Art under Attack is the first exhibition exploring the history of physical attacks on art in Britain from the 16th century to the present day. Visitors will not only be able to see the level of damage that has been done to works of art for religious, political and aesthetic reasons, but can also examine the motivations for these assaults, through objects, paintings, sculpture and archival material.

Tabitha Barber, co-curator of the exhibition, says:

When putting the exhibition together, we wanted to find out what it is that compels people to carry out attacks on art and whether these motives have changed over the course of 500 years. To help visitors understand more about the topic, we’ve divided the exhibition into three parts: religion, politics and aesthetics. The section on religion looks at the 16th and 17th centuries, including the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII, the Reformation and Puritan iconoclasm in the Civil War. Meanwhile, our approach to political iconoclasm has been to focus on attacks on public sculpture: we actually have fragments of a statue of George III that once stood in New York, which was pulled down after the reading of the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

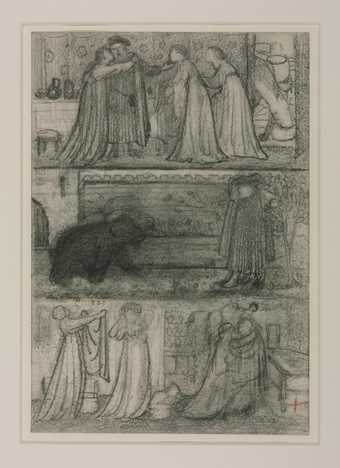

Visitors will learn how the Suffragette campaign became more militant and turned from window-smashing to attacks on art. Paintings in public museums were attacked in order to effect political change. Gallery directors discussed proposals to ban women from their institutions, introduced plain-clothes policemen and circulated surveillance photographs of known militants; women were asked to leave muffs, bags and umbrellas at the entrance.

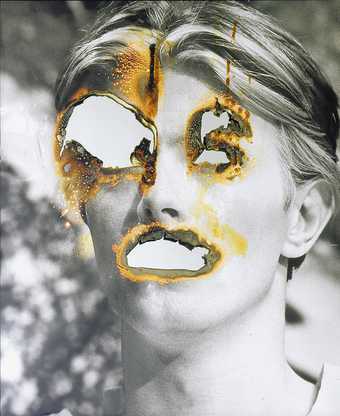

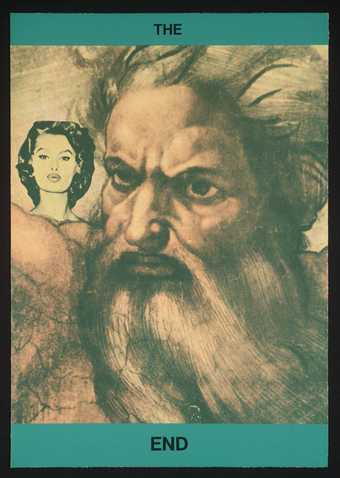

The exhibition moves on to look at contemporary works of art which have been attacked, such as the famous ‘Tate Bricks’ (Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII) which had food dye thrown over it, and artists who choose to use destruction in their art as a creative force.

A number of pieces in the exhibition have never been displayed in the public realm before, including the Statue of the Dead Christ (c.1500–20), which is widely recognised as one of the most important examples of sculpture to survive the violent destruction of religious reformers in the 16th century. The piece was discovered in 1954 and it’s a graphic portrayal of Christ removed from the cross: the crown of thorns, arms and lower legs missing, probably at the hands of Protestant iconoclasts.

A marvellously wide-ranging and witty new exhibition

New StatesmanA fascinating exploration of physical attacks on paintings and sculptures

The Observer