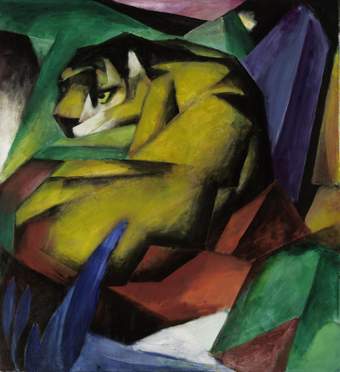

Franz Marc, Tiger, 1912. Lenbachhaus Munich

In our case the principle of internationalism is the only one possible … The whole work, called art, knows no borders or nations, only humanity.

Draft preface to The Blue Rider Almanac, 1911

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Modern

Franz Marc, Tiger, 1912. Lenbachhaus Munich

In our case the principle of internationalism is the only one possible … The whole work, called art, knows no borders or nations, only humanity.

Draft preface to The Blue Rider Almanac, 1911

What comes to mind when you picture expressionism? On the one hand, bold experiments with colour, dramatic forms, atonal music and poetry in free verse. On the other, cross-cultural artistic collaborations set against the imperial ideologies and social inequalities of early 20th century Europe.

Out of this context emerged a unique transnational community of artists known as the Blue Rider. United by the values outlined in their publication The Blue Rider Almanac, they brought together broad and interconnected experiences, relationships and art practices. In this exhibition we spotlight 17 figures – artists, musicians and performers. We meet women artists who defied social conventions as well as those engaging in environmental issues and searching for new forms of spirituality. We also witness how performance enabled some to question seemingly fixed notions of identity and explore cross-cultural connections forged through photography.

The early 1900s was a turbulent age, and the Blue Rider artists experienced wars, revolutions and the dominance of extreme ideologies. Some artists lost their lives, while others were left bereft, stateless, displaced and persecuted. But for a brief moment before the outbreak of the First World War, their experimentation and belief in the transformative power of creativity played a decisive role in the making of European modern art.

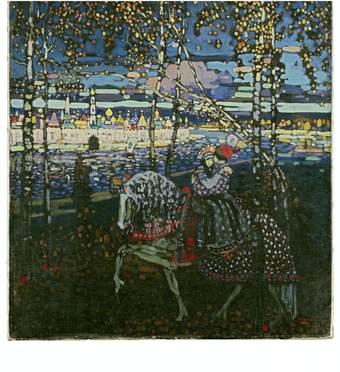

Wassily Kandinsky, Riding Couple 1906-1907, Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957

The exhibition starts with the Blue Rider collective’s core couple, Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter. We then follow like-minded artists from Eastern and Western Europe and the USA as they connect in Munich, engaging in collaborative work. Exploring the key concerns at the heart of their creative experimentation, later rooms are dedicated to spirituality, sonic perception and colour theory. Culminating in the legacies of the Blue Rider artists, this exhibition presents the lasting influence of a transnational artistic collective.

The multicultural identities of the Blue Rider artists as well as their migratory biographies has resulted in various spellings of their names. In this exhibition, we have followed the spellings outlined in the original 1912 edition of The Blue Rider Almanac as well as common spellings of names and places used in the German primary sources of the period.

Elisabeth Epstein, Self-Portrait 1911, Lenbachhaus Munich, on permanent loan from the Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation, Munich

We were only a group of friends who shared a common passion for painting as a form of self-expression. Each of us was interested in the work of the other … in the health and happiness of the others.

Gabriele Münter, 1958

The Blue Rider collective connected artists, musicians and performers across nations, cultures, media and styles. The circle wasn’t constrained by the official status of a group or society. They instead embraced a plurality of creative approaches that came to define modern art in Europe and North America. The collective included women artists and those exploring their gender identities. It grew through a transnational network of contacts and affiliations. This included artists with similar experiences of migration or displacement, as well as those seeking new approaches towards spirituality and artistic expression. Each artist’s complex and varied lived experience contributed to and enriched the collective.

The community’s starting point was the formation of the NKVM (New Artists’ Association of Munich) in 1909. Progressive for its time, the association admitted women artists such as Marianne Werefkin and Elisabeth Epstein, enabling them to exhibit and sell their work. It also drew in musicians such as Thomas von Hartmann and the free movement performer Alexander Sacharoff. Previously solitary figures such as Paul Klee, Franz Marc and Robert Delaunay established creative bonds with other members of the community from 1911 – the year the idea of the Blue Rider was conceived. In this room, you can explore the relationships and affinities that grew between the artists of the Blue Rider circle.

