Fig.1

Gilbert Soest

Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk c.1670–75

Tate

T00746

Fig.2

Detail of the head of Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk c.1670–75

Fig.3

Detail of Henry Howard’s right hand and sleeve

Fig.4

Close-up of Henry Howard’s right hand

Fig.5

Detail of the ships and sky in Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk c.1670–75

Fig.6

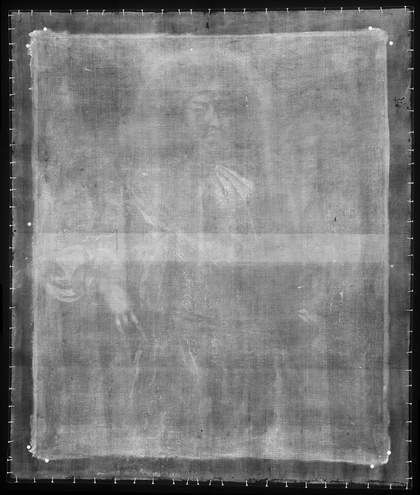

X-radiograph of Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk c.1670–75

This painting is in oil on a canvas measuring 1270 x 1073 mm (figs.1–5). The support is composed of a single piece of fine, plain woven canvas, which is now lined to a secondary canvas with glue-paste adhesive. The stretcher appears contemporary with this lining. The original tacking margins remain and are now in part included in the picture plane at the bottom and upright edges. Linear cracking from an early strainer or stretcher is visible 60 mm from the vertical edges (the current stretcher bars are 80 mm wide). The canvas has a weave count of 18 vertical and 17 horizontal threads per square centimetre. The back of the original canvas appears to have been given a coat of X-ray dense paint while on the earlier stretcher or strainer (fig.6).

Fig.7

Photomicrograph at x5 magnification of unpainted ground at the edge of the painting

(the bluish grey flecks are later retouching)

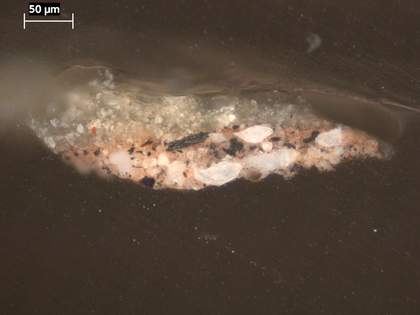

Fig.8

Cross-section from the palest passage of the sky near sitter, 596mm from the bottom and 257mm from the right edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom upwards: pink ground; amorphous grey sky paint composed of lead white, chalk, and smalt which was once blue but is now colourless

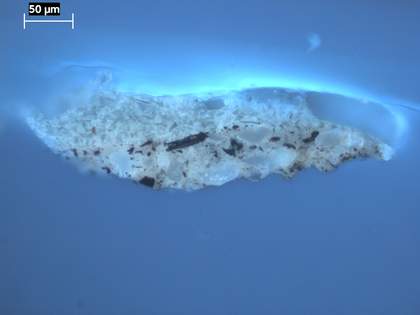

Fig.9

The same cross-section as in fig.8, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light. Note the glassy shards of smalt in the paint layer

Fig.10

Infrared reflectograph of Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk c.1670–75

The ground is opaque dark pink colour and it is composed of coarsely ground black and white particles in a pale pink matrix (figs.7–9); analysis showed lead white, earth colours, bone black and pipeclay as the principal components.1 There is no priming over the ground, and no underdrawing is visible with any means of examination (fig.10).

Fig.11

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the sky, showing brush marks and old abrasion of the paint

Fig.12

Cross-section taken through the blue sky immediately above the sitter’s head, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom upwards: pink ground; discoloured sky, containing lead white, smalt and black; brighter blue sky containing lead white and indigo

Fig.13

The same cross-section as in fig. 11, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.14

Close-up of face, showing dark red touches to accentuate the eyes

Fig.15

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the sitter’s right eye

Fig.16

Photomicrograph at x8 magnification of the sitter’s left eye

Fig.17

Detail of the hand, showing dark red touches to accentuate the fingers

The paint is thinly applied and has been worn from early cleaning. Despite this, the paint texture still retains a brushy appearance from stiff hogshair brushes (fig.11), as seen in the other paintings by Soest. The paint contains numerous brush hairs, indicating a vigorous application. Large areas of the sky and possibly also the grey costume have faded, mainly because they contain large amounts of smalt, which has turned from blue to grey (figs.8–9). This helps explain the curiously livid areas of the sky, which originally would have been bright blue. The bright blue halo around the sitter’s head appears to have been applied after the rest of the sky and it contains the blue pigment indigo rather than smalt (figs.12–13); when first applied it would have matched the original blue of the rest of the sky. There has also been fading of red lake pigments, notably in the pink ribbons of the costume. A notable feature of the technique is the application of dark russet coloured paint to accentuate the eyes and the fingers (figs.14–17). This occurs in other paintings by Soest, though sometimes in a more delicate manner.

July 2021