Amedeo Modigliani

Self-Portrait as Pierrot 1915

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Room 1: Open to Change

When Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) decided to leave Italy to develop his career as an artist, there was only one place to go. In 1906, at the age of 21, he moved to Paris.

Many factors shaped his decision. Born in the port city of Livorno, he belonged to an educated Jewish family, who encouraged his ambition and exposed him to languages and literature. He had seen great Renaissance art and had trained as a painter. But Paris offered excitement. Paris offered variety. There he would encounter ways of thinking, seeing and behaving, that challenged and shaped his work.

This exhibition opens with a self-portrait, painted around 1915, in which Modigliani presents himself as the tragic clown Pierrot. His contemporaries would have recognised the reference instantly as, at the time, the figure appeared in countless pictures, plays and films. A young person shaping their identity could relate to Pierrot, a stock character open to interpretation, linked to the past and open to the future. Pierrot could be comedic, melancholy or romantic, played by any actor or painted by any artist. In a new place, among new people, the work signals that Modigliani was ready to invent himself.

Room 2: City Life

Soon after his arrival in Paris, Modigliani began to look at progressive contemporary art. He absorbed the influence of the works he saw, by artists ranging from the recently deceased Paul Cézanne, to his near-contemporary Kees van Dongen. Loose brushwork and bright colours made an appearance as he abandoned a more polished, traditional way of painting. ‘My Italian eyes cannot get used to the light of Paris ... Such an all-embracing light ... You cannot imagine what new themes I have thought up in violet, deep orange and ochre.’

Modigliani lived at various addresses in the bohemian district of Montmartre. Artists including Pablo Picasso lived nearby. He started to exhibit his work and met his first major patron, Paul Alexandre, who bought many drawings and paintings. He also began to paint female nudes, something that would have proved more difficult in conservative Italy, where willing models were harder to come by.

Room 3: Modigliani's Paris

Montmartre had a different character to the rest of Paris. When Modigliani arrived in 1906, it was still known as the ‘village on the hill’, north of the city centre and without its own metro station. Though partly rural – its skyline peppered with windmills – Montmartre’s famous cabarets, theatres and dance venues had earned the neighbourhood a wild reputation. A relatively new attraction – the cinema – became a novel way for Modigliani and his friends (and thousands like them) to spend their evenings. The famous Church of the Sacré-Coeur was still under construction.

In 1909, Modigliani moved to Montparnasse, after the sculptor Constantin Brancusi found him a studio near his own. Serviced by a main train station, the area felt distinctly urban, its wide boulevards accessible by car and important art galleries within walking distance. Fast becoming the centre of the contemporary art scene, Montparnasse attracted artists, writers and poets of all nationalities, who met to while away the hours in cafes such as Le Dôme, La Rotonde and La Closerie des Lilas. For Modigliani, the ramshackle studios of La Ruche (the ‘beehive’), were a home away from home, where he visited artist friends to paint, drink, and sometimes stay the night.

Room 4: Grand Ideas

For a brief but intense period between 1911 and 1913, Modigliani focused almost exclusively on sculpture, making many elegant sculptural drawings. Perhaps these were sketches for sculptures he had in mind – he had plans to create a temple-like structure – although many appear as finished works of art.

Simplification characterises his output from these years. Caryatids were a recurring theme: sculpted, usually female figures who, with raised arms, could also serve as architectural supports.

Visits to Paris museums, including the Louvre and the ethnography museum at the Trocadéro (across the river from the 22-year-old Eiffel Tower), inspired Modigliani and countless other European artists to look at Egyptian, Khmer, African and early Italian art. The experience led them to value simplicity of line, and to prioritise a frontal viewpoint, though their use of these references was liberal.

Paul Guillaume, Modigliani’s art dealer from 1914, was one of the few Europeans at the time to treat African statues and masks as works of art. A selfmade man, still in his early twenties, Guillaume also impressed Modigliani by supporting contemporary art in Paris. Portraits show him sharply dressed and confident.

Room 5: Modigliani the Sculptor

Many who knew Modigliani recalled his early commitment to being a sculptor. His patron Paul Alexandre recalled how the artist worked around 1911–12: ‘When a figure haunted his mind, he would draw feverishly with unbelievable speed, never retouching, starting the same drawing ten times in an evening by the light of a candle … He sculpted the same way. He drew for a long time, then he attacked the block directly.’

Modigliani’s sculptures found an audience. Several of the Heads displayed here belonged to a group of seven sculptures that featured in an important annual art exhibition, the Salon d’Automne, held from October to November in 1912. It was the only significant display of Modigliani’s sculpture held during his lifetime. Already troubled by the after-effects of childhood tuberculosis, dust from carving may have aggravated his breathing.

In the Salon, the sculptures became part of a room that exhibited cubist paintings, a placement which Modigliani may have anticipated when he referred to them as a ‘decorative ensemble’. But he would abandon sculpture soon after. It was considerably more expensive than painting, even if several contemporary accounts suggest that Modigliani ‘found’ his limestone from local building sites.

He could also better explore his developing style in two-dimensions. Elongated faces with stylised features, swan-like necks and blank, almond-shaped eyes would soon appear in his paintings.

Room 6: Creative networks

In a series of expressive portraits, Modigliani captured fellow artists from Montmartre and Montparnasse. Most worked in the radical new style of cubism, flattening space in their paintings abstracting the faces of their models. Appropriately, when Modigliani painted Spanish painter Juan Gris and Parisian artist Henri Laurens, he gave them angular profiles and stylised features. Although Modigliani experimented with cubism, he never rejected figurative representation, even if he remained impressed by Picasso. ‘Picasso is always ten years ahead of us’, he said, inscribing his portrait with the word ‘SAVOIR’ or ‘knowing’.

