Paintings often appear little changed from their original state. However, in reality, oil paintings yellow and darken as they age and cracks can form in the paint surface. These changes are normally accommodated by the viewer, often unconsciously, but some localised changes that develop over time can be visually interrupting.

Richard Hamilton’s attitude to changing works

Richard Hamilton has spoken about changes in his work. In early paintings he primed the support with a hardboard primer. It was not a stable product in terms of its colour as it was intended to be painted over. Hamilton, however, left it exposed in many areas and indeed it has discoloured. This is made obvious by Hamilton’s use of artist quality titanium white oil paint to help define lines and edges. This paint is much more stable and retains its whiteness better. The titanium white colour used in Hommage à Chrysler Corp. 1957 shows clearly as being still white, whereas the general background colour, which it once matched closely, has changed appreciably.

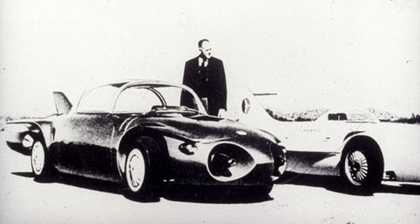

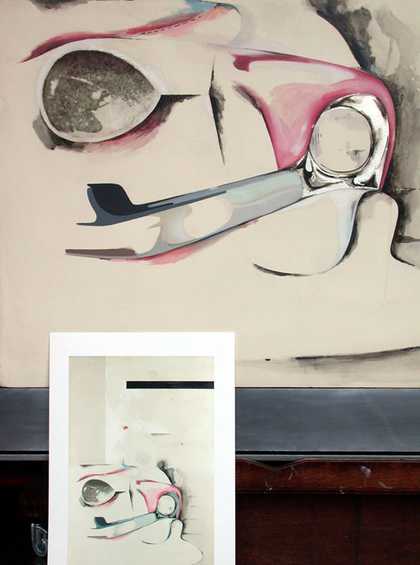

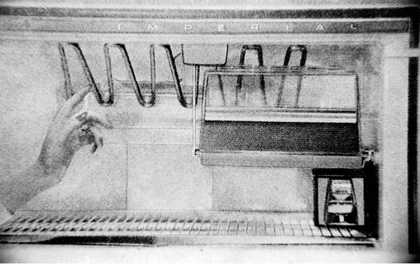

Fig.2 Richard Hamilton, Hommage à Chrysler Corp 1957

Detail of the collage element.

Taken on acquisition, 1995.

Hamilton had come to realise that the undercoat would discolour and stated in 1988: ‘In fact I utilised it. I knew that it was going to change and I sometimes painted white on top of it knowing the titanium white oil paint would be whiter than the background although when I painted it, it might not be very evident.1

What Hamilton found unacceptable, however, were the changes that occurred over time to the collage elements in his work.

The condition of the work on its acquisition by Tate

Before Hommage à Chrysler Corp. 1957 was acquired by Tate, the head of Tate Conservation, Roy Perry, advised the Director and Trustees that the painting’s condition was: ‘consistent with comparable works by Hamilton of the period. The collage element is discoloured, partially detaching and shrunk.2

The image was a response to car advertisements of the 1950s. A woman’s lips seemingly float in isolation above a car until the visual hints of her female form leaning on the bonnet are noted. On the left side, a photographic collage element has been adhered. It might be mistaken for a car headlight if it were not egg-shaped and too high above the bumper. Hamilton enlarged a photograph of a jet-propelled car’s air intake and printed it on thin ‘airmail’ photographic paper. This would have been weak when wet and photographers at Tate suspected residual halides through inadequate washing of the print had caused the fading to develop.

Fig.3 Source for the collage element; a jet engined car

Fig.4 Detail of the jet engined car showing the air-intake

Changes to the collage: discolouration and balance

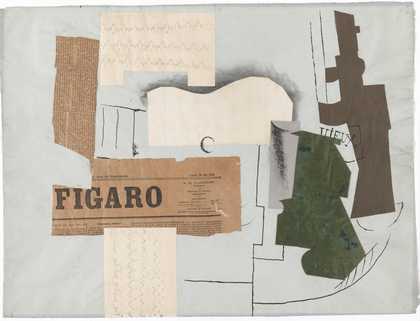

When interviewed in 19883 , in response to the question ‘What is your attitude to the ageing of collage? Is it a change you have to accept as part of the nature of the medium?’ Hamilton replied: ‘It doesn’t worry me. I think Picasso’s cubist collages and newspaper are far more beautiful now than they were because they’ve got this beautiful brown and black colour, that patina which comes with the ageing of paper and print.’

