This work has a history. Helen Douglas has been engaged with nature and with narratives for much of her life. Her formative years were spent in the Scottish Borders in a farming community, and she returned to live there as a working artist. Her chosen medium for embodying her expressive visual narratives has for many years been the photographic image used in conjunction with the book. Her works have been collected and exhibited nationally and internationally, and her achievements in the field of artist books are manifold.

One example of a book by Douglas is Unravelling the Ripple (2001), which is a direct predecessor of The Pond at Deuchar in that it gathers together photographs that record the viewer’s downward gaze in a continuous sequence. In Unravelling the Ripple the viewer is poised over the boundary between water and land where the sea meets the shore. Before this most of Douglas’s works were visual narratives in the form of relatively inexpensive paperbacks, published in hundreds of copies under the imprint Weproductions; they were frequently collaborations. However, taking advantage of digital printing, from 2006 Douglas began to publish works in smaller editions, many of which questioned the familiar structure of a book or codex. Indeed, she has recently seized upon the historic hand scroll form to embody her ideas.

The origins of this interest may go back as far as 1977, when she made the accordion book Clinkscale with Telfer Stokes. Much later, though, Douglas spoke of a mode of composition that was particularly significant in the development of her 1997 paperback book Between the Two. She began to place the components of this evolving book on the floor, working on and across it. ‘Trusting in the unravelling and connecting of these areas across the floor I realised in the making that I was shaping the material into phrases, as breaths from the chest, as open arms’ spans of about six to eight pages’ (Journal of Artist’ Books, 12, 1999). This concept of ‘phrases’ became an important element in Douglas’s work, and although at first the phrases were edited to fit a signature of pages within a conventional codex book, she went on to realise that the scroll form was sympathetic both to her discovery and to the reading of visual narrative, finding similarities in Chinese precedents.

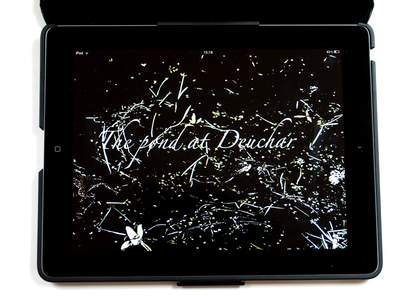

In 2004 Douglas published Illiers Combray. This book grew out of experiences in the French town celebrated by the writer Marcel Proust, and even has echoes of his way of working with ‘paperolles’ (in which paper scroll additions were pasted into his manuscripts). Although the book is in a concertina format, the folds immediately open to reveal visual ‘phrases’ spread over several individual openings. From this point the scroll, either folded or rolled, became an ever more significant part of Douglas’s way of working. In 2010 Douglas made the hand scroll poempondscroll in which images of the pond where she lives were linked seamlessly, phrase by phrase, into a long narrative. This work led directly to The Pond at Deuchar in 2011, which was digitally printed on a Chinese paper and measured over fourteen metres long. The continuous digital photographic files used for printing this hand scroll have been directly transposed into the digital e-scroll that you have traversed. This process has thereby made something formerly published, of necessity, in limited numbers into an amazingly accessible and affordable work of art, thereby remaining true to the ‘democratic’ origins of artist books.

Yellow Pages telephone books used to bear the slogan ‘Let Your Fingers Do The Walking’. Today, instead of having to use both hands to unroll and roll up a hand scroll in order to read or view it, it is possible to let your fingers move the e-scroll along, almost, in this particular instance, like trailing them in the water over the side of a boat. We can touch, probe, and foster our curiosity by spreading our fingers to enlarge the image, thereby facilitating a plumbing of the depths of the e-scroll and the world it conjures. Let your fingers do the looking.

Upon embarking on your spatial and temporal journey across The Pond at Deuchar you will first have to negotiate your way past a pop-eyed speckled sentinel, the first of several frogs and toads that swim, glide, or lurk over the dark bed of the pond. This bed is layered with sunken brown fallen leaves, while above it the pond’s surface is interrupted by the green leaves of living water plants and sparks of colour from flowers. A new development in the narrative is the appearance of calligraphic skeins of toad-spawn, the consequences of earlier frolics. As the season progresses, the spawn gives rise to a wriggling punctuation of tadpoles, dancing with their shadows, and joining other denizens of the pond, including water spiders, pond skaters, a newt, larvae and maybe water crickets in a ferment of fertility. Throughout the scrolled narrative the pond is embroidered by intricately engineered images of vegetation, sometimes above the pond, sometimes on the surface, sometimes reflected, sometimes underwater, often disturbed by exquisite ripples of light. In one passage the dark depths of the pond are intermingled with reflected blue sky, while the intense blue of a damselfly heralds the appearance of tiny specks of reflected blue speedwell, all contributing to a dance of light and colour, surface and depth.

The e-scroll and the iPad are clearly sympathetic supports for a flowing filmic narrative, and this work is a significant forward step in the evolution of artist publications. While the essence of the pond at Deuchar has been transubstantiated into this e-scroll, and stands as a cradle for the life cycles of many diverse life forms that co-exist, though perhaps not always peaceably, in a specific ecology, it might also have microcosmic and metaphoric parallels with our own society.

Clive Phillpot

August 2012

Clive Phillpot is a writer, curator and former librarian at Chelsea College of Art & Design, London, and former Director of the Library at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.