The Blue Rider was a largely Munich-based collective that grew out of personal bonds and connections formed in the early 1900s. It is mainly known for its two experimental exhibitions and The Blue Rider Almanac – a volume of collected images and texts by artists and musicians.

The city of Munich in Bavaria provided a relatively liberal and open environment, attracting marginalised artists from less tolerant societies. This includes artists with Jewish ancestry from Eastern Europe and North America (Epstein, Albert Bloch), creatives from the more conservative Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires (Sacharoff, Erma Bossi), those who didn’t fit socially within their own middle class privileged social group (Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger) or those in pursuit of unconventional romantic partnerships (Werefkin, Alexej Jawlensky). Bavaria enjoyed prosperity, a culturally sophisticated monarchy and a conservative but well-established middle class who supported and sustained artistic experimentation.

At the same time, the artists experienced Bavarian society as it integrated into the German Empire. Founded in 1871, the empire quickly developed into the world's third largest economy. The government pursued imperial and colonial ambitions including the exploitation of people and resources overseas. Public fascination with world cultures was underpinned by racist narratives and cultural and ethnic hierarchies of imperialism. These biases are visible in the display of cultural objects from colonial territories, in particular those collected anonymously and attributed to unknown artists.

Münter’s Tunisian photographs were taken during her and Kandinsky’s trip to North Africa in December 1904–March 1905. During French colonial occupation (1881–1956), Tunisia became a popular tourist destination for Europeans. Following established routes, Münter produced her second largest group of photographic works. Marking the start of a period of active artistic experimentation, she explored new forms of expression using traditional media (painting, embroidery and reverse glass painting) alongside new technologies (photography and linocut prints).

Münter’s architectural imagery demonstrates her interest in depicting the simplified, abstracted essence of a scene. They also reveal her occasional engagement with the established European visual culture of orientalism. This genre of painting and photography tended to depict places and people in North Africa and West Asia in reductive, stereotypical and exoticised terms.

Some images reflect Münter’s broader curiosity and engagement with modern Tunisia as an outsider. She captures a range of scenes including photographs of women in different roles – as mothers, travellers, camel riders and active participants in city life. These photographs counter the orientalist trope of women as odalisques – sexualised depictions of enslaved women. They also reveal the complexities of a colonial capital in a way that doesn’t appear in contemporary orientalist paintings.

Marianne Werefkin, The Dancer, Alexander Sacharoff 1909, Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Museo Comunale d'Arte Moderna, Ascona

Traditionally, theatre and performance offered safe environments for the exploration of sexuality and gender. Performers could switch gender and power roles, and engage with transgressive themes. Artist and patron Werefkin was attracted to the free arts of street theatre and popular entertainment for their freedom of expression and potential to disrupt the highly regulated social structures women were confined to.

Werefkin experimented with expressionist painting while also grappling with questions of identity. This included navigating the legal and social barriers of gender inequality. Her privileged upbringing and financial independence allowed Werefkin to assume a position of power, acting as patron and supporter of the arts – a field traditionally monopolised by men. In this period, such women were given the pejorative label ‘manwoman’ to denote their being ‘unnatural’, members of a ‘third sex’. This perspective was critically explored in the writing of contemporary philosopher and minority rights activist Johannes Holzmann.

Resenting gender binaries, Werefkin stated: ‘I am not a man, I am not a woman, I am I.’ She shared affinities with artists challenging traditional gender roles. This is reflected in her support of performer Sacharoff. Presenting androgynously both on and off stage, Sacharoff explored gender fluidity through new styles of performance that activated form through free movement. Believing that dance resembled music or painting, Sacharoff said: ‘In the art of dance the body must be an elaborate instrument capable of expressing the soul. In this sense, it must be as valid as the word, the sound and the colour’. Performance was central to both Werefkin and Sacharoff’s investigations and constructions of self-identity.

Murnau, a rural town in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps by the shores of the Staffelsee lake, became a place of artistic exchange and inspiration for the Blue Rider artists. Münter and Kandinsky first visited with Werefkin and Jawlensky for a summer open air sketching holiday in 1908. In 1909, Münter purchased a house there, alternating with Kandinsky between the city and the country. Fellow artists Marc and Franck-Marc settled in the neighbouring town of Sindelsdorf and later, Kochel. In 1910, August and Elisabeth Macke moved to nearby Tegernsee. Murnau became a site of creative collaboration that laid the foundations of the NKVM and the Blue Rider. The artists embraced a country lifestyle, swimming in the lake and skiing in the mountains. They also designed their own garden, growing a vegetable patch and using the produce for the household and their guests.