Pablo Picasso

Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (1913)

Tate

However, in October 1996, when Hamilton looked at the painting in Tate Conservation, he was unhappy with the changes the collage element had suffered over time, particularly its loss of intensity through fading of the photographic image. Originally a black and white print, it had generally discoloured to a sepia hue, with the darks and lights becoming more mid tone. As Hamilton had retained the original 35 mm slide from which the photographic element was made, he suggested using it to make a replacement part. He also offered an early black and white negative of the completed painting.

In December 1996 Richard Morphet, then Keeper of the Modern Collection at Tate, discussed the problem with Hamilton in front of the painting. Morphet reported that Hamilton was very anxious that the existing discoloured photograph be replaced by a new one more tonally in keeping with the original balance of the work.4

The edge of the collage element had been painted over by the artist with titanium white oil paint. Looking at the painting in 1996, however, Hamilton was disturbed by the presence of ‘an unintended white penumbra around the form in question’ created by this paint. He hoped something could be done about this too.

Conservation attempt one: a replacement photographic element

Tate made black and white prints from the negative Hamilton supplied showing the early appearance of the painting overall, and an enlargement from the 35 mm slide of the jet engine air intake printed at the required size.

A replacement part was made that illustrated how much the original element had faded in comparison. In 1997 this was shown to Hamilton in the gallery where the painting was hanging. Contemplating the stark black and white replacement print on thick archival paper with the faded original viewed through the low reflecting glass in the display frame convinced Hamilton that a more suitable replacement could be made on a thinner paper, one at least closer to the airmail paper he had originally used. It was agreed there was more to the problem though. Some adjustment would be required to bring the appearance of the replacement collage element into harmony with the altered appearance of the painting generally.5

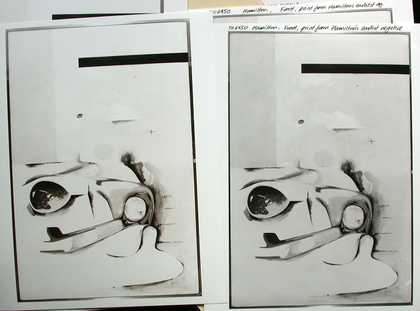

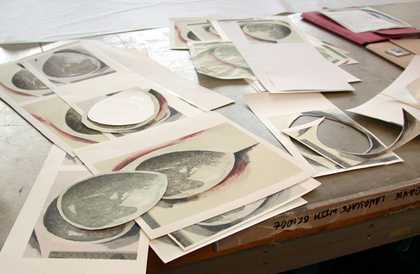

Fig.6 Two of six prints from Hamilton's earliest negative of the painting

Fig.7 The new replacement part held against the original

Conservation attempt two: a digital comparison

Hamilton suggested basing the appearance of the replacement on the existing, faded collage element. A high-resolution digital image of the painting could be adjusted. Hamilton is well acquainted with digital imaging, exploiting this technology frequently in his work. At this time, the National Gallery was engaged on a project capturing high-resolution scans using the ‘methodology for art reproduction in colour’ (MARC) camera (Cuppitt et al. 1996).

It was proposed, therefore, that the painting be sent to the National Gallery for digital scanning. Hamilton could then modify the image file for printing life size, possibly for display alongside the painting at Tate. The purpose would be explained in an accompanying leaflet. Additional examples of Tate paintings where significant change had occurred could be included in a small display.

Hamilton still wanted the collage element replaced but agreed that first assessing the effect digitally could prove useful. It was agreed the National Gallery would be approached to see what might be arranged. Dr David Saunders, conservation scientist at the National Gallery, kindly agreed to capture the digital image with their equipment, a process which eventually happened in November 1997. The image was captured successfully but through a problem with the National Gallery’s large-format printer, the resulting print was too grey to be acceptable.

The ethical concerns of intervention

At Tate, there was concern about removing the original collage element. It was true that lost collaged images of model aeroplane parts in another Hamilton painting had been replaced, but this was not felt to be comparable. If the faded collage element was actually missing, a replacement might well be considered necessary. To remove a piece, however, did not seem ethical. Nevertheless, the artist felt that the faded sepia original compromised the intent of a painting that was about masculine imagery. It was valuable to have the artist’s input to help determine what the appearance of the collage element should be. Certainly, without his encouragement and ultimately his approval, nothing could have been done.

Fig.9 Richard Hamilton, Hommage à Chrysler Corp 1957

Hamilton's manipulated guide print from the National Gallery scan

In 2004 Hamilton supplied his modified print. He had adjusted the colour so the collage element was not truly monochromatic. Instead, it had been given a slight cream cast consistent with the priming layer’s change in colour.

