Seeking to bring together leading scholars in the UK, USA and Europe and to encourage new research and fresh perspectives, the project hosted four day-long workshops, often in partnership with academic institutions. The topics addressed included exhibitions of American art during the Cold War, the idea of the American canon, the role of the market in the making of American art, and the complexities of collaborative relationships and artistic processes.

The project culminated in a major international conference, titled ‘Border Control: On the Edges of American Art’, held at Tate Liverpool in May 2017. With twelve speakers from around the world, the conference focused on the ideas of borders and limits, and the crossing of these.

Find out more about the workshops and conference and read the abstracts.

Border Control: On the Edges of American Art

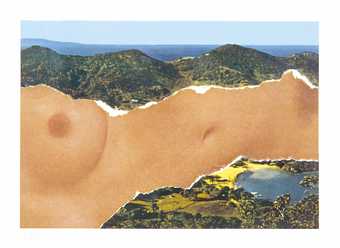

Ellsworth Kelly

Saint Martin Landscape (1979)

Tate

Major international conference

Thursday 25 and Friday 26 May 2017

Tate Liverpool

Convened by Julia Tatiana Bailey (Tate) and Alex J. Taylor (University of Pittsburgh)

Supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art

This major international conference led by Tate Research was a two-day event bringing together historians of art and visual culture to share new scholarship exploring the crossed boundaries and expanded limits of art from the United States. Border Control: On the Edges of American Art was presented as the culmination of the three-year Tate Research project Refiguring American Art and coincided with a related display at Tate Liverpool.

Special Relationships: American Artists and their Collaborators

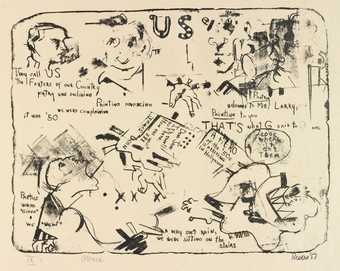

Larry Rivers and Frank O’Hara

1 1957

Lithograph on paper

From Stones 1957–60

© The Estate of Larry Rivers

Courtesy the Estate of Frank O’Hara

Academic workshop

Friday 26 August 2016

Convened by Alex Taylor (Tate) and Matthew Holman (University College London)

Response by Joanna Pawlik (University of Sussex)

Presented with the support of the Terra Foundation for American Art

With the assistance of the SAVAnT (Scholars of American Visual Arts and Text) research network, University of Sussex

The waves have kept me from reaching you’, wrote Frank O’Hara in his poem The Harbormaster (1954). Addressed to his collaborator and lover Larry Rivers, whose work together culminated in the ten-part print series Stones (1957–60), O’Hara cast their special relationship as one defined as much by distance and estrangement as by creative kinship. Artistic collaborations might make possible artworks unimaginable by an individual maker, but they are also usually a messy business, strained by competing procedures and visions, and often wracked by interpersonal friction and inequality.

The complexities of collaborative relationships and processes were the focus of this event, with participants exploring what kind of social, critical or theoretical concerns have shaped artistic partnerships, and how such projects have challenged the authority of the individual artist and the inviolability of the modernist medium. With the support of the SAVAnT research network at the University of Sussex, which seeks to foster dialogue between scholars in American studies and the history of art, the workshop focused on collaborations that have brought the visual arts into direct contact with fields including literature, music, dance, theatre, film, fashion, design and architecture. Alluding to the ‘special relationship’ between the United Kingdom and the United States, itself a contested and sometimes unequal union, the title of the workshop also gestured toward the geographical and political traversals made possible by collective artistic production, by which post-war artists have expressed affinities that transcend the nation.

Visible Hands: Markets and the Making of American Art

Cildo Meireles

Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project (1970)

Tate

Academic workshop

Friday 22 January 2016

Convened by Alex Taylor (Tate)

Response by Marina Moskowitz (University of Glasgow)

Presented with the support of the Terra Foundation for American Art

The ‘invisible hand’ of the market, an idea first coined by enlightenment philosopher Adam Smith, has become a fundamental principle for advocates of free market capitalism. Smith’s famous turn of phrase disembodies the sensations of sight and touch, but by restoring their primacy in this workshop’s title, his metaphor acquires new possibilities for tracing the influence of the market on works of art. Far from neutral or natural creations, markets – like artworks – are forms that are always composed and manipulated according to the interests of their makers.

