As a conservator, I occasionally come across opportunities to work on the collection of one artist, which is something I always greatly relish. This is because you get to really know the artist’s working techniques and materials, and feel a sense of connection with them as you get to know their work better.

The experience of conserving Graham Sutherland’s sketchbooks allowed a fascinating insight into the working methods of the artist, as well as being a good example of how conservators make decisions of when to treat damage and when to leave it alone.

Watch the Animating the Archives video which looks at the conservation and digitisation of Graham Sutherland’s sketchbooks and the importance of archive collections to our understanding of artists’ practices.

This film file is broken and is being removed. Sorry for any inconvenience this causes.

Archives & Access Project: Animating the Archives – Graham Sutherland Sketchbooks

What I’ve discovered

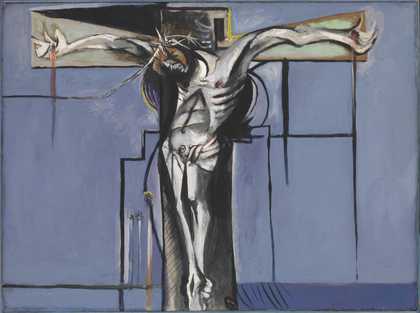

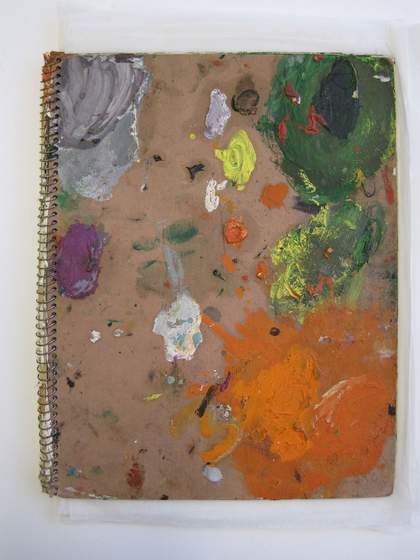

Some artists choose to use the same style of sketchbook throughout their careers, but Sutherland used a very wide variety of books, ranging across many sizes and formats: wire spiral-bound, sewn, with perforated tear-off pages, cheap lined notebooks, quality artist’s sketchbooks… Often the covers had been torn off or sometimes showed evidence of having been used as a palette or testing area.

Cover of sketchbook with paint applications© The Estate of Graham Sutherland

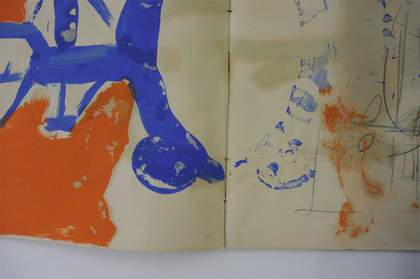

Inside, there was frequently a similar rough-and-ready approach: extra pages stuck in and additional objects glued to pages, slashes that extended down through several pages, dog-eared corners, and numerous tears and creases. Most notably, Sutherland frequently used thick paint applications and closed books before the paint had dried: throughout the sketchbooks there were many pages that were stuck together by the paint layer. In several places, these pages had then been forcibly separated, resulting in tears which could make the image appear very confusing as this could expose areas of the page below.

Double page showing torn area at centre bottom, due to forced opening of stuck pages© The Estate of Graham Sutherland

Close-up of damaged area, this time with white paper inserted below page on left side to show extent of tears© The Estate of Graham Sutherland

Some stuck pages proved impossible to separate, and it would have caused more harm to attempt to intervene. However, the example above shows how such damage made some images rather confusing and unreadable, and for this page it was possible to gently release the torn and stuck area seen on the right hand side, and flip it back to the left in order to complete the image.

The same area, following repair© The Estate of Graham Sutherland

As mentioned above, the stuck pages are indicative of how Sutherland worked; we can presume quickly and not allowing pages to dry before moving on to the next page.

Similarly, some of the dog-ears and folds around the edge of the paper reveal information about his working style: many have paint extending over the folds, showing that Sutherland chose not to straighten up pages or unfold corners before he applied media. This is something that as conservators, we respect and leave as it is; as he must have chosen it to look this way (whether deliberately or unthinkingly).

Corner showing how paint splashes were applied after fold occurred© The Estate of Graham Sutherland

Edge of page showing boot-print

© The Estate of Graham Sutherland

Looking through the sketchbooks, we get a privileged insight into how Sutherland worked in his studio. Another page shows a dirty mark which appears to be a boot-print at the edge of the page. We get the impression of someone who worked perhaps in a fervent manner and was not precious about keeping his working drawings flat and pristine.

In conserving this collection, I respected this and was careful to ensure that I preserved all evidence of his working methods but at the same time made sure that these objects are safe for digitisation.