The artists engaged with local arts and crafts, including reverse glass painting. This method consists of painting pictures on the back of a clear glass panel. Viewed from the opposite side of the glass, the colours appear bold and reminiscent of enamels. Münter was the first to learn the technique, later stating that ‘the traditional reverse glass painting which used to flourish around the Staffelsee had a lasting influence on me with its strong colours in black outlines and its carefree decorative designs.’

In Murnau, Kandinsky experimented with the local landscape, simplifying his forms and producing his first non-figurative paintings. Münter forged her own radical approach to figuration ‘intuiting the content, abstracting, presenting the essence’. Werefkin found a spiritual affinity with the environment that fuelled her return to easel painting.

Collecting folk artworks, artefacts and popular media was important for the Blue Rider artists as they strived towards the idea of an art ‘that knows no borders’. They were interested in the local crafts and religious artefacts of Bavarian craftspeople, toys and popular prints from Eastern and Central Europe, as well as prints and reverse glass painting from South and East Asia. Marc and Jawlensky collected Japanese prints. Münter and Franck-Marc were interested in children’s art and toys. Kandinsky collected popular prints and with Münter they assembled religious images to use as motifs in their work. This included votive paintings (commissioned to fulfil a spiritual vow) and carvings of saints and the Madonna. Photographs of their apartment in Munich’s Ainmillestrasse and their house in Murnau showcase their extensive collections.

Objects produced by local and international artists and craftspeople who were not academically trained were perceived by European modernist artists as ‘unspoiled’ and ‘authentic’. When shown in modernist exhibitions and illustrated in publications these works were often presented anonymously and removed from their original context. They were showcased purely for their stylistic qualities, artistry and boldness of colour.

Maria Franck-Marc, Girl with Toddler circa 1913, Lenbachhaus Munich

Art was concerned with the most profound matters, that renewal must not be merely formal but a rebirth of thinking.

Franz Marc, 1914

The Blue Rider circle’s aesthetic concerns developed in parallel with their belief in the deep spiritual significance of artistic experimentation. This drove their creative investigations of form, colour, sound and the performing arts. The artists engaged with diverse structures and systems of belief including pre-Christian tradition and polytheism (belief in more than one deity).

With his background in Christian theology, Marc also became interested in Buddhism. This fuelled his engagement with animism – a belief in the latent spirituality of animals, objects and the natural world. Several artists in the circle followed the emerging controversial esoteric teachings of the Theosophical Society. Theosophists mixed European occult traditions with appropriated elements of Hinduism and Buddhism, ancient Greek philosophy and modern science.

Kandinsky’s 1912 book Concerning the Spiritual in Art communicated a vision for a new, ‘great spiritual’ age, in which all art forms would coalesce. A significant part of this vision rests on the importance of artists’ ‘inner necessity’. This notion described an inherent drive or will towards spiritual expression. Similarly, an interest in the inner creativity and spirituality of children was prominent in scientific and academic research at the turn of the century. This was captured in feminist publications such as Swedish writer Ellen Key’s The Century of the Child, published 1900. This marked a cultural shift that recognised the inner life of children, including their natural spirituality and original creativity. Franck-Marc’s work reveals deep engagement with the subject.

Wassily Kandinsky, Impression III (Concert) 1911, Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957

Kandinsky paints pictures in which the external object is hardly more to him than a stimulus to improvise in colour and form and to express himself as only the composer expressed himself previously.

Arnold Schönberg, 1912

On 2 January 1911, Kandinsky and Marc attended a concert of the experimental composer Arnold Schönberg. Kandinsky’s Impression III (Concert) was created a few days later as a chromatic or visual response. Both creatives strived towards surfacing the connections between colour and sound. Many within the Blue Rider were accomplished or professionally trained musicians. Kandinsky was a skilled cellist and Klee and Feininger were gifted violinists. Schönberg experimented with painting, exhibiting with the collective. His contributions to the Almanac, alongside musicians Thomas von Hartmann and Leonid Sabanejev were central to the group’s questioning of the seemingly rigid boundaries between different creative mediums. Kandinsky experimented with the vital relationship between form and colour, becoming increasingly interested in the neurodivergent condition of synaesthesia. A person with synaesthesia experiences one sense through another, such as perceiving sound through colour.

