The painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 2348 x 2838 mm (figs.1–5). The canvas support is composed of two pieces of plain woven linen joined at a vertical seam just to the left of centre (fig.6). The left hand piece is approximately 1355 mm wide, the right hand piece 1483 mm. Both pieces of canvas have a thread count of 14 vertical threads and 12–14 horizontal per square centimetre.

Fig.6

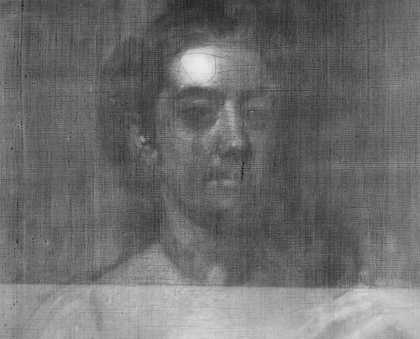

X-radiograph of the youngest child’s head, showing the seam joining the two pieces of canvas

The painted composition continues over onto the tacking edges, which suggests that the painting has been reduced in size; this theory is reinforced by the absence of cusping around the painting’s edges.1 The alignment of the composition suggests that slightly more of the picture has been lost from the left than the right. A vertical line of filled tack holes, 4 cm in from the left edge, indicates either that the painting was once stretched on an even smaller stretcher or, more probably, that at some point the original left edge was so badly damaged that the painting had to be reattached to the stretcher bar with nails through the front. There is no evidence for the size of the original stretcher. The painting has a modern lining and stretcher, the latter of which was fitted after acquisition by Tate in 2005.

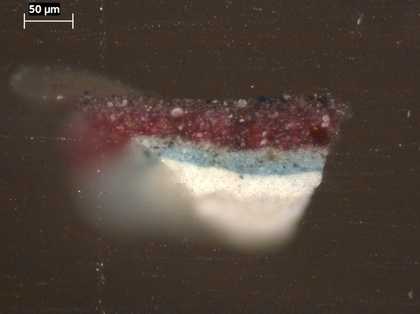

Fig.7

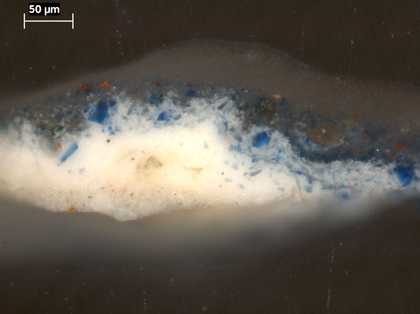

Cross-section through a mid-tone of the blue drapery, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: tan coloured ground; grey priming; opaque pale blue paint, which contains lead white and indigo; dark blue semi-translucent glaze paint containing ultramarine blue, smalt and other pigments; modern retouching; varnish

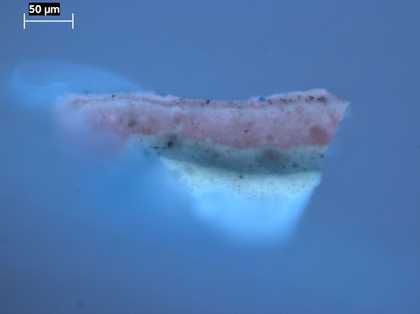

Fig.8

Cross-section through a mid-tone of the blue drapery, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light used with a blue filter. From the bottom: tan coloured ground; grey priming; opaque pale blue paint, which contains lead white and indigo; dark blue semi-translucent glaze paint containing ultramarine blue, smalt and other pigments; modern retouching; varnish

The ground layer is an opaque tan colour composed of earth colours and lead white mixed together in oil. The ground is covered over with an opaque, warm pale grey priming layer (figs.7–8). This was made from lead white, fine black, yellow ochre, raw sienna, green earth and glassy particles, again bound together in oil.2

In common with many British paintings from the first half of the eighteenth century, the surface of the ground is textured with tiny ridges, some two to three to a millimetre’s width. They are regularly horizontal all over and were made by the tool with which the priming was applied (fig.9).3

Fig.9

Detail of the yellow dress at x10 magnification, showing the horizontal striations in the priming

Close inspection indicates that the artist used linear brush drawing in thin brown paint to set down the position of the figures. Infrared reflectography revealed no further evidence of underdrawing, except for what appear to be painted lines in the younger woman’s face, which are not evident in normal viewing (figs.10–13).