Alliances formed regardless of nationality. A wealthy Franco-American painter, Frank Burty Haviland, helped his contemporaries by buying their works. Russian sculptor Léon Indenbaum shared a studio with Modigliani and sat for a portrait. ‘He glanced at me at brief intervals and as he painted he hardly moved. His brush, held upwards like a bow, played out to perfection his wondrous vision … At the end of the third sitting he signed this real masterpiece and held it out to me. ‘It’s for you,’ he said.’

Room 7: Kindred Spirits

A decade after moving to Paris, Modigliani had made the city his own. He was a well-known figure in Montparnasse’s close-knit artistic community and counted artists, poets, actors, musicians and writers among his friends. He captured their colourful personalities while experimenting with mark-making techniques

and lettering. In some cases he even wrote a sitter’s name across the canvas.

Modigliani made several paintings of the poet Beatrice Hastings. Lovers from 1914–15, their volatile romance was marked by drunken arguments and substance abuse, though it was a source of creative energy for both. Yet as much as Modigliani was part of this vibrant international community, in other ways, he was an outsider. Ever committed to portraiture – at a time when it was relatively unfashionable – he did not gain vocal support from the critics with whom he socialised. And as a Jew in France, where anti-Semitism was commonplace, he would have faced prejudice.

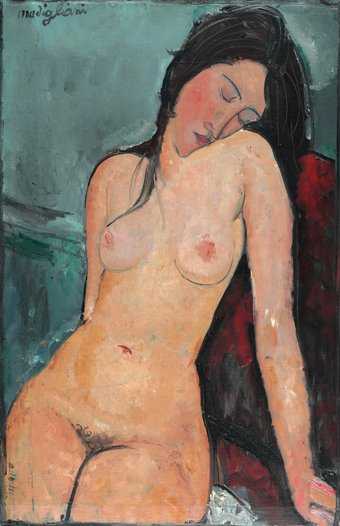

Room 8: Modern Nudes

Thanks to the support of a new art dealer, Léopold Zborowski, in 1916 Modigliani returned to painting the female nude. His professional models earned five francs per sitting, around twice the daily wage of a female factory worker during the First World War, and comparable to the daily 15 franc stipend that Modigliani received from his dealer.

If Modigliani made these paintings for male buyers, their sensuality suggests changes in the lives of young women, who were increasingly independent in the 1910s. The models dominate the compositions, often making eye contact with the viewer, their made-up faces hinting at the growing influence of female film stars.

At the time, these modern nudes proved shocking. In 1917, when some of the paintings were included in Modigliani’s only lifetime solo exhibition, a police commissioner asked for their removal on the grounds of indecency. He found their pubic hair offensive. Traditionally, in fine art, nudes were hair-free.

Room 9: Heading South

Amedeo Modigliani

The Little Peasant c.1918

© Tate

In the last months of the First World War, with Paris suffering air raids and with Modigliani’s health growing worse, Zborowski decided to send his artist to the French Riviera. Modigliani was anxious about the move: ‘All these changes, changes of circumstance and the change of the season, make me fear for a change of rhythm and atmosphere.’ However, given the number of his city friends who had also headed south, he would still find plenty of company. Even his new partner, the painter Jeanne Hébuterne was there, together with her mother as a chaperone. By this stage she was pregnant with the couple’s first child.

Modigliani made some of his strongest works in Nice. He worked quickly, as one of his sitters, Germaine Meyer, recalled: ‘The portrait was finished after a few hours without him stopping even for a minute.’ In the absence of professional models, he painted local children and his friends, capturing them in warm Mediterranean colours.

Room 10: Modigliani VR Experience: The Ochre Atelier

Modigliani VR: The Ochre Atelier

Courtesy of Preloaded

In 1919 Modigliani returned to Paris from the south of France. The war was over; his health had improved. Zborowski found a studio and living space for Modigliani and Hébuterne on the rue de la Grand Chaumière, near the cafes and meeting places of Montparnasse. Modigliani’s friend Lunia Czechowska recalled: ’This was a very modest kingdom, but it was his. I’ll never forget the day when he took possession of his new domain. His happiness was enough to move us all.’

Modigliani’s final studio still exists, but almost 100 years after the artist’s death, its appearance has changed significantly. Through study of documentary material and of Modigliani’s works themselves, the environment in which the artist made his last works is reimagined. In this room you can immerse yourself in a virtual reality recreation of Modigliani’s final studio, which uses the actual studio space as a template.

Room 11: An Intimate Circle

Though Modigliani knew many people, a few characters appear repeatedly in his artworks. These people – his closest contacts – were also his most convenient models. Zborowski and his partner Anna Sierzpowski (known as Hanka Zborowska) feature often, smartly dressed, firmly middle-class in appearance.

Jeanne Hébuterne was Modigliani’s most regular sitter. They lived together; she was the mother of their child and the two were engaged to be married The paintings show her in different guises, from a girlish figure with her hair tied back, to a self-assured pregnant woman. If Modigliani had by now found a distinctive way of working, in subtle ways, he continued to experiment. The treatment of Hébuterne’s features varies greatly in the works gathered here.

In the grip of addiction, with his health ever weaker, Modigliani died in January 1920 at the age of 35. Hébuterne – expecting their second child – took her own life a few days later. However, in a remarkable late self-portrait, the artist captured himself as a confident professional, loaded palette in hand.

Virtual reality in partnership with HTC VIVE