The Map of Interactions is a document that aims to provide an understanding of the networks that exist both internally and externally to Tate. These networks are critical in supporting the institution’s ability to activate performance artworks in the collection and have been developed in practice to create a tool that maps a range of interactions.

This tool is part of an integrated approach, which includes two other tools – the Performance Specification and Activation Reports. The Performance Specification is written with the goal to assist in the identification of the core aspects that must be transmitted when activating the performance. This document is in permanent revision, with changes being triggered by new information emerging from Activation Reports. The Activation Report captures new information in each instance that the artwork is brought from its dormant state through to its activated state. It intends to capture the characteristics of activated artwork at least once during the period in which it is installed, acknowledging moments of change and decision-making dynamics in the activation of the work. These two documents feed into the construction of the Map of Interactions.

The identification of networks through the Map of Interactions is essential in facilitation the understanding and assessing areas of vulnerability around each interaction. The Map of Interactions also facilitate the development of strategies to address any perceived risk of loss of knowledge and dissociation, addressing any potential risk to activation and transmission. Understanding those risks is critical for performance artworks and other artworks with performative features, which tend to remain dormant in storage and up until they are activated.

Tania Bruguera

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 (2008)

Tate

Both human and non-human actors, such as objects, technology, infrastructure, or nature, are considered in the creation of this network. The acknowledgement of the importance of non-human actors, besides allowing for a deeper understanding of their influence, flags possible risks in the structure of care of performance works. If we take the artwork Tatlin’s Whisper #5, created by Tania Bruguera in 2008 (fig.1), as an example, we can see how much of the survival of the artwork as a live action is based on the interaction between humans and nonhumans – in this case, horses.

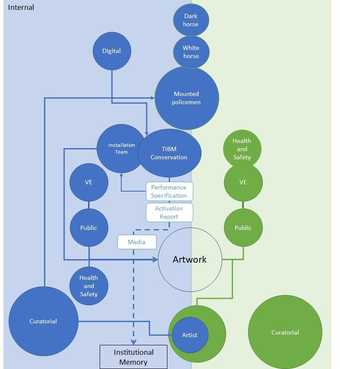

Fig.2

Example of the Map of Interactions for Tatlin’s Whisper #5

This performance involves two mounted policemen in uniform (one on a white horse and one on a black horse) that are brought into the exhibition space. They patrol the space, guiding and controlling the public by using a minimum of six crowd control techniques. These include actions closing off the gallery entrance or entrances, pushing the audience forward with lateral movements of the horses, manipulating the audience into a single group and encircling it to tighten the group, frontal confrontation with the horse and breaking up the audience into two distinct groups. The Map, in this case, places the artist in the centre of the work, with the primary network identifying being the Mounted Police and the actors of the Police Officers and Horses (fig.2).

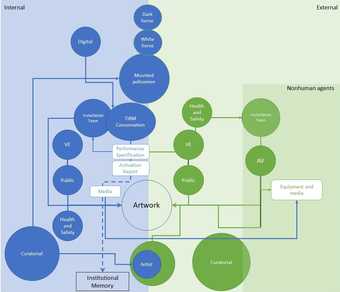

Fig.3

Development of the Map of Interactions for Tatlin’s Whisper #5 following the artwork’s display in 2017

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 exists on this strong reliance on this network. The Map allows the rarity of the interaction to be captured and for these networks and the relationships to the artwork to be maintained. The rarity presents a challenge for conservation with respect to ensuring that the knowledge of such networks is monitored, understood and preserved given the infrequency of the activation. When the work was lent in 2017, this made visible the importance of having a white horse performing the work, as the artist describes the colour of the horses as ‘a symbolic element’ of the work. The inability to source a white horse spoke to this rarity and led to a shift in what was requested to be shown, with a request for video documentation. The video documentation produced by Tate for internal purposes was used within a timeline, to show ‘what the artist has done’, and was presented alongside four other videos of her work. This was the first time documentation was shown, and the artist made it clear that this was only in the context of a chronological representation of her oeuvre.

Documentation was not intended as a replacement of the work, but as an index of the artist’s practice. This change, nonetheless, created new dependencies in the artwork’s network (fig.3) and might influence how the artwork will be displayed in the future. This example not only highlights the possibilities for change in the interactions that sustain an artwork, but it also makes clear the need to remain in a dialogue with the artist regarding the work. This case study also makes explicit the potential of loans in destabilising networks of interactions, which, in turn, might reveal possible futures of the work and multiply the instances of its activation.

In the case of future activations, the Map of Interactions can be reflected on to assess the current or perhaps changing vulnerabilities with the networks identified. This will allow the precarity of networks to be further understood and updated. Depending on the activation, and as we have seen with Tatlin’s Whisper #5, new networks may appear or change. Information management is, after all, at the core of this whole process, which dwells in a practice of preserving Tate’s institutional memory about these works.