top edge, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: off-white ground; white priming; brown underpaint of background; grey paint of background; varnish

When viewed with low magnification and with infrared reflectography, the face and hands display bold, linear, freehand underdrawing (figs.8–10).

No underdrawing is detectable with infrared reflectography elsewhere in the painting, although a cross-section through one of the painted red slashes on the doublet revealed what may be a drawing line (figs.11–12).

Fig.11

Cross-section through a red slash on the left side of the doublet, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: white priming (the ground is missing from this sample); traces of black pigment, which may constitute underdrawing; thick yellow mordant for the overlying metal leaf; silver leaf; red lake glaze

Fig.12

Cross-section through the proper left slash in the doublet, photographed at x225 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: white priming (the ground is missing from this sample); traces of black pigment, which may constitute underdrawing; thick yellow mordant for the overlying metal leaf; silver leaf; red lake glaze. The fluorescence in the glaze paint may mean that its binding medium is oleo-resinous

The artist appears to have begun the painting with a thick coat of yellowish-brown underpaint in the area of the background, leaving reserve spaces for the figure (figs.8–9 and fig.13).

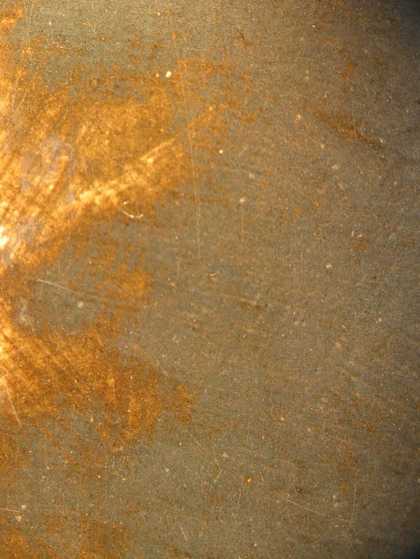

Fig.13

Detail of worn grey paint in the background, showing the yellowish-brown underpaint

The braid on the costume is also underpainted similarly; the main pigment in the brown underpaint is Cologne earth (fig.14).4 It is not clear what sort of preparatory lay-in was made for the black costume. The breeches were painted with mixtures of bone black, lead white, red lake and chalk, applied wet-in-wet.

Fig.14

Cross-section through yellow braid on the costume, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: off-white ground; white priming; yellowish-brown underpaint; thick yellow paint of the braid, composed of lead-tin yellow type I, vermilion and lead white

A different type of black (vine black perhaps) was used for the cape, and the paint was applied in small dabs to simulate the texture of the wool or fur (fig.15). The decorative details of the embroidered shirt were applied on top of the white paint of the shirt when it had dried (fig.16).

Fig.15

Detail of the sitter’s right shoulder, showing the black paint of the cape applied in dabs

Fig.16

Detail of the embroidery on the shirt

The red glaze paint on the slashes in the doublet are made from a red lake pigment made from the insect dye, cochineal (Dactylopius coccus Costa), struck onto a base of alumina; at this date the dyestuff would have been sourced from the New World.5 The red glaze was applied on top of silver leaf, which was laid onto a thick, yellow mordant (figs.11–12 and fig.17). The yellow braid contains lead-tin yellow (type I) and vermilion.6

Fig.17

Detail at x8 magnification of the red glaze on top of silver leaf. A sample was taken for analysis from the glaze as it abuts the edge of an old grey filling put in to repair a damage.

The most unusual feature in this painting is the technique used to paint the face (figs.18–22). The tones were applied in finely hatched lines. No specialist in European art of the sixteenth century could identify this technique as of the period or associate it with any known artist. It is possible that this is the work of a later hand (perhaps from the nineteenth century) making good a disastrous damage to the original, but without extensive (and undesirable) sampling of the face, this is impossible to prove.

The coat of arms on the ring is difficult to discern but this may be due to the fading of a red lake pigment in the lines that are now pale orange colour (fig.23).

Fig.23

Detail of the coat of arms on the ring

A detailed paper on this painting appears in Tate Papers as Natasha walker, Karen Hearn and Joyce Townsend, 'Tate’s Painting of a Man in Tudor Costume: A Sixteenth-Century Portrait or a Nineteenth-Century Pastiche?', Tate Papers, no.20, Autumn 2013, accessed 29 July 2016.

August 2016