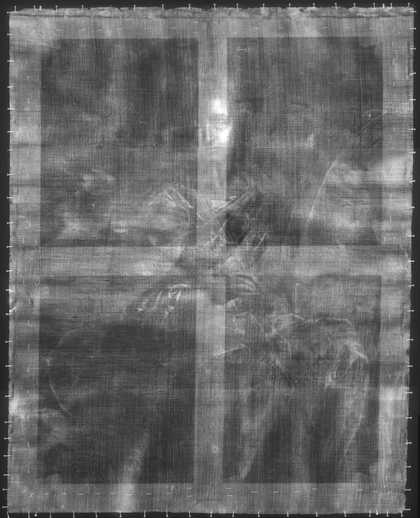

Fig.1

Benedetto Gennari 1633–1715

Elizabeth Panton, later Lady Arundell of Wardour, as Saint Catherine 1689

Oil paint on canvas

1250 x 1021 mm

T06897

This painting is in oil on canvas measuring 1250 x 1021 mm (fig.1). The single piece of plain linen canvas was woven with 13 vertical and 12 horizontal threads per square centimetre. It has a glue-paste lining and is mounted with steel tacks onto an adjustable pine stretcher; the lining and stretcher probably date from the early twentieth century. Bar-marks in the painting indicate that the original stretcher had a narrow horizontal crossbar. All four tacking edges have been reduced in width and are now partially incorporated into the composition. This is most apparent along the top edge where up to 1.2 cm of tacking edge has been flattened to be included in the picture plane. The X-radiograph shows an indented line running across the top of the picture, about 2.5 cm below the top edge; its origin is unclear (fig.2). Obvious cusping is visible in X-radiograph at the left and right edges, but is only just noticeable at the top and almost completely absent at the bottom.1 The canvas contains several very large slubs, one in particular above and to the right of the sitter’s head is obvious through the paint.

Fig.2

X-radiograph of Elizabeth Panton, later Lady Arundell of Wardour, as Saint Catherine 1689

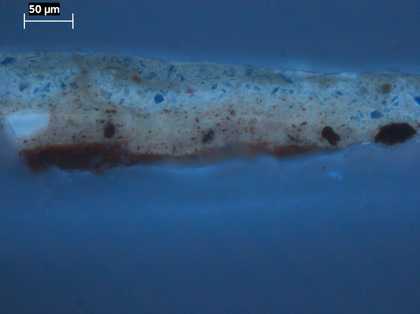

The first application of ground is bright, opaque red, which was scraped hard into the weave of the canvas to fill up the interstices. This was followed up with a fairly thick, smooth, opaque layer of dark salmon pink paint (figs.3–4). It is composed of lead white, red earth colour, chalk and black with the addition of large amounts of pipe clay and quartz as extenders.2 There is no priming layer on the painting.

Fig.3

Cross-section through the sky at the top edge, photographed at x320 magnification. From the bottom: red ground; salmon pink ground; grey paint; blue paint of sky worked into the underlying grey wet-in-wet; varnish

Fig.4

Cross-section through the sky at the top edge, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light. From the bottom: red ground; salmon pink ground; grey paint; blue paint of sky worked into the underlying grey wet-in-wet; varnish

Infrared reflectography (figs.5–6) reveals a few brushed lines slightly offset from the painted design, indicating that the artist started off with a rough, painted outline and kept to it in most of the ensuing process of painting. The X-radiograph confirms the initial planning, with a reserve space for her right hand in the folds of the drapery, and for the trees in the background.

Fig.5

Infrared reflectograph detail of the sitter’s face, shoulder and palm

Fig.6

Infrared reflectograph detail of the wheel

Microscopic examination of the drapery on her left shoulder, where slight shrinkage cracks have occurred, reveals a thin, brown wash, applied on top of the ground and apparently allowed to dry before the colour was applied (fig.7). This wash was probably part of the initial process of outlining the figure and blocking in the very darkest areas of the drapery.

Fig.7

Detail at x8 magnification of drying cracks in the cloak, showing a thin brown wash on top the ground that is visible at the base of each crack

The paint is mainly opaque and was applied wet-in-wet in all areas with well blended strokes, smooth in the flesh tones, brushier in the drapery and background. Impasto is light and was reserved for small details like the highlights on the pearls in the sitter’s hair and gold diadem. Analysis of the colours revealed high quality pigments with very little extraneous matter to extend the paint. As a result, the artist was able to use his paint thinly, confident that its density would cover the ground while allowing its salmon pink colour to provide an overall warm undertone and a unifying glow. This effect has been accentuated over the years by slight abrasion of the paint layers in some areas, such as the white dress. Alterations during painting are minor and are confined to the silhouette of the figure: for example, the shot-silk scarf was extended outwards in a broad curve on the right and nearby the wheel was shifted slightly too.

Other than the brown wash described above, there appears to be no underpainting. What might have been interpreted as a white underlayer beneath the ultramarine blue lining of her left cuff, turned out to be the pentimento described above. The procedure for the drapery was straightforward: three tones of each overall colour were mixed on the palette and then worked into one another on the painting. The pink and purple shot silk scarf, for example, was created by laying down a thin scumble of purplish blue followed by a bright, opaque pink and then a deep reddish purple glaze for the darkest shadows. The pigments used for the mixtures were lead white, ultramarine, vermilion, red lake, Cologne earth, lead tin yellow, earth pigments and black.

There are a few other instances of glazing in the picture. After the face had been worked up in opaque tones, the artist darkened the line between the lips and the shadows of the nostrils with a thin, brown glaze (figs.8–9). For the corners of the eyes he left the ground visible, then glazed over it with the same brown (fig.10). The palm frond was put in after everything else was completed and dry. The artist used complex mixtures of pigments – ultramarine, vermilion, red lake, black and yellows – for the opaque tones of the frond, than glazed over them with copper resinate; when new this would have been bright translucent green but it has turned brown with age. A cross-section from this area suggests the artist may have oiled out the painting, or this part of it, before putting in the palm (fig.11).

Fig.11

Cross-section through the green frond of the palm, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: upper layer of ground; flesh paint of the arm; trace of unpigmented film, which may be the remains of an oiling out layer; green paint of palm; varnish

The overall condition of the painting is good. The entire paint surface is covered with fine, brittle age cracks, some of which relate to stress at the corners. This brittle craquelure is generally slightly raised despite the lining treatment but the paint is secure. There are few losses, mostly at the edges, and little retouching. Many areas contain wide fissured drying cracks (fig.7), which may have been exacerbated if not promoted by the lining. The varnish is a thin, slightly greenish, natural resin.

August 2004