Fig.1

Marcus Gheeraerts II 1561 or 2‒1636

Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee

1594

Oil paint on canvas

2150 x 1330 mm

T03028

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 2150 x 1330 mm (fig.1). The canvas is a single piece of plain, very finely woven linen. To date, it is the earliest painting on canvas in Tate’s collection. Woven linen has a long history of use as a support for painting. It served this purpose in Ancient Egypt, and there are documentary references to its use in Europe during the fourteenth century.1 The earliest surviving examples in Western art, however, are from the late fifteenth century, from which period a few religious paintings have survived, for example The Entombment of Christ by Dieric Bouts in the National Gallery, London. By the mid-sixteenth-century in Venice stretched linen had all but replaced panel for most genres of painting, but elsewhere the change was more gradual; considerations of size, the need for portability and its greater suitability for the ‘painterly’ style probably vied with tradition for many years as the factors in the choice. There are examples of full-length portraits on canvas from various courts in Europe from the 1560s but in this, as in so many other matters artistic, England appears to have lagged behind. Marcus Gheeraerts was among the first artists to popularise canvas for formal English portraits. His full-length, Queen Elizabeth I, The Ditchley Portrait [National Portrait Gallery], is from about 1592 and the Woburn Abbey Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex from around 1596.2

Fig.2

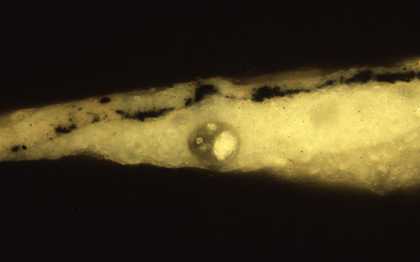

Cross-section through a vein in the sitter’s right leg. From the bottom: white ground; white priming; black pigment for the vein; flesh paint; traces of varnish

The ground is off-white in colour and is composed mainly of chalk with gypsum, lead white, some ochres and lamp black (fig.2).3 It was applied after the canvas had been given a thick coat of animal glue size. The ground is covered by white priming, which is thicker than the ground and is made principally of lead white with small amounts of the other ingredients. Both layers appear to be bound in oil.

Fig.3

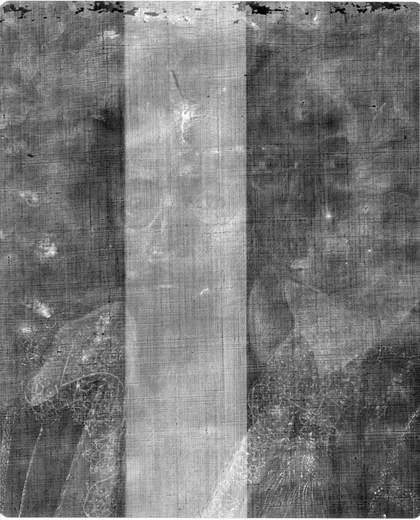

X-radiograph of the sitter’s head, showing the underlying head off-set to the right

Before Gheeraerts drew the outlines of the figure that we see in this painting, he had started another portrait, whose painted head and collar appear in the X-radiograph (fig.3). This head is off-set from centre and no other trace of the figure is visible with any form of technical examination. The absence of a beard makes it unlikely that this was a false start for Captain Lee.

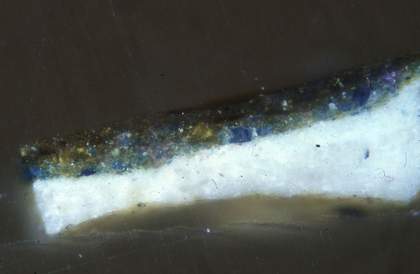

Fig.4

Cross-section through the right side of the sitter’s hair, showing the pink flesh paint of the underlying head. From the bottom: white ground; white priming; pink paint of earlier head; white paint to obliterate the head; brown paint of Captain Lee’s hair

A cross-section sample, taken from the right side of Captain Lee’s hair, shows this underlying pink flesh paint and the coat of off-white paint used locally to obliterate it (fig.4). The artist then appears to have drawn the outline of the present figure fairly simply in black crayon, although it is not easy to detect with either infrared or surface microscopy except in one area: the veins in the legs. This usage relies on the knowledge that a dark line or mark beneath a thin layer of lighter opaque paint will read as a darker, pearly tone of the overlying colour; it is known as the ‘turbid medium effect’.4 Many a sixteenth-century portrait painter utilised it in the flesh tones, including Gheeraerts in his Portrait of Philip, 4th Earl of Pembroke (Tate T03466).5 Here, however, Gheeraerts has not used it in the densely painted face and hands, in which all the tones were mixed up on the palette and applied wet-in-wet; he has kept it only for the striking presence of the veins in the legs. A cross-section through the vein on the front of his left leg (fig.2) shows the black crayon-line beneath the flesh tone, in which colour there is no modulation at this point. Given the tendency of oil paint to become more translucent with time, these lines are probably more visible now than in 1594; nevertheless they would always have been a noticeable and quite intentional feature of this portrait.

