Adrian Fogarty is a trained engineer and works directly with many artists on the fabrication of their artworks. He is often presented with an idea which he then translates into something that can be realised. He is an expert in electronic devices and motors who helps us within time-based media conservation at Tate to understand the workings of particularly complex equipment. Often, one of Adrian’s main tasks when working with Tate is to improve the robustness of a device so that it can withstand the ambitious performance that Tate requires, running for 70 hours a week for anything from three to twelve months. Adrian also helps us repair and maintain electronic-mechanical equipment and has been fundamental in training staff to troubleshoot and maintain slide projectors.

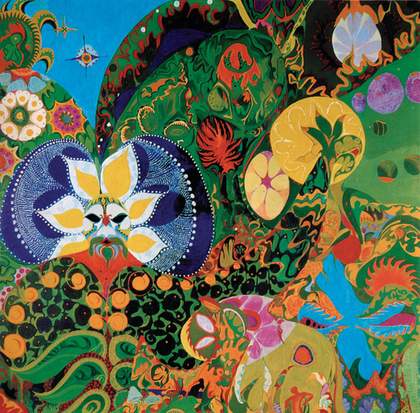

Over the years, Adrian has been involved in the production of a number of artworks which he has designed or custom modified, some of which later became part of Tate’s collection. My first encounter with Adrian was during the installation of the exhibition Summer of Love at Tate Liverpool in 2005 where he worked with Gustav Metzger on Liquid Crystal Environment (T12160), which originally provided the visuals to accompany a live performance by The Who in 1965. For the reconstruction of this performance, Adrian designed a device that could change the temperature inside the slide projector, regulate the brightness of the lamp and rotate a polarising filter. All of these elements are employed to alter the appearance of liquid crystals enclosed in a slide mount so that their aggregate state changes between liquid, solid and crystalline, and consequently creates a truly psychedelic projection. Gustav and Adrian worked together constructing a sequence that would allow subtle changes at first, which developed to a point where the slide projectors responded to each other. Adrian is now working on ‘Version 5.0’ of the system: the latest update in the evolution of the work and its technical invention. The first prototype for this project dates back to 1998.

Reconstruction of Gustav Metzger’s Liquid Crystal Environment (T12160) in 2005

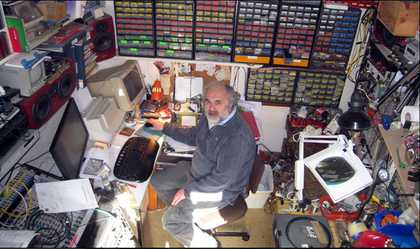

Until the early 1980s Adrian specialised in the engineering of oceanographic scientific instruments and he worked on tools such as the current meters used by oil companies to plan the positioning of oil rigs in the North Sea. Consequently he started working with computers as early as 1974, and simple but effective programming remains one of his core skills combined with the design of printed circuit boards. When asked how he ended up working in the arts, he recalls that a good artist friend of his, Roberta Graham for whom he made equipment and helped create slide tape works, introduced him to an artist’s collective known as the London Film Cooperative. Around the same time he designed a synthesizer and produced the sound effects for a Derek Jarman (1942–1994) film and all of a sudden he became one of the default technical experts in the London arts field in the 1980s. This has continued to the present today, although there are periods when the phone goes quiet. Adrian has never advertised his services and does not have a website. Adrian’s lab, in his attic at home, has a footprint of just three by two metres and yet contains a milling machine for mechanical parts, a sound and recording studio, and a micro-soldering station to produce electronics for which he sometimes has to turn the kitchen into a chemistry lab to etch printed circuit boards.

Adrian Fogarty in his multifunctional lab

Adrian knows his limits with the technology he works with, and fully respects these when it comes to the complexity in which consumer electronics have evolved; for example there is no screw on a Kodak S-AV 2050 slide projector that he does not know intimately; but he was most reluctant to undertake the dismantling of a Kodak Ektapro Cine 9020 slide projector. Tate had recently purchased a large number of these second-hand and soon realised that they were all programmed with an auto soft-fade feature that could not be overwritten. The only option to overcome this was by replacing the microprocessor chip which meant stripping the whole projector for which I badly needed Adrian’s assistance. We were both out of our depth but succeeded and have since trained Tate’s time-based technician to carry out this modification. It is always a revelation to master a task that we both doubted was possible; it broadens our horizons and reinforces the trust in our expertise. This in itself is one of the greatest paybacks in our job.

Adrian Fogarty working with time-based media technicians Fergus O’Connor and Jack Friswell on the upgrade of the Kodak Ektapro Cine 9020 slide projectors

Adrian only accepts jobs that he is comfortable with and when in doubt he presents a thorough feasibility study to inform his decisions which he then submits as a written report. I do not know whether Adrian actually likes writing reports but he certainly produces a lot of them. Such is their precision, and the clear operation instructions and insights they include, that we use them as manuals. Adrian has never stopped taking his designs further, just out of curiosity. Microchips are growing increasingly smaller and more powerful, and this frees up valuable space on his tiny PCBs for new features. When visiting his lab, I can make out the remains and prototypes of every project we have worked on together.

Adrian is great fun but also very inspiring and motivating in the way in which he ponders problems out loud and brainstorms in a unique fashion. He always involves museum technicians and conservators in this process, asking for our opinion, so that whatever is the ultimate conclusion, it is the result of teamwork. Working with somebody like Adrian often makes us notice how we can improve on our own teamwork, and also on how little it takes to share our experiences and success together.