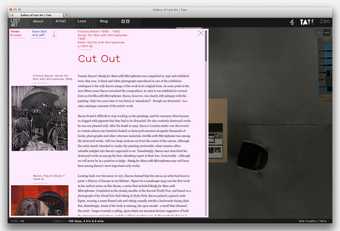

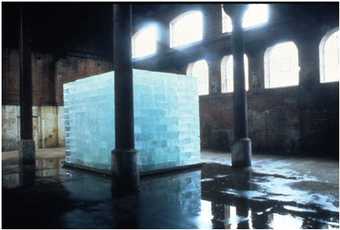

Set visually in a warehouse-like space through which the visitor could wander at will, The Gallery of Lost Art presented the stories of loss through documents and films laid out on different tables (or, when the scale of the missing works warranted it, on the floor). Alongside these materials were captions, sound clips and links to other resources. The virtual space thus offered the visitor a place for engagement, private study and reflection. Digital images were transformed into likenesses of research material of the sort that might have been accumulated by someone investigating what had happened to the missing artworks. Photographs and computer printouts were shown lightly crumpled or mounted on dog-eared paper; press cuttings were arranged casually spread or out stacked in untidy piles; and throughout the site were signs of research under way: people bent over the various tables, card files and folders with bulldog clips and yellow Post-It notes, and open laptops (a home for the project’s films made by Tate Media). The invitation to new visitors to join these researchers as they studied documents and read associated texts, or while they listened to audio tracks and viewed films about the missing works was clear.

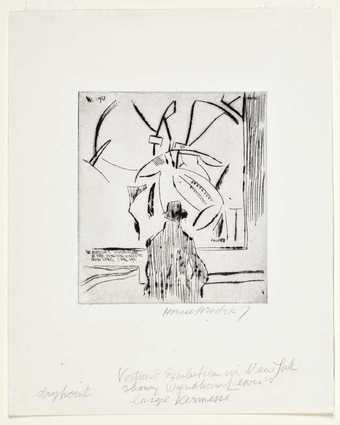

Although the online exhibition presented itself as a site for restoring to consciousness particular examples of modern art that had been lost, the project also explored the subject of cultural loss more generally. The conventional ways in which artworks can be lost – fire, war, attacks and neglect, for example – were all examined. But loss was also seen as varied in nature: both temporary (in the case of stolen works) and permanent; intentional as well as accidental; and the result of deliberate decisions made by artists and not just of events beyond their control. Loss was seen as a matter of deep regret, but also sometimes as a source of creativity, with damaged or destroyed works taking on a second life as ‘relics’ or documents of their existence that inspired artists to create new art. Some of the works featured were well know in part because they were lost, though most were at risk of being forgotten.

Museums such as Tate normally tell stories through the objects they have in their collections. This project posed the challenge of focusing on works that a museum could never own – they were after all destroyed, or missing, or even, in two cases, never completed – but that are nonetheless part of the narratives that such institutions, with their aim of presenting the different histories of modern and contemporary art, could and arguably should tell. With its specially commissioned films and texts, the website, which lasted for only one year before, fittingly, becoming ‘lost’ itself was one response to this challenge; a full length book (Jennifer Mundy, Lost Art, Tate Publishing 2013), with expanded narratives about the forty case studies, was another.

The exhibition generated over nine hundred features in print and online media, built and sustained through the steady release of additional ‘tables’ each week for the project’s first twenty weeks (the project launched with only half the site revealed). It received 102,182 unique visits, leading to 616,049 page views, by people living in 153 countries and 6,700 cities. It has been estimated that 3.4 million people were potentially aware of the exhibition through the proliferation of reviews and mentions. In 2013 the site won an Honourable Mention at the Webby Awards, and the following international awards:

- SXSW: Interactive Art Award

- Best of Web: Digital Exhibition Prize

- Museums and Heritage: Innovation Award

- Design Week Awards: Interactive Design Award