Fig.5

Cross-section through foliage, showing wet-in-wet application of the green tones. From the bottom: white priming; shades of green brushed into each other while wet

In most areas of the painting the colours were pre-mixed on the palette and worked into one another wet-in-wet on the prepared canvas support (fig.5). Most colours are opaque. The only discernible preparatory underpainting is in the shield on his shoulder, where opaque paint was glazed with a red lake. The sky was made from mixtures of lead white and smalt, in which pigment there has been some fading. The principal pigment in all the greens is azurite mixed with varying amounts of yellow and red earth colours, lead tin yellow or massicot, Cologne earth, black, green earth and pale smalt or ground glass. For the distant, bluish green hills Gheeraerts mixed the azurite with lead white and smalt. There has been loss of colour in the centre of the woods to the right of his head, an area that now looks yellowish brown. Originally it was probably a dark bluish green, smalt apparently being the component that has faded. The flesh tones contain lead white, chalk, vermilion and small amounts of black, azurite and yellow ochre. His shirt is lead white mixed with bone or ivory black, and the blackwork embroidery was applied on top. His jerkin appears to be lamp black, the blackest of black pigments but a very slow drier in oil. This probably accounts for the presence of ground glass or pale smalt in the mixture to act as a siccative. Ground glass occurs also and for the same reason with the yellow ochre describing the braid on his jerkin. The highlights here are lead tin yellow or massicot. The shield was painted first in an opaque red mixture before being given a thick glaze of red lake with a bit of black mixed in to enrich its tone. The extensive use of wet-in-wet work in this painting on canvas is quite different from Gheeraerts’s technique for panel paintings; there he painted the face wet-in-wet but used a sequential, layered technique for the costumes and backgrounds.6

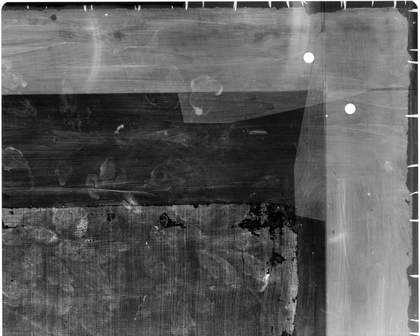

A deep band of paint above an imaginary horizontal line about 3 cm from the top of the sitter’s head is a later addition. When the painting was acquired by Tate in 1980, it was evident on stylistic grounds that all four sides had been extended at some later period. The extensions were not made by sewing pieces of canvas to the outer edges of the original; instead the painting was lined onto a double thickness of canvas and mounted onto a larger stretcher. While the painting was being cleaned at Tate in 1994, these painted margins were examined and analysed microscopically to ascertain their date and to see if they might be replacing original canvas now lost. The presence of Prussian blue in the foliage on the additional canvas above the sitter’s head indicated an earliest possible date of about 1710. Large quantities of bitumenous pigments in all the additional areas except the sky suggested an actual date in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Until the 1930s the painting remained at Ditchley, the home of Captain Lee’s kinsman and patron of Gheeraerts, Sir Henry Lee. It is possible that the enlargement was done in order to incorporate the painting into a decorative scheme containing full-lengths of a later date, in which on average there is more space around the figure than in late Elizabethan portraits. The X-radiograph and subsequent cleaning revealed that by the time of the first lining the edges of the original canvas had suffered much damage. Each edge was punctured at regular intervals by old tack holes around each of which the paint and canvas were worn (fig.6). The painting had probably been left to deteriorate on its original strainer, falling loose as the canvas rotted around each tack; a ready solution, found often enough in old collections, would be to reattach the painting by nailing into the strainer from the front. It was clear from the X-radiograph that the painting could never have been much larger than 2 or 3 cm beyond the tackholes because on each edge apart from the top there is cusping of the canvas weave, which relates to the earliest stretching of the painting (fig.6).7 The absence of cusping along the top edge and the knowledge that this edge cuts through the crown of the earlier head, indicated that more original canvas had been removed here, but there was no evidence to suggest how much. So the decision was made to cut the upright and bottom edges back to their maximum possible original size, using the cusping as a guide, and to leave the top as it was.

Fig.6

X-radiograph of the top right corner of the painting before removal of the extensions. Note the old damage to the edges of the original canvas and the cusping in its right edge

Apart from the losses at the edges and the colour changes noted above, the painting is in exceptionally good condition, particularly for this period in which historic methods of cleaning have in too many examples wrought damage on a sad and serious scale. One reason for this fortunate escape may be the presence in some areas of a very old varnish, which is resistant to the gentle methods of cleaning used today and may have protected delicate areas in the past. There is no way of telling if it might be the original varnish but its presence in samples taken from the real top edge of the painting, where it is overlapped by paint from the extension, indicates an eighteenth century or earlier origin. It extends over most of the dark greens and browns in the lower half of the painting and in some areas on the right. A few, very minor patches of abrasion in the embroidered shirt and in the legs suggest that this tough varnish once covered the whole painting, and we have been lucky that the person who had to rub hard to remove it from the figure and sky stopped when he or she did. This varnish was not removed in the cleaning of 1994 because it would have required the use of solvents considered unsuitable for the painting. There is probably, therefore, more contrast than originally in the tonal relationship between the figure and the landscape.

January 1999