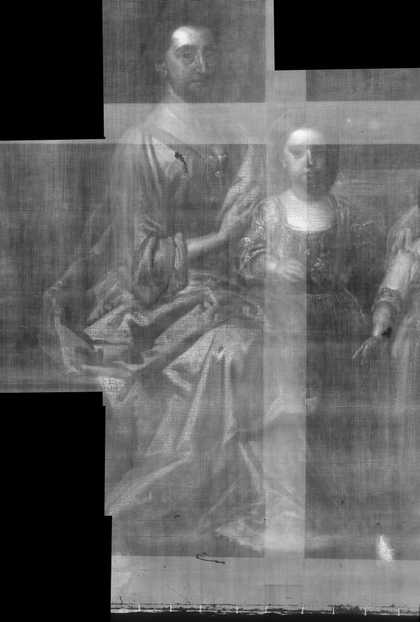

The reflectograms revealed few significant alterations in the composition; changes to the boy’s left shoe and in the dog can be seen with the unaided eye. It did reveal, however, something of the order of painting; the smallest child’s left hand appears to go over the already executed hand of her mother. Likewise, the male sitter’s right-hand little finger extends over the background.

Fig.14

Detail at x10 magnification of the apron of the middle child, showing the priming left visible as a tone in the composition

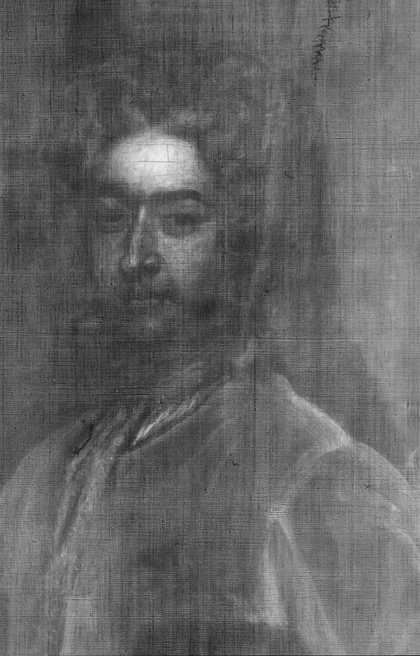

Compared with many of Kneller’s earlier works, the colour of the priming does not play a significant, visible part in the composition. It was left visible as the mid-tone of the apron of the older child in the centre (fig.14) but, as may be discerned in the X-radiograph details, the dense, opaque paint of the composition was applied and blended to give a smooth overall texture, particularly in the sitters’ faces (figs.15–18). This contrasts strongly with the rougher, brushy texture found in Kneller’s earlier work.

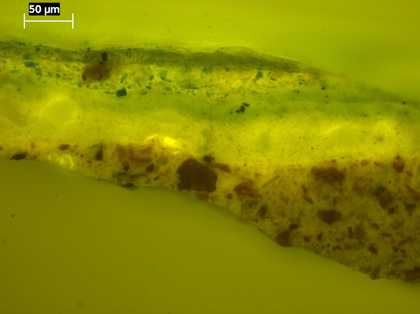

Underpainting exists in some of the costumes: blue and white beneath the deep blue drapery of the older, female sitter (which may account for the wide drying cracks in this area) (fig.19); violet drapery is underpainted in shades of dull pink and blue (figs.20–21).

On the other hand the yellow dress was applied in three, simple shades directly to the ground, wet-in-wet. This is true also of the costumes of the gentleman and the oldest boy. There is substantial glazing in the lilac dress. In this and the blue drapery, complex glazing was modified by superimposed strokes of intensely bright, opaque colour, which occasionally was glazed over again (figs.22–24). There is a copper resinate type of glaze in the green drapery of the middle child; this has taken on a brownish tone. Overall, the palette is bright and more intense in colour than any of the other paintings by Kneller in Tate’s collection.