An overview of the works in the exhibition

The Gilbert & George exhibition occupied the whole of the fourth floor at Tate Modern, including the café spaces and the large concourse area that includes the escalators. Some of the artworks consisted of collections of tiny postcard-sized black and white photos, others, huge arrays of large digitally printed panels. Most of these are housed in anodised black aluminium frames, behind Perspex. Sometimes the frames are butted against each other to form one enormous image, sometimes they are separated.

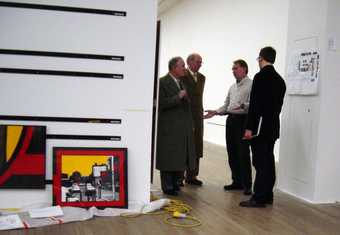

Gilbert and George next to hanging rails for a photo piece

Typical crate on arrival

Hanging such a large exhibition was a challenge. Normally a fortnight is allowed for the installation of an exhibition that fills ‘one module’ – approximately half of the fourth floor of Tate Modern. This exhibition spanned two modules and the concourse, and had to be installed in three weeks.

Condition checking each artwork

Conservation had to check the condition of the many loans as they arrived, and liaise with the couriers from the lending institutions to complete condition reports. In effect, it turned out that many of the pictures had to be checked hanging on the wall, after installation. With seven pairs of art handlers hanging as fast as they could safely go, it was not possible for two pairs of conservators to keep up with them.

Installing the artworks in the gallery

Some of Gilbert & George’s works measure as much as 15 metres across. Fortunately, they consist of several much smaller individually framed images, making them easier to transport and install than other larger works. However, there are still complications inherent in the process. One of the hanging methods for these works involves ‘keyholes’ in the back of each metal frame, into which screws set into the wall have to fit.

If the frames are to butt snugly up against each other, the bottom row of panels must be hung first, then the row above, and so on upwards. Drilling holes in the wall creates dust. Most of this can be caught in an envelope taped to the wall below the drill. However, some dust inevitably escapes and drops down past the row of pictures already hung below. Since the Perspex is fitted fairly loosely in the frames, any dust falling into the rebates will soon find its way inside. A vacuum cleaner with a soft brushed head is used to clean up any dust.

Peeling back low-tack film, to find broken glass

High off the floor on a Genie machine

Extant materials between the perspex and the image

As conservators inspected the different panels loaned to the exhibition in order to write their condition reports (4,200 in total), a variety of materials were already found to have worked their way between the Perspex and the image. Plaster dust infiltrated from previous hangings had tended to move to the centre of the frame, and there was gentle abrading to both the inside of the glazing and the surface of the image.

In addition specks of black foam padding from the travelling cases and granules of white expanded polystyrene from the thermal insulation of the cases were found. Depending on the colour of the image in each case, these specks were either camouflaged or accentuated. In some instances, a more thoughtful case design had prevented this problem, and it was clear that where the works had been wrapped with polythene; this had also worked well.

Monitoring the environment of the exhibition space

During preparations for the exhibition, conservators took measurements of the temperature and humidity in the concourse areas at Tate Modern, around the escalators and the café. The findings showed that conditions in the centre of a large well designed building are remarkably constant. Tate was able to exhibit artworks in these areas without qualms.

The big problem for the conservation team was the build-up of fine dust on the glazing, from the passage of the large number of visitors Tate Modern receives. This was dealt with by a thorough cleaning regime.