Fig.1

Anthony Van Dyck

A Lady of the Spencer Family c.1633–38

Oil paint on canvas

2076 × 1276 mm

T02139

Fig.2

Detail of head and shoulders of A Lady of the Spencer Family c.1633–38

This painting is in oil paint on canvas measuring 2076 x 2176 mm (figs.1–2). The single piece of coarse, plain-woven, linen canvas has 10 horizontal and 13 vertical threads per square centimetre. The threads are irregular in thickness. The painting now has a glue-composition lining and a non-original, five-member, pine stretcher; both lining and canvas appear to date from the late 19th or early 20th century. The tacking edges have been removed at some time in the past, leaving the top edge of the canvas rather uneven. Cusping is present along all four edges in varying degrees, indicating that there has been no significant trimming of the composition.1

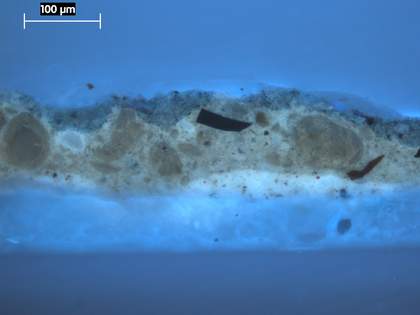

Fig.3

Cross-section taken from the darkest blue passage of the skirt of the blue dress, 411mm from the left and 872mm from the cut edge at the bottom. Photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom: pink ground; buff coloured quartz priming; dark blue paint of dress; modern synthetic varnish

Fig.4

The same sample as in Fig.3, photographed at x320 magnification

Fig.5

The same sample as in Fig.3, photographed at x320 magnification in ultraviolet light

Fig.6

Cross-section taken from the dull greenish brown background at the right edge, photographed at x200 magnification. From the bottom: pink ground; buff coloured quartz priming; paint of background

Fig.7

Detail at x8 magnification of the priming left visible in stiff paint in the sitter's right sleeve and cuff

The ground is opaque, pale, dull pink and has been thinly applied, which allows the weave texture to show. This is now emphasized by old losses of paint and ground from the tops of the coarse canvas weave, through abrasion. The priming is semi-translucent and buff coloured with a gritty texture; the principal component in this layer is quartz (figs.3–6).2 The ground and priming are bound in oil, as neither gave a positive result for protein when the cross-section was stained with acid fuchsin. The priming colour was left visible deliberately in some areas, for example in her right hand and cuff (fig.7).

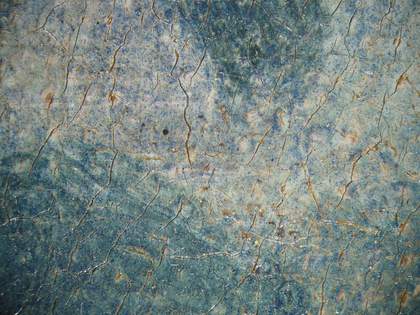

Fig.8

Infra-red reflectogram of the reinforcing lines in the figure

A dark painted line reinforces part of the figure (fig.8) but this appears to have been done during the painting of the image rather than as preparatory underdrawing. Nothing similar can be seen elsewhere.

Fig.9

Detail at x8 magnification of wet-in-wet brushwork in a green leaf

The sky and background were applied in a single, opaque layer wet-in-wet, showing the artist’s virtuoso skill at constructing tonal modelling with this direct and immediate technique. The brown curtain is modelled in what appears to be a single layer of opaque, wet-in-wet paint with the decorative pattern applied directly over it. The foliage was laid in dark tones and the highlights then added on top using the same opaque, wet-in-wet technique (fig.9).

Fig10

Detail at x8 magnification of wet-in-wet brushwork in the sitter’s right cuff

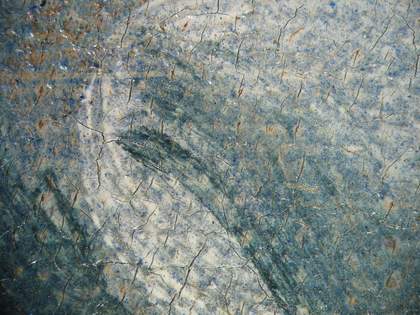

Fig.11

Detail at x8 magnification of wet-in-wet brushwork in the folds of the skirt. Note the two different blues: ultramarine and indigo

Fig.12

Detail at x8 magnification of wet-in-wet brushwork in the skirt, with ultramarine glazing

Fig.13

Detail at x8 magnification of wet-in-wet brushwork in the skirt with ultramarine glaze over opaque underpaint

Most of the dress, however, was dead coloured in opaque shades of blue mixed up from indigo, black and lead white: dark greyish blue, two shades of pale blue, and white, all worked together on the canvas wet-in-wet. When the paint was dry the highlights and mid-tones were glazed with ultramarine mixed with quartz, lead white and black. Indigo was used to glaze some of the shadows (figs.10–13). It must have looked resplendent and a far cry from the faded, abraded image we see now. The ultramarine glazes are now present only in the troughs of the brushwork and the indigo in the dead colouring has faded at the surface to about half its original intensity.

Fig.14

The sitter’s left eye photographed at x8 magnification

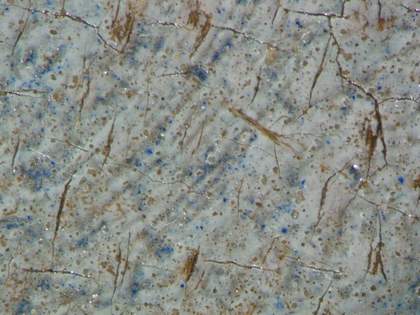

Fig.15

Detail at x16 magnification of blue pigment in white of sitter's eye

Fig.16

Detail at x12.5 magnification of lead soaps in blue highlight of left sleeve

The sky was mixed from lead white with smalt, earth colours, black (not bone black, probably charcoal black), and cologne earth with a trace of vermilion. Opaque green foliage was mixed from a copper green, lead white, terre verte, chalk, yellow and red earth colours and yellow lake. The mustard yellow curtain glazed with brown contains earth colours, cologne earth, smalt, quartz and gypsum. The whites of the eyes have an admixture of ultramarine or strongly coloured smalt in the lead white (figs.14–15). The flesh paints were mixed from lead white with a charcoal-type black, red lake, opaque red, opaque orange and opaque yellow particles. Blue pigment is also visible in the foreground, beige coloured paint. A ringlet, which sat on the sitter’s left shoulder has been painted out. The paint in many areas of the composition has developed lead soap aggregates (fig.16).

September 2020