The conservation treatment: a reversible treatment

Given the concerns about removing the original collage element, an idea for carrying out a reversible treatment was explored. Treatment began on 25 May 2004. Following Hamilton’s suggestion, the replacement part would be derived from a photograph of the collage element in its degraded state, but now the aim was to attach the part over the original. Testing the original collage with white spirit and heat at 75 °C had no discernible effect. This indicated reversibility could be achieved using a stable and reversible conservation material, BEVA 371, as the adhesive.

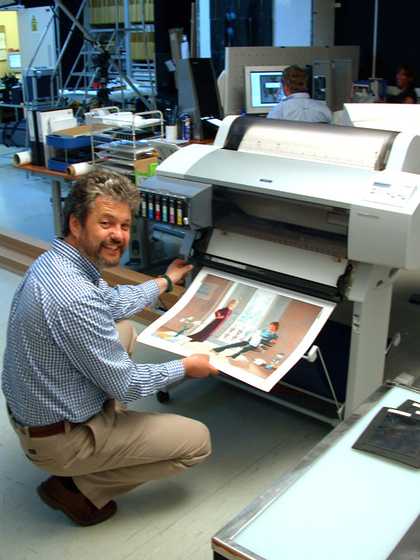

One advantage of the long delay in starting treatment was the technological advances that had been made in digital photography. Permanent pigment inks for inkjet printers had been developed and were now available. Tate’s photography department had purchased an Epson Colour Stylus 7600 Inkjet printer which uses permanent Ultrachrome pigment inks, not fugitive dye-based inks, making durable printing feasible. Digital printing also allowed image manipulation with image editing software so that the image could be adjusted incrementally in a much more controlled way compared to wet process photography. A limiting factor with inkjets, however, is that the appearance of a print varies depending on the paper used and, though manufacturers supply a range of specialist papers, none were sufficiently thin.

Fig.10 David Clarke, Head of Photography, with the Epson 7600 Colour Stylus printer

Fig.11 The roll of cigarette paper in the Paper Conservation Department

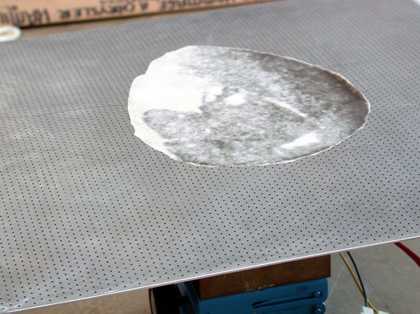

The conservation treatment: printing on thin paper

A visit to Tate’s paper conservation studio revealed a substantial roll of thin cigarette paper in store, a seemingly durable material containing acid-buffering chalk. Indeed, it had already been in their possession for some years and displayed no tell-tale signs of yellowing at the edges. Although chemicals are added during production to modify the combustion of cigarette paper, possibly a concern, the paper would in any event be isolated from the original painting by a layer of adhesive. The familiar closely spaced mock ‘laid lines’ present in cigarette paper were thought too faint to be visible at normal viewing distance. It was necessary to support the thin paper for printing by adhering it with BEVA film to a roll of archival paper.

The first print obtained using the cigarette paper revealed notable shifts in colour and tone: an unacceptable green cast was present in the mid tones and a magenta hue in the darkest areas. Generally, the print looked insipid. Despite compensating for these changes on screen, the corrections did not have the desired effect when printed. The printer had a cartridge of matte black ink but it also mixed primary colours to create black. It appeared that the greater absorbency of the cigarette paper was causing a slight separation of the colours in the mixed black. To put this theory to the test, the absorbency of the paper was reduced by applying sizing or fixing materials. Of several fixatives tested, casein proved the most suitable choice.

Fig.12 Insipid print on cigarette paper, lower part, darker print; on archival paper, top part

Fig.13 The process of printing, adjusting, re-printing again and again produced many prints

The conservation treatment: a suitable replacement image

The deliberations leading to the final selection of the replacement image were lengthy. A key decision was to match its light tones to the titanium white paint around the original collage element. The artist’s guide print was helpful up to a point. Both effects would make the collage element look darker to some unknown degree. Given the imprecision in deciding on the final appearance of the replacement part, it was only the reversibility of the treatment that made continuing with its attachment acceptable.

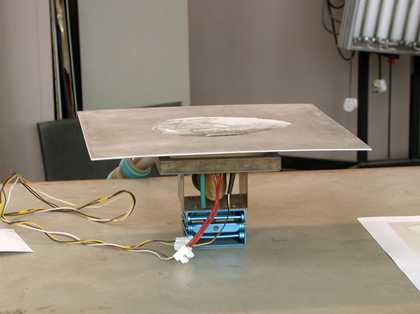

White spirit was applied to free the print from the backing paper required for printing. There was no visible sign that the wax component in the BEVA had impregnated the cigarette paper. BEVA thinned with white spirit was warmed until clear, then several thin coats sprayed onto the reverse using an airbrush. A mini vacuum table with a heating facility was used to hold the replacement part flat and shorten the drying time.

