Fig.1

British School 17th Century

The Cholmondeley Ladies c.1600–1610

Oil paint on panel

886 x 1723mm

T00069

This painting is in oil paint on wooden panel measuring 886 x 1723 mm (fig.1). The panel is composed of four horizontal boards of oak, joined with glue at butt joins (figs.2–4). The boards are of unequal width and are thick for a panel from this period: 20 to 26 mm. Examination of the growth rings in the oak produced the following findings: ‘Although no dendrochronological information is forthcoming from this examination it is nevertheless obvious that this panel is unusual. It is not made from straight grained, thin, radial split boards like almost all sixteenth- and seventeenth-century panels. The timber used instead is of quite twisted and knotty grain, is tangentially sawn, and is quite thick. This combination of characteristics suggests a non-professional source for the panel and would be quite compatible with the Tate catalogue suggestion that this is a “local” product from Cheshire.’1

Fig.2

Front of The Cholmondeley Ladies photographed in black and white with raking light from the top to show the arrangement and warping of the boards

Fig.3

The back of The Cholmondeley Ladies photographed in black and white

Fig.4

X-radiograph of The Cholmondeley Ladies

As a result of this unusual construction the panel’s joins have needed attention at various times to remedy splitting: the X-radiograph reveals a very thin, non-original fillet of wood inserted between the two lowest boards at the right edge and held in position with small nails; a long diagonal split across the lowest board was an early development, as are the long nails that were inserted in an attempt to secure it (fig.4).

Fig.5

Cross-section through a ‘comma shaped’ decorative brushmark on the red blanket, photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom: a line of animal glue size, containing a few pigments; chalk and glue ground; off-white priming; purplish pink paint of blanket; red paint of decoration. The inclusion of very large particles of lead white and chalk help give the paint its rough texture.

The ground is a dirty white coat of chalk with traces of red earth colours, black, glassy particles and pipe clays bound in animal glue size; it is up to 50 microns thick (fig.5).2 The opaque, off-white priming on top of the ground varies from 20 to 45 microns in thickness, and is composed of lead white and chalk tinted with black and fine red earth colour, all bound together in oil. The ground, priming and overlying paint have suffered extensive flaking in the past; small losses on average 15 mm long and 5 mm wide occur all over the painting, particularly in areas such as the top left corner where, as the x-radiograph shows, the wood grain is curved.

No distinct underdrawing is visible in infrared reflectography (figs.6–13). It is probable that the artist drew out his design in sketchy dark lines, which are just discernible with the unaided eye in close examination here and there at boundaries; but the easily visible, dark outlines of the compositional elements were done as part of the painting process.

Fig.14

Detail of the embroidery on one of the bodices, showing small detail applied over larger

Fig.15

Detail of a sleeve in slightly raking light, to show small detailing applied on top of larger

The style of this painting is underpinned by a fairly straightforward additive technique in all areas except the faces; additive means that after the laying in of the basic colour in a certain area, details such as shading, glazing and ornamentation were applied on top, often after the first coat of paint had dried (figs.14–15). There is no discernible underpainting, though the X-radiograph shows a build-up of distinctive overlapping brushstrokes, slightly serpentine in form, that were used to produce dense areas such as the dark background. The oil paint is quite lean with relatively large pigment particles, which gives the paint a gritty appearance under magnification. It was stiff enough to retain a distinct, brushy texture on drying. This texture is most apparent in the purple blanket where low relief impasto has been used to delineate the material (fig.16). Scumbles of gritty, off-white paint were dragged across this area after it had dried to create the effect of folds in this quilted fabric.

Fig.16

Detail in slightly raking light of the purple blanket, showing the characteristic, comma-shaped marks in the paint and white paint scumbled on top once the underlayer was dry

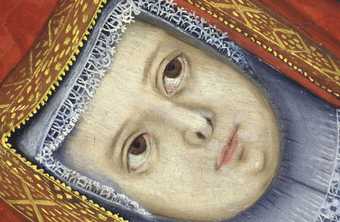

Unlike the additive technique used in most of the composition, the faces and hands were worked up wet-in-wet, with additional detailing on top (figs.17–19). The face of the woman on our left is more dense in X-radiograph than her companion’s; it is possible that the artists reworked this face during painting, though neither this image nor infrared reflectography show the changes he or she might have made.

Fig.17

Detail of the head of the woman on the left

Fig.18

Detail of the head of the woman on the right

Pigment mixtures are as follows: the overlapping strokes of opaque brown tones in the background are made up of lead white, chalk, black, brown earth colours and glassy particles. For the flesh tones the artist made mixtures of good quality lead white, glassy particles, vermilion, charcoal black and yellow.

Fig.19

Detail of the head of the baby on the right

The red blanket contains principally vermilion with small amounts of lead white, red lake, black, glassy particles and possibly red lead. The yellow detailing on the blanket contains lead tin yellow, lead white and glassy particles, while the orange embroidery has lead white, pipeclay, glassy particles, a range of red and sienna earth colours, black and chalk. The white scumbling on the blanket contains lead white with some black, a few glassy particles, pipeclay, cologne earth, dark yellow lake, chalk and a trace of red lake. The presence of ground glass and chalk in many of these colours may be interpreted in a number of ways. These transparent and translucent substances could be used as cheap ways to extend paint, so that the expensive pigments would go further. The glass would also have the additional advantage of making the oil dry more quickly. Both substances would make the paint thick.

The varnish is dammar, which was applied in 1959 after the painting was cleaned and restored at Tate.

August 2004