Fig.1

Marmaduke Cradock

A Peacock and Other Birds in a Landscape c.1704 or later

Tate

T06488

Fig.2

Detail of the peacock and the jay

Fig.3

X-radiograph of A Peacock and Other Birds in a Landscape c.1704‒17

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 761 x 632 mm (figs.1–2). The single piece of plain woven canvas has an average thread count of 14 vertical and 12 horizontal threads per square centimetre. The X-radiograph shows old damage at the top edge (fig.3). Microscopic examination of the remains of this edge shows that it is a selvedge. Cusping is present at the left and right edges but not along the bottom.1

The painting has a glue paste lining, which may date from the early twentieth century. The five-member, softwood stretcher is probably contemporary with the lining, which could have included trimming of the painting’s bottom edge.

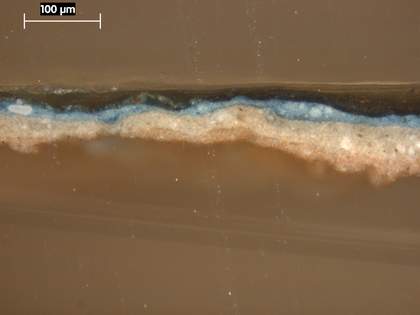

Fig.4

Cross-section through dark, greenish brown foliage in the right foreground, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: coat of animal glue size, stained a deep crimson colour with acid fuchsin in the laboratory to identify its proteinaceous nature; opaque beige ground; opaque fawn priming; grey, green and brown tones applied wet-in-wet; varnish

Fig.5

Cross-section through the sky at the top edge, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: opaque beige ground; opaque fawn priming; pale greenish blue underpaint of sky; brighter blue sky; varnish

The canvas was first sized with a thick coat of animal glue, which is present in some of the cross-sections (fig.4). The ground on top of the size is opaque pinkish beige colour. It is covered over with opaque fawn coloured priming (figs.4–5). No underdrawing was detected using infrared reflectography or with a stereomicroscope.

Fig.6

Cross-section through the peacock’s tail, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: opaque beige ground; opaque fawn priming; opaque red paint; dark red, semi-translucent glaze paint; opaque pink highlight; varnish

Fig.7

Cross-section through the peacock’s breast, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: opaque beige ground; opaque fawn priming; pale, opaque blue paint; dark, translucent blue glaze; varnish with some modern retouching on the right hand side

Fig.8

The same cross-section as in fig.7, photographed at x225 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.9

Cross-section through the red breast of the dove, photographed at x225 magnification. From the bottom: opaque beige ground; opaque fawn priming; sketchy, translucent pink underpaint; opaque red paint; thick, translucent red lake glaze; varnish

Fig.10

The same cross-section as in fig.9, photographed at x225 magnification in ultraviolet light

Examination of the cross-sections indicates that areas of the background were first laid in with opaque grey tones and the sky with pale greenish blue (figs.4–5). The rest of the painting, however, appears to have been done directly onto the priming or on top of very sketchy, translucent underpainting; the visible colours, mainly opaque, were applied wet-in-wet with dabs and overlapping strokes of a soft, well-loaded brush. More detail was added when this paint was dry, followed by glazes of pure translucent colour in some areas, for example the darkest blue and red areas of the doves and the peacock’s head and breast (figs.6–10). This rich peacock blue was created with many thin layers of translucent paint. From their fluorescence when viewed in cross-section with ultraviolet light, the glazes appear to have a resinous binding medium.

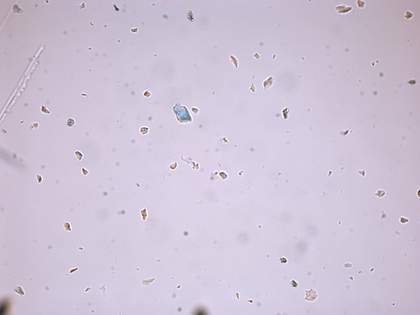

Fig.11

Blue paint from the peacock’s neck mounted in dispersion and photographed in transmitted, polarised light at x400 magnification. Prussian blue appears as the large, translucent blue particle lying north-north-west of the centre of the field

The pigments used in the sky were lead white, black, smalt, yellow ochre, red ochre and finely ground azurite.2 The blue glaze and half-tone on the dove’s blue wigs contain lead white, chalk, Prussian blue and smalt. The darkest blue on the dove’s wing contains gypsum, black, glassy particles, chalk, yellow ochre, Prussian blue and yellow lake. The greenish blue of the peacock’s breast contains yellow lake, smalt, lead white, sienna, red lake, black, Prussian blue, blue verditer and an unidentified translucent filler. The pale yellow highlights on the peacock’s tail contain an unidentified translucent filler, lead white, blue verditer, yellow lake, yellow ochre and chalk. The greenish yellow half-highlights on the peacock’s tail contain an unidentified translucent filler, chalk, black, gypsum, green earth, lead white and blue verditer. The greenish blue glaze on the peacock’s neck contains yellow-brown lake, Prussian blue, smalt, black, lead white and chalk. These is a very early instance of the use of Prussian blue in England, with implications for dating the paintings (Prussian blue was invented in Germany in 1704 and was in use on the continent within the decade). Its appearance under the microscope is different from modern Prussian blue in that it has distinct particulate form; particles are translucent and irregular in shape; blue colouration may not extend throughout the particles (fig.11).

Fig.12

Detail at x8 magnification of the peacock’s thigh and the adjacent background, showing two layers of brown glaze paint overlapping the opaque cream coloured background

Fig.13

Detail at x8 magnification of the peacock’s breast and the adjacent background, showing the blue glaze overlapping the opaque yellow background

Fig.14

Detail at x12.5 magnification of the top edge of the jay’s tail showing drying cracks in the paint, particularly where it extends over the opaque paint of the background

Fig.15

Detail at x20 magnification of lead soap aggregates breaking through the paint on the peacock’s leg

It is clear from examination in infrared light that reserves of space were left for the principal animals in the composition but an interesting technical feature is the adjustments made at their boundaries. After putting in the bulk of the animal in opaque colours, Cradock would take the paint over the boundary with the adjacent background. In places where this was still wet, the contour becomes slightly blended and looks soft to the eye. In dark areas he used thinner, often translucent paint for the outer contours, again lapping over the opaque background colour (figs.12–13). Occasionally he would correct a contour with opaque paint the same colour as the background. One effect of this technique is to give a sense of movement to the animals, whose outlines are slightly blurred. The tendency of paint to become more transparent as it ages by forming lead soaps increases the illusion of movement when the corrected contours start to show through the opaque paint adjacent to them. Another consequence is that some areas of paint have developed small-scale shrinkage cracks from being applied on top of ‘fat’ paint (fig.14). Lead soap aggregates may be seen at high magnification in passages of thick, opaque yellow or orange paint, for example the strokes of dull orange paint down the left side of the peacock’s right leg (fig.15).3

August 2005