Fig.14 Mini vacuum table

Fig.15 Replacement part drying

Fig.16 Painting after treatment with the artist's guide print

Nothing was done to remove the distortions in the surface of the original collage. Once correctly positioned over the original piece, the replacement part was adhered by heating it to 70°C. The aim had been to apply a minimal amount of BEVA. Finally, pigments bound in Regalrez 1094, a resin used for varnishing paintings, were used to adjust the dark tone of the original collage in a few places where it showed around the edge of the replacement part, and to make several cracks in the titanium white covering the original edge appear less disturbing. The painting was then photographed.

The artist’s reaction to the treatment

On 25 June 2004, while the Tate Britain exhibition Art and the 60s: This Was Tomorrow was being installed, Hamilton viewed the painting hanging in the gallery with a Tate curator. He felt the print was not quite dark enough, but recognised it was a great improvement on the original faded element. Hamilton telephoned Tate on 29 June 2004 to say he was in fact pleased with the result and had not thought of using ink jet printing to make the replacement image. He had previously thought it would have to be a photographic print, but he approved this decision. He then remarked that the appearance of his painting $he 1958–61 was also marred by a discoloured collage element. He hoped it could be treated in the same way.

Fig.17 (Detail) Richard Hamilton, $he 1958–61

Oil, cellulose paint and collage on wood; support: 1219 x 813 mm frame: 1330 x 944 x 98 mm;

painting

© Richard Hamilton 2002. All rights reserved, DACS

Fig.18 (Detail) Richard Hamilton, $he 1958–61

One of many replacement parts for $he produced by Rod Hamilton from a photograph of the original artwork

Further treatment to another Richard Hamilton work

The faded photographic collage element in $he 1958–61 meant that a lot of detail had been lost as well as the paper being discoloured. A different approach was therefore taken. Hamilton still retained the original magazine clipping from which the image had been taken but the ink had bled and faded too much to be used directly. Instead a near contemporary photograph of the artwork was used. It was possible to avoid using a mixed black when printing with the ink jet printer, thereby avoiding the problems with colour matching described above. It was necessary to print a background tone to mimic the yellowed state of the painting overall. The resulting print was not precisely the same dimension as the original. The first attempt to align it was not acceptable and the reversibility of the procedure was therefore tested when the replacement part was taken off, re-positioned and re-adhered.

Fig.19 (Detail) Richard Hamilton, $he 1958–61

An image of the original artwork.

Fig.20 Richard Hamilton, $he 1958–61

Detail view showing the replacement part attached to $he

Contemporary art dilemmas: the role of the artist and the responsibility of the museum

Fig.21 Richard Hamilton, $he 1958–61

Oil, cellulose paint and collage on wood; support: 1219 x 813 mm frame: 1330 x 944 x 98 mm

after treatment

© Richard Hamilton 2002. All rights reserved, DACS

The treatment of Hamilton’s paintings highlights a dilemma about contemporary art. A museum may acquire an object, but the artist retains ownership of the copyright. A critical change in appearance can compromise their original aesthetic intention and in many cases, and quite understandably, the artist would prefer to see this corrected. Sometimes, the extent of change can only be established through discussion with the artist. Indeed, had Hamilton not commented on the unacceptable state of the collage element in Hommage à Chrysler Corp. 1957, the problem might not have been fully realised. It also begs the question: how many other seriously distorted paintings pass unrecognised?

Within a museum, those responsible may be sympathetic to such issues, but are disposed to value the authenticity of the object more highly. Furthermore, each work has its place in history, and later re-working compromises this chronology. However, if a significant improvement would result and treatment is contemplated, the authorisation of the artist is a key requirement. With the treatment of Hommage à Chrysler Corp. 1957 and $he 1958–61, a solution has been found that accommodates these disparate concerns. Unaltered, the artist’s faded original collage elements now lie hidden (but easily uncovered if required) beneath replacements approved by the artist. With this change, the paintings have regained vitality with respect to the treated elements.

This record enables the viewer to find out what has taken place.

References

J. Cupitt, K. Martinez and D. Saunders, ‘A Methodology for Art Reproduction in Colour: the MARC project’, Computers and the History of Art, vol. 6, no. 2, 1996, pp.1-19.

R. Gettens and G.L. Stout, Painting Materials; a Short Encyclopaedia, Dover 1966, pp.7-8.

D. Keynan, ‘Pop Revisited: The Collage and Assemblage Work of Tom Wesselmann’, in Preprints for the IIC Bilbao Congress, 2004, pp.156-9. 472 ICOM Committee for Conservation, 2005, vol.1.