Kandinsky’s earlier experimentations linked sound, colour and language. He explored this in a book of interlinked free verse and woodcuts entitled Sounds published in 1913. He continued to investigate the connection of drama, words, colour and music through stage performances, one of which was published in the Almanac as ‘Yellow Sound’. Schönberg’s contribution to the Almanac ‘The Relationship to the Text’ explored the abstract nature of poetry as it relates to sound.

This is the first of three experiential rooms in the exhibition. In these rooms, you are invited to explore the Blue Rider’s engagement with sound, colour and light.

The Blue Rider artists’ interest in the relationship between sound and colour was underpinned by scientific investigations. They were particularly engaged with colour theory, a discipline that spanned physics, chemistry, psychology, philosophy and aesthetics. A key inspiration was German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s work on the psychological impact of different colours on mood and emotion, published as Theory of Colours in 1810. The Blue Rider artists pushed these theories further through creative experimentations.

Kandinsky, Marc and others in the group explored the expressive values of colour and form. Marc’s experimentations with light refracting prisms are documented in his correspondence in winter 1911 with August Macke. The correspondence reveals the transition of theoretical thinking into the process of painting: ‘Viewed through a prism, the yellow appeared dull grey, the entire form was surrounded by the most fantastic coloured circles. I now proceed to paint in stages in ‘pure colours’, every time the colour got purer, the colourful circles around the form receded, until finally a clear relation between yellow, the cold white of the snow and the blue emerged’.

The composition of paintings such as Deer in the Snow II testify to this intense exploration of the scientific and emotional qualities of colour. In this room, we invite you to re-enact Marc’s experiments. You can view his painting through an achromatic doublet prism akin to the one used by the artist.

Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation Gorge 1914, Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957

This room brings Kandinsky's work into dialogue with an environmental light installation by contemporary artist Olafur Eliasson. Produced in 2006, Lichtdecke Kandinsky explores the effects of white light in a gallery space. Responding to Kandinsky’s abstract artworks, Eliasson draws attention to the ways in which changing light and colour conditions can affect our perception.

Displayed alongside Eliasson’s installation is Kandinsky’s painting Improvisation Gorge, completed a few months before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Encountering the painting and light installation together might make us think of colour as a concept, or space as an artwork. It also raises questions of authenticity and authorship: how is our perception of the painting affected by Eliasson’s shifting environment?

Blue Rider… will be the call that summons all artists of the new era and rouses the laymen to hear.

Advert for The Blue Rider Almanac, 1911

The collective rallied around their programmatic publication The Blue Rider Almanac. Although only Kandinsky and Marc were credited as co-editors, a collective effort from many artists in the community contributed to the Almanac’s concept, content, design, writing and fundraising, including Münter, Franck-Marc and Elisabeth Macke. This collaborative approach also generated two groundbreaking exhibitions of paintings and works on paper.

The Blue Rider artists navigated the economic and critical landscape of 1900s European artistic circles, successfully building their careers. They participated in exhibitions nationally and internationally as well as staging monographic shows. Collaboration with the gallerist Herwarth Walden ensured access to the art market. They built relationships with museum curators and gallerists while contributing to Walden’s avant-garde magazine Der Sturm, bringing their ideas to a wider audience.

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 the collective dispersed, devastated by the loss of lives and changing personal relationships. Yet, following the Second World War, the Blue Rider works appeared in the first iteration of the Documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany in 1955. This signalled the ongoing relevance of the collective’s dynamic artistic vision. Marking a celebration of complex cultural connections in post-war artistic communities, it also secured the collective’s lasting influence on generations of artists to come.

Sam Smith, Blue Rider Residency, Project Art Works, 2024 (photography by Georgie Scott)

Project Art Works is a collective of neurodiverse artists and activists working from a studio based in Hastings. For this exhibition, Project Art Works artists have created new artworks in response to the colour, form and expression explored in the work of the Blue Rider collective.

Kandinsky released several books of prints, including the self-described ‘musical album’ Klänge (Sounds) in 1913. Here he combined 38 prose poems with 56 experimental woodcuts calling it a ‘small example of synthetic work’. He described the relationships between the texts and illustrations in a letter to his British friend and patron Michael E. Sadler: ‘I wrote them because I could not express these particular feelings as a painter. There is however… a deep inner relationship between the texts and the woodcuts… I treat the word, the sentence in a very similar way to that in which I treat the line, the dot. The great inner relationship of all arts is coming gradually ever more clearly to light.’

Below you can view selected excerpts from the English translation of Klange.