This event brought together papers that explored the role of the market in the circulation and exchange of American art, and its visual and theoretical impact on the work of art itself. How did, for instance, the scale or materiality of works of art concretise their entanglement in economic systems? How are the dynamics of supply and demand, boom and bust, or other market phenomena apparent within particular artistic practices? How did critics and curators absorb the principles of the market in its approaches to the history of American art? What were the transnational ramifications of these intersections between art and economics? With scholarship concerning works from the late-nineteenth century until the late twentieth century presented, speakers engaged questions such as these in order to explore the role of the market in the making of American art and art history.

The workshop occurred as part of a series of independent but related events organised by Maggie Cao (Columbia University), Sophie Cras (Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne) and Alex J. Taylor (Tate) that are intended to explore economics as an emerging field of art historical inquiry. The second event in this series is Art and the Monetary at the Society of Fellows in the Humanities at Columbia University, New York.

Blind Spots: Revisiting the American Canon

Academic workshop

Tate Liverpool

Friday 9 October 2015

Convened by Alex Taylor, Terra Foundation Research Fellow in American Art, Tate Research; Isobel Whitelegg, Research Curator, Tate Liverpool/LJMU; Sonya Dyer, Curator, Public Programmes, Tate Britain/Modern; and Stephanie Straine, Assistant Curator, Tate Liverpool.

Presented with the support of the Terra Foundation for American Art and Liverpool John Moores University

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Tate’s collection and display of twentieth century art from the United States was its first move beyond the bounds of British and Western European art. As such it might now be understood as the inaugural step in an ongoing process of strategic internationalisation. Like many other modern and contemporary museums, Tate has in recent years expanded a North Atlantic-centred canon in order to produce a multi-centred global history of art, correcting past oversights and omissions. Despite these later geographical expansions to the art historical reach of the museum, the art of the United States retains a distinct primacy. In line with its central position in post-war history, it both inherits the advantages of that stable foundation, and invites a process of revision in which the very idea of an American art is subjected to various spatial, linguistic and political expansions.

At a moment when the value of embracing a more diverse geographical and critical terrain has become widely accepted, this one-day event returns to the context of post-war American art with the aim of reconsidering its place within the museum and the academy. This event was convened in the context of two parallel exhibitions at Tate Liverpool, each deploying a contrasting curatorial strategy in order to re-approach art and artists that might be considered to be canonical. Using artist Glenn Ligon’s perspective as its guide, Encounters and Collisions revisited the history of post-war American art in order to create a personal museum that emphasises queer and African-American experiences while acting as a subjective reading of major movements such as minimalism, abstract expressionism, and pop. Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots sought to restore doubt, inconsistency and complexity to the trajectory of an artist widely taken to be the very personification of the geopolitical dominance of abstract expressionism in the Cold War era.

Marshalling American Art: Exhibiting Ideology in the Cold War

Friday 1 May 2015

Convened by Alex Taylor (Tate) and Julia Tatiana Bailey (University College London and Tate)

Response by Jody Patterson (University of Plymouth)

Presented with the support of the Terra Foundation for American Art

In 1948, under the economic recovery programme known as the Marshall Plan, Europe was the recipient of some $17 billion in aid from the United States. Ostensibly aimed at spurring economic growth, the initiative also sought to cement American political influence in the region, in line with the Truman administration’s wider policy of containment to prevent the spread of communism. In the decades ahead, and especially as the politics of the Cold War intensified, the cultural influence of the United States emerged as an increasingly visible and contested issue across Europe and the United Kingdom.

Exhibitions provided one crucial medium for the advancement of this strategy and a forum to debate its legitimacy. Whether in response to large and high-profile touring shows, or to smaller displays at commercial galleries, the reception of post-war American art was frequently refracted through the prism of cultural imperialism and ‘Coca-Colonisation’. Beyond art exhibitions, these were debates that found further visual expression in the wide range of fairs and trade events through which Cold War ideology was put on publicdisplay. This workshop brought together a range of papers that represent new research into exhibitions of American art and visual culture during the Cold War.