Fig.1

Sir Godfrey Kneller 1646−1723

John Smith the Engraver

1696

Oil paint on canvas

758 x 630 mm

N00273

The painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 758 x 630 mm. The support is a single piece of plain woven linen, which has 14 vertical and 12 horizontal threads per sq cm; there are many slubs, mostly in the horizontal direction. The canvas has regular cusping on all edges (fig.2).1 The original stretcher has not survived and there are no bar-marks to indicate its style. The painting has been lined with glue-paste adhesive, probably in the nineteenth century. The five-bar, pine stretcher looks contemporary with the lining.

Fig.2

X-radiograph of John Smith the Engraver 1696

The ground is pale bluish grey colour. Its surface bears the marks of the tool that was used to apply it: faint, mainly horizontal ridges, approximately 2 or 3 to a millimetre in width, are visible in the background where the paint is thin. As viewed in some of the cross-sections, the ground may have been applied in two coats, the first slightly warmer in tone than the second – but the difference is minimal (fig.3). The pigment content is lead white, chalk (large proportion), bone black, ochres, azurite, and glassy particles.2

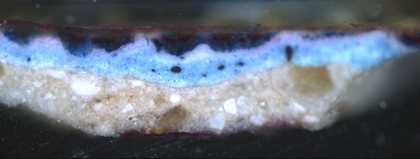

Fig.3

Cross-section through the background, photographed at x 200 magnification. From the bottom up: a thick coat of glue size applied first to the canvas (stained red with Acid Fuchsin); opaque grey ground, possibly applied in two coats, the first slightly warmer in tone that the second; thin, opaque pale brown paint; several coats of varnish and dirt

No preparatory drawing is visible in normal viewing or infra-red. The shadowed outlines on the face and hands are painted reddish brown, which was probably used also for the first outline of the face on the canvas (fig.4).3

Fig.4

Detail of the face

Only one part of the composition has underpainting: the light areas of the turban were laid in with thick, opaque mixtures of indigo and lead white, the different shades worked up wet-in-wet on the canvas. They were glazed when dry with ultramarine (figs 5 and 6). For the rest of the portrait Kneller worked wet-in-wet directly onto the ground with thin, rather lean paint, using the marks of the brush to help describe the form and to vary the translucency of the colour.

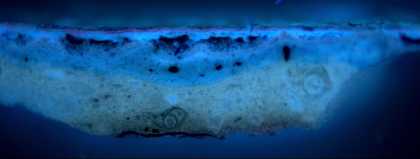

Fig.5

Cross-section through the highlight of the cap, photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom up: a thick coat of glue size applied first to the canvas (stained red with Acid Fuchsin); opaque grey ground; several shades of opaque pale blue paint worked together wet-in-wet on the painting; thin dark blue glaze; residue in the pits of the paint film, stained dark red with Acid Fuchsin; several coats of varnish, dirt and glue from old restorations, with some red staining from the Acid Fuchsin

Fig.6

The same cross-section as fig.3 photographed in ultraviolet light

The pink flesh tones were mixed from lead white, vermilion, red lake, red ochre, black and azurite. Unlike some of Kneller’s ‘Kit-cat’ portraits, where the grey ground appears to have been left unpainted to form the whites of the eyes, Smith’s eyes are painted with very thin opaque yellowish grey paint, now much worn and showing the colour of the ground beneath.4 Grey half shadows in the face were originally glazed or scumbled very thinly with pale reddish flesh tone; again, they are now much worn and showing the ground colour beneath.

Unusually for a seventeenth-century painting, the paint in all areas of the composition is microcissed – that is, has formed microscopic craters in the whites and flesh tones, and darker paint has shrunk into small islands or dots.5 A dark, resinous residue is visible in the hollows of the paint film all over the picture. In cross-section this layer fluoresces opaque grey in UV and is stained red by Acid Fuchsin, indicating a proteinaceous nature (figs.5 and 6).

When this study was undertaken, this residue lay beneath several coats of natural resin that have become dark with age. Since then the painting has been cleaned.

June 2005