Mark Titchner is fascinated by the myriad systems of belief that permeate contemporary culture. He often revisits defunct and outmoded philosophies, especially those born out of an avant-garde idealism which has long since waned. Conflicting theories are extracted from their historical framework and submitted to us for reappraisal, reassembled as hybrid installations incorporating wall paintings, vinyl banners, light boxes and hand-carved sculptures.

Whether combining song lyrics with the writings of the twentieth-century German philosopher Martin Heidegger or remaking 1960s scientific devices out of hardware store materials, Titchner’s interest lies in the dissolution of boundaries, the migration of ideas and aesthetics from one discipline to another. His recent series of wall paintings constructed from airbrushed geometric shapes was initially based on his memories of the 1970s wallpaper he grew up with. He sees a trajectory originating from patterns in early abstract art, such as paintings by Kasimir Malevich or Joseph Albers, through to the homogenised patterns present in home décor, from high art to high street. A shared aesthetic persists without the conceptual or spiritual dimension that was fundamental to its origination. It is an examination of this cultural filtering process – the survival and popularisation of certain elements over and above others – which lies at the core of Titchner’s practice.

In his installation BE ANGRY BUT DON’T STOP BREATHING, Titchner situates the gallery between the experimental forum of the laboratory and the devotional space of the cathedral. Through sculptural and text-based works, he conflates the philosophies of four cult figures whose theories were planted firmly outside scientific orthodoxy: Wilheim Reich MD, Marxist psychoanalyst and pioneer of Orgone energy; Arthur Janov, pioneer of Primal Therapy; Hans Jenny, natural scientist and inventor of Cymatics and Emmanuel Swedenborg, philosopher and theologian.

The central component of Titchner’s installation is a laboriously hand-carved contraption, the latest in an ongoing series of semi-functional works that explores notions of ritual and devotion. Visitors are invited to shout into one of the six arms protruding from its hexagonal base and watch as their collective screams, with the help of electronic amplification, become manifest as vibrations in an adjacent tray of liquid. This totemistic sculpture parodies a number of dissonant ideas. Jenny’s theory of Cymatics, the idea that all matter in the universe vibrates and therefore through its study we can gain a more complete understanding of existence, is combined with Primal Scream Therapy, a popular misreading of the natural therapy pioneered by Janov in the late 1960s that linked the repression of mental pain with physical breakdown. A third strand is presented through the introduction of Swedenborg’s proposition that the original communication was a pure expression of divinity from which language was subsequently generated. This further abstracts the procedure into an investigation into the true nature of the word. The sculpture therefore functions as a multi-faceted experimental mechanism, the language of logic applied to an illogical interweaving of theories, which relies on the viewer for activation.

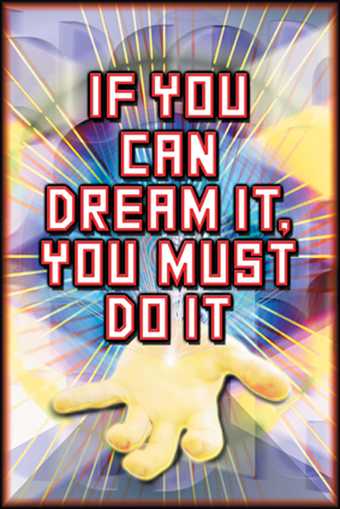

Titchner links disparate elements of the installation through the repetition of the hexagon, the graphic symbol for benzene which is a key solvent used in organic chemistry. This motif is further disseminated through the number six. The six vertical freestanding banners surrounding the sculpture echo in scale and form the religious standards common to churches and cathedrals (a swallow-tailed silk flag suspended from a pole). At the centre of each a hand-carved wooden plaque is inscribed with a single word introduced by the word ‘and’, suggesting an infinite accumulation of information. Contrasting with the roughly hewn surface of the sculpture and acting as a sort of altarpiece for the space, a huge digitally printed banner confidently asserts BE ANGRY BUT DON’T STOP BREATHING. Its typeface is reminiscent of early computer graphics and is offset by a digitally generated starburst that is an attempt to suggest spiritual redemption and deliverance.

The phrase is taken from the poster for WR: Mysteries of the Organism, the controversial 1971 film by Dusan Makavejev loosely based on the life and work of Wilheim Reich. Found text features largely in Titchner’s practice, eclectic phrases pilfered from miscellaneous sources and transformed into philosophical proclamations that seemingly demand a response. However, an ambiguity surrounds the tone of the delivery of these phrases as they are presented, devoid of context, as slick graphic posters or lightboxes with the vapidity of mainstream advertising. It is unclear whether we are to interpret them with sincerity, cynicism or humour. Titchner sees these proclamations as a sort of ‘cod-philosophy, scavenged from the collapsed space that used to keep disciplines like philosophy and pop music apart’1 .

Titchner does not appear to offer judgement or critique of the theories he appropriates. Rather, he provides a secular reinterpretation, maintaining a freedom to mix and overlay ideas. He exploits the catchphrases and clichés that bubble to the surface while dispensing with the theoretical frameworks from which they emerged. Through this process, he simultaneously highlights the redundancy of once radical thought whilst acknowledging the potential for certain aspects to seep quietly into popular consciousness. By amalgamating ideologies, Titchner persuades us to accept the validity of opposing beliefs, underlining both the susceptibility and complexity of the collective psyche.

Text by Lizzie